William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

The Birmingham Riots 1791

The Church & King Riots/ The Priestley Riots

Calendar of the Birmingham Riots

Friday 14 July 1791, Bastille Day in the Republic of France, saw the beginning of Birmingham Riots, also known as the Priestley or Church & King Riots. The spark that exploded the keg was a dinner held at Dadley’s Hotel in Temple Row in the town centre. A number of gentlemen met here to celebrate the 2nd anniversary of the French Revolution; they were members of a wealthy and non-conformist/ dissenting elite who were dominant in Birmingham, entrepreneurs, industrialists and free-thinkers.

The rioters were traditional Birmingham working men, whose cry was “Church & King”, ironically people of a similar class to those who were instrumental in overthrowing the established order in France. However, it is certain that they were provoked to riot by the influence of members of the Anglican and royalist establishment in the town who feared for themselves and their way of life should an English Revolution ever take place. And at that time, it was by no means uncertain.

For three days gangs attacked the homes of wealthy non-conformist families in and around Birmingham.

Thursday 14 July 1791

3-6 pm: A dinner was held on Bastille Day for 80 supporters of the 1789 French Revolution at Dadleys Hotel, Temple Row. Many of the diners were prominent Birmingham dissenters. Although careful to propose their first toast to Church & King, their names had been published in the local newspaper.

8 pm: Although the diners had departed, a drunken mob of anti-dissenters gathered outside the hotel breaking windows shouting ‘Church & King for ever!’

Some rioters burnt down the New Meeting House in New Meeting Street where Joseph Priestley was the minister. This was later rebuilt as a Unitarian chapel in 1802 which is now St Michael & St Joseph’s RC Church.

The Old Meeting in Philip Street/ Old Meeting Street (roughly the New Street Station forecourt area off Smallbrook Queensway) was also wrecked.

Then the rioters went down Digbeth, up Camp Hill and into the countryside along the Stratford Road to the house of the scientist and dissenting minister, Joseph Priestley at Fair Hill, now Priestley Road, Sparkbrook. Priestley’s wine was drunk and his food eaten, his belongings were stolen, his scientific work destroyed and his house burnt. Priestley subsequently left for New York in 1794 never to return to this country.

Friday 15 July 1791

2 pm: Just outside the town 1000 rioters burnt down John Ryland’s Baskerville House on Easy Hill, Broad Street, formerly John Baskerville’s residence. Some drunken rioters burned with it. Several hundred special constables who had been hastily sworn in by magistrates in St Philip’s churchyard were repulsed by the mob.

Other rioters burnt John Taylor’s Bordesley Hall; William Hutton could see the smole from his home in Washwood Heath.

On the High Street (opposite the junction with New Street) William Hutton’s shop and town house were destroyed including his entire stock of paper and books.

Saturday 16 July 1791

In Peck Lane (now beneath the central part of New Street Station) the town prison in Peck Lane was broken open and the inmates were released.

Meanwhile on Washwood Heath Road William Hutton’s country house, Red Hill was burned.

George Humphrey’s home was Sparkbrook House on the Stratford Road (at Gladstone Road). He had a furniture warehouse here. Although he killed one of the mob with a pistol shot, he was forced to leave and his house was ransacked, though not totally destroyed.

On Balsall Heath, presumably on the Moseley Road, Presbyterian minister, Rev John Hobson’s private boys’ school for 8 dissenting boarders was burned down.

The mob followed the Moseley Road to Moseley Hall. Owned by John Taylor, this was the residence of the elderly dowager Lady Carhampton who was frail and blind. She was allowed to leave with a few belongings after which the mob burned the house down.

And then on to Kings Heath House, now in Kings Heath Park, where John Harwood’s house was also burned.

On Wake Green Road (between St Agnes Road and Billesley Lane) was Thomas Hawkes’ Wake Green House, Joseph Priestley had made his escape from Fair Hill and stayed here. However, his stay was short-lived as this house too was wrecked.

Priestley also sought refuge at William Russells’ Showell Green House on nearby Showell Green Lane. The family had departed for Warstock the previous day, while William stayed with his servants to repel the mob. However, as the gangs of rioters approached Russell’s men saw to their own safety and left. The house was looted and burned down.

Sunday 17 July 1791

The Russells left for the home of one of their old servants, Mrs Cox whose family lived at Warstock some five miles away. They believed they would be safe from the Birmingham rioters at Cox’s Farm (not identified, but quite possibly Warstock Farm off Warstock Lane, now Shorters Avenue and Crest View). However, the rioters soon arrived to eat the fod and drink the beer in the cellars before setting fire to the farm buildings.

