William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

A Brief History of Birmingham

Anglo-Saxon Birmingham

AD 449 - 1066

Little is known about the Anglo-Saxon invasion; whether the area was taken over by large numbers of new settlers or whether new lords simply took over existing patterns of social organisation is

not known. Angles appear to have come from the east and Saxons from the south. Very little archaeological evidence survives; placename evidence, however, is plentiful. Occupation here was

generally not based on villages but on scattered farmsteads especially in the forested area. By the time of the Norman Conquest the population had reached perhaps 1¼ million.

After the departure of the last two legions of the Roman army 410 AD Britain was attacked by tribes initially intent on looting and pillage, later with the intention of invasion, conquest and

settlement. Under the Roman Empire in the 3rd century Saxon mercenaries had been paid to settle in Britain and to defend the east coast against Picts and Scots and other hostile invaders. The

traditional story tells of the British king, Vortigern who in 449 AD asked Hengest and Horsa, two Saxon brothers to come from Germany to help defend Britain. This they did but they also brought

with them their relations and friends. The invasion of Britain by Anglo-Saxons had begun by invitation. It seems that Vortigern failed to pay his armed defenders who wreaked bloody revenge and

took land in lieu of payment.

The coming of the Anglo-Saxons is sometimes known by the Latin term Adventus meaning 'arrival'. Whatever the truth of the legend, the earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had been established

in the south-east by 450 AD. In most of England the Celtic language culture was rapidly replaced by that of the Anglo-Saxons.

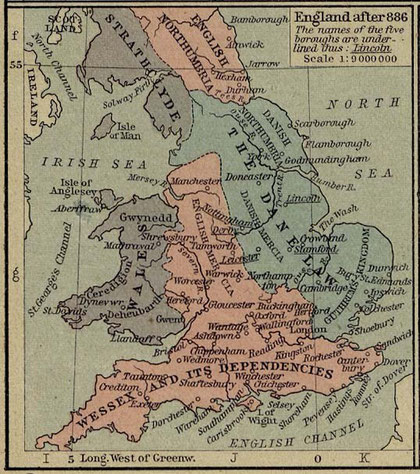

Birmingham lies on the borderland of the territory of the Angles and the Saxons. Anglian people had settled the Midlands from the east following the valleys of the Rivers Trent and Tame. Pagan

burials in Anglian style excavated at Baginton near Coventry have been dated as early as 500. The kingdom of Mercia was founded by Anglians c585, and by the 7th century stretched south of the

River Humber and west of the River Trent to the west Midlands with its capital was at Tamworth. Mercia expanded under King Penda and by the 8th century Offa ruled all of England south of the

Humber between Wales and East Anglia. His coins proclaimed him Rex Anglorum, Latin for 'King of the English'. In 873 Mercia fell to the Danes.

Anglians may have settled first along the Birmingham sandstone ridge which runs from Bromsgrove to Lichfield, or on the pebble lands to the west of it. There may have been thin woodland of birch

and hazel here or the land may have been cleared by earlier peoples and reverted to light cover of gorse, broom and heather. Although not especially fertile and poor at retaining water, the land

would have been fairly easy to clear and plough. Anglian settlements in this area may have been (north to south) Sutton, Erdington, Witton, Aston, Nechells, Birmingham, Edgbaston, Harborne and

Weoley. Towards the end of the Anglo-Saxon period Anglian territory in Birmingham became parts of Staffordshire and Warwickshire.

The Celts of modern Gloucestershire, Hereford and Worcester held out longest against the Saxons but suffered final defeat at the hands of the West Saxons at the Battle of Dyrham in

Gloucestershire in 577. This allowed a West Saxon people known as the Hwicce (pronounced Whichee) to move northwards up the Rivers Severn and Avon and to establish the Hwiccan kingdom with its

capital at Worcester. Archaeological evidence suggests sparse Saxon settlement and it is likely that the population here was predominantly Celtic. The Hwicce were conquered by c628 probably by

the Mercian king, Penda and the kingdom subsequently administered as a separate unit under the aegis of Mercia.

Covering much of the clay lands of the south and east of the Birmingham area was the Forest of Arden which stretched down towards Stratford-upon-Avon. The extent of clearance and agricultural use

by the Celts at the end of the Roman period is not known. However, the earliest Hwiccan Saxons would have farmed first on sites where glacial gravel drifts on top of the sticky clay made clearing

and ploughing easier. Early Saxon settlements on clay lands are on patches of drift: Acocks Green, Greet, Kings Norton, Lea Village, Moseley, Northfield, Selly, Tyseley, Yardley for example.

Slowly would they have begun to expand into the more difficult clay lands to make new settlements. Saxon territory in Birmingham was later to become part of Worcestershire.

By the time of the Norman Conquest of 1066 there were many hamlets, tiny villages scattered round the Birmingham area. Birmingham was one of the poorer manors with probably less than fifty

inhabitants. There were few plough teams and few mills in the area. As the population grew during the 10th and 11th centuries new settlements were founded as offshoots of the original village.

Newer settlements were often on heavier clay soil and had woodland to be cleared.