The Russells took refuge with a neighbouring tenant at Mr Taverner's house, which was also subsequently destroyed.

Ranting, roaring, drinking, burning, is a life of too much rapidity for the human frame to support. Our black sovereigns had now held it nearly three days and nights, when nature called for rest; and the bright morning displayed the fields, roads, and hedges, lined with 'friends and brother Church-men', dead drunk! There were, however, enough awake to kindle new fires. On Sunday the 17th they bent their course to Wharstock, a single house, inhabited by Mr. Cox, and licensed for public worship, which, after emptying the cellar, they burnt.

from The life of William Hutton including a particular account of the riots at Birmingham in 1791; to which is subjoined, the history of his family written by himself and published by his daughter, Catherine Hutton, published 1816

And then on another mile to Kingswood, 7 miles now from Birmingham where Kingswood Meeting House and manse were burnt along with six houses in Kings Norton.

Other houses partially damaged were

Ladywood House at the junction of Monument Road and Wood Road, the home of Harry Hunt (St John’s Church was built on this site in 1854);

Near Five Ways, Edgbaston, the home of Rev Coates;

Hay Hall at Hay Mills, the home of Joseph Smith.

Dr William Withering’s Edgbaston Hall was saved by the arrival that evening of 64 men of the 15th Regiment of Dragoons who had been force-marched from Nottingham. The troops were welcomed by thousands of people in the town and peace was quickly restored.

However, the troops were billeted in pubs and private houses in the town much to the annoyance of the residents. Permanent Barracks for some 150 men and their horses were built the following year in Ashted on 2ha between Great Brooke Street and Windsor Street as a result of the riots. The barracks survived until the 1930s when the area was redeveloped for council housing as the Ashcroft estate.

William Hutton's Narrative of the Birmingham Riots 1791

A Narrative Of The Riots In Birmingham, July 14, 1791,

Particularly As They Affected The Author.

William Hutton/ Catherine Hutton August 1791

The fatal 14th of July was now arrived, a day that will mark Birmingham with disgrace for ages to come. The laws had lost their protection, every security of the inhabitants was given up, the black fiends of hell were whistled together and let loose for unmerited destruction. She has reason to keep that anniversary in sackcloth and ashes. About eighty persons of various denominations dined together at the hotel. During dinner, which was short, perhaps from three to five o'clock, the infant mob, collected under the auspices of a few in elevated life, began with hooting, crying 'Church and King,' and broke the hotel windows.

As Mr. Chillingworth walked by the hotel early in the afternoon of the 14th, twenty or thirty people were assembled, all quiet: he heard one of the town-beadles say to another, 'This will be such a day as we never saw.' 'Why so?' says Chillingworth. After repeated inquiries, one of them replied, 'the gentlemen will not suffer this treatment from the Presbyterians; they will be put on no longer.' The beadles could not make this remark without having heard hostile expressions fall from the gentlemen, which proves a preconcerted plan.

It was now between eight and nine; the numbers of the mob were increased, their spirits were inflamed. Dr. Priestley was sought for, but he had not dined at the hotel. The magistrates, who had dined at the Swan, a neighbouring tavern, by way of counterbalance, huzzaed Church and King, waving their hats, which inspired fresh vigour into the mob, so that they verily thought, and often declared, they acted with the approbation at least of the higher powers, and that what they did was right. The windows of the hotel being broken, a gentleman said, 'You have done mischief enough here, go to the Meetings.' A simple remark, and almost without precise meaning, but it involved a dreadful combination of ideas. There was no need to say, 'Go and burn the Meetings.' The mob marched down Bull Street under the smiles of magistrates. It has been said that these were compelled to echo the cry of the multitude, but it is not wholly true. While the insurgents were intoxicated with liquor and power, and carried vengeance where they pleased, it was necessary to say as they said, and many persons damned the Presbyterians who were their real friends; but till the New Meeting was condemned, this was far from being the case; every smile, word, or huzza encouraged them. Had the same wish existed to repress, as did to raise them, no mischief had ensued.

The New Meeting was broken open without ceremony, the pews, cushions, books, and pulpit were dashed to pieces, and in half an hour the whole was in a blaze, while the savage multitude rejoiced at the view.

The Old Meeting was the next mark of the mob. This underwent the fate of the New: and here again a system seems to have been adopted, for the engines were suffered to play upon the adjoining houses to prevent their taking fire, but not upon the Meeting House, which was levelled with the ground.