The name of Birmingham derives from Beorma-ing-ham which translates from the Old English as 'Beorma's people's village'. These people may have been followers of a man called Beorma (pronounced

Berma) but were, more likely, a tribe or clan called the Beormings, 'Beorma's people'. They were an Anglian people moving southwards following the River Trent and then the Tame to settle the

lighter soils of the Birmingham ridge. It is possible that a leader called Beorma founded a settlement here, but equally likely that it was founded by a people named after him. The city's name is

probably best interpreted as 'the village of the Beormings'.

The name developed in two different ways which are reflected in early spellings. Until the widespread use of the printing press, spelling was a very inconsistent. But it did represent the way

people's pronunciation. From the following list of 'Birmingham' spellings it may be seen that the first element of the name is equally shown as Brum as it is with Birm. The name evolved into both

as Birmingham and Brummagem. It is still a matter of debate why the one finally took took precedence over the other.

A local historian, William Hamper compiled a list of spellings of Birmingham from contemporary documents which he published in 1880:

1086 Birmingeha; 1189 Brumingeham;

1200 Brimingham; 1214 Birminggeham; 1221 Burmingeham; 1227 Birmingham; 1227 Byrmyngham;

1235 Burmingham; 1245 Bermincham; 1247 Bermigham; 1248 Bermingham; 1256 Bremingeham;

1260 Burmincham; 1262 Burmigham; 1262 Burmungeham; 1285 Bernigeham; 1282 Byrmychiham;

1292 Birmyngham; 1292 Burmegham; 1297 Burmynchham; 1297 Bermygham;

1317 Burmicham; 1320 Birmyncham; 1320 Byrmincham; 1326 Bermyncham; 1330 Birmincham;

1332 Burmyncham; 1354 Burmincheham; 1337 Brimygham; 1377 Brymygham; 1387 Burmyngham;

1398 Bremyngeham;

1402 Brymecham; 1421 Birmyncham; 1421 Birmicham; 1424 Brymmyngham; 1438 Burmyngeham;

1440 Byrmyncham; 1457 Byrmycham; 1460 Brymygeham; 1469 Brymycham; 1476 Birmyngeham;

1486 Brimyncham; 1489 Birmycham;

1500 Brymyngham; 1504 Bromechham; 1506 Brymyscham; 1514 Brymingham; 1519 Brymmncham;

1520 Bormycham; 1520 Brymyngiam; 1522 Bremygiam; 1529 Bremycham; 1535 Bermegam;

1535 Brymmyngeham; 1537 Bremmycham; 1537 Brymedgham; 1538 Bromycheham; 1548 Bremyngham;

1549 Brymyncham; 1550 Burmycheham; 1553 Brimincham; 1573 Breemejam; 1576 Bromwicham;

1586 Bryngham; 1590 Brymicham; 1591 Bromecham; 1591 Brymigham;

1603 Bermicham; 1603 Bromicham; 1650 Bromegem; 1675 Bromwichham; 1679 Bromwicham;

1686 Brymmyngiam.

It has sometimes been suggested that the village grew up at the crossing of the River Rea between Digbeth and Deritend. The crossing of a river might make a good place for trade. However, this

was a low-lying site that was always prone to flooding until the river was culverted at the beginning of the last century. It is not a likely spot for a settlement. It has also long been assumed

that the original Anglo-Saxon settlement was around the Bull Ring. From medieval times roads from the west converged on the Bull Ring bringing traders from Lichfield, Stafford, Wolverhampton,

Dudley, Halesowen and Worcester, and from the east travellers from Coleshill, Coventry, Warwick and Stratford, and Alcester.

Excavations in advance of the new Bull Ring shopping centre found evidence of a farm of the Roman period on the south side of Park Street on the site of Selfridge's car park. There was also ample

medieval evidence: traces of boundary banks and ditches, houses, cattle and a variety of industries.

However, there was no sign of the Anglo-Saxons. Lack of evidence does not, of course, disprove an Anglo-Saxon village here. Such evidence would anyway be scant as it is across the whole city. However, it does raise the possibility that the first settlement may have been elsewhere.

A site in Hockley has been suggested which certainly would have been more central to the manor. In 1783 William Hutton recorded a moated site here, the residence of Sir Thomas de Birmingham.

Although Sir Thomas had inherited the manor in 1390 from his brother John, he could not gain the manor house until John's widow died. So he built himself a 'castle' at 'Warstone near the

Sandpits'. It was surrounded by a square moat typical of that date, but it is possible that the site is earlier. Alternatively, a site on Easy Hill between the top of New Street and the beginning

of Broad Street is also a possibility.

A recent suggestion is that the Parsonage Moat represents the original Anglo-Saxon manor house. This was a circular moated site and therefore likely to be 12th-century; four-sided moats are

usually of the 13th or the 14th century. Standing near the junction of Edgbaston Street and Pershore Street, the moated site may have subsequently become the home farm of the new manor house,

until it was rebuilt as the parsonage of St Martins-in-the Bull Ring. The moat was filled with water until the mid-18th century. The Parsonage was demolished in the 1820s and the moat was filled

in. The site has now been redeveloped as part of the new Bull Ring Markets.

William Dargue 18.04.09