The mob then undertook a march of more than a mile, to the house of Dr. Priestley, which was plundered and burnt without mercy, the Doctor and his family barely escaping. Exclusive of the furniture, a very large and valuable library was destroyed, the collection of a long and assiduous life.

But the greatest loss that Dr. Priestley sustained was in the destruction of his philosophical apparatus, and his remarks. These can never be replaced. I am inclined to think he would not have destroyed his apparatus and manuscripts for any sum of money that could have been offered him. His love to man was great, his usefulness greater. I have been informed by the faculty that his experimental discoveries on air, applied to medical purposes, have preserved the lives of thousands; and, in return, he can scarcely preserve his own.

A clergyman attended this outrage, and was charged with examining and even pocketing the manuscripts. I think he paid the doctor a compliment, by showing a regard for his works, I will farther do him the justice to believe he never meant to keep them, to invade the Doctor's profession by turning philosopher, or to sell them, though valuable; but only to exchange them with the minister for preferment. There may be fortitude in dying for treason, but there is more profit in getting a living by it.

Breaking the windows of this hotel, burning the two Meeting Houses, and Dr. Priestley's, finished the dreadful work of Thursday night. To all this I was a perfect stranger, for I had left the town early in the evening, and slept in the country.

When I arose the next morning, July 15, my servant told me what had happened. I was inclined to believe it only a report: but coming to the town, I found it a melancholy truth, and matters wore an unfavourable aspect, for one mob cannot continue long inactive, and there were two or three floating up and down, seeking whom they might devour, though I was not under the least apprehension of danger to myself. The affrighted inhabitants came in bodies to ask my opinion. As the danger admitted of no delay, I gave this short answer - 'Apply to the magistrates, and request four things: to swear in as many constables as are willing, and arm them; to apply to the commanding officer of the recruiting parties for his assistance; to apply to Lord Beauchamp to call out the militia in the neighbourhood; and to write to the Secretary at War for a military force.' What became of my four hints in uncertain, but the result proved they were lost.

Towards noon a body of near a thousand attacked the mansion of my friend, John Ryland, Esq., at Easy Hill. He was not at the dinner. Every room was entered with eagerness; but the cellar, in which were wines to the amount of 300l., with ferocity. Here they regaled till the roof fell in with the flames, and six or seven lost their lives. I was surprised at this rude attack, for I considered Mr. Ryland as a friend to the whole human race. He had done more public business than any other within my knowledge, and not only without a reward, but without a fault. I thought an obelisk ought rather to have been raised to his own honour, than his house burnt down to the disgrace of others.

About this time a person approached me in tears, and told me 'my house was condemned to fall.' As I had never with design offended any man, nor heard any allegations against my conduct, I could not credit the information. Being no man's enemy, I could not believe I had an enemy myself. I thought the people, who had known me forty years, esteemed me too much to injure me. But I drew from fair premises false conclusions. My fellow-sufferers had been guilty of one fault, but I of two. I was not only a dissenter, but an active Commissioner in the Court of Requests. With regard to the first my sentiments were never rigid. There seems to me as much reason to allow for a difference of opinion as of face. Nature never designed to make two things alike. Whoever will take the trouble to read my works will neither find a persecuting, disloyal, or republican thought. In the office of Commissioner I studied the good of others, not my own. Three points I ever kept in view;: to keep order, do justice tempered with lenity, and compose differences, Armed with power, I have put a period to thousands of quarrels, have softened the rugged tempers of devouring antagonists, and, without expense to themselves, sent them away friends. But the fatal rock upon which I split was, I never could find a way to let both parties win. If ninety-nine were content, and one was not, that one would be more solicitous to injure me than the ninety-nine to serve me.

It never appeared when the military force was sent for, but I believe about noon this day. The express, however, did not arrive in London till the next, at two in the afternoon. What could occasion this insufferable neglect, or why the Riot Act was omitted to be read sooner, I leave to the Magistrates. Many solicitations were made to the magistrates for assistance to quell the mob, but the answer was, 'Pacific measures are adopted.' Captain Archibald, and Lieutenants Smith and Maxwell, of recruiting parties, offered their service; still the same answer. A gentleman asked if he might arm his dependents? 'The hazard will be yours.' Again, whether he might carry a brace of pistols in his own defence? 'If you kill a man you must be responsible.'

About noon also some of my friends advised me 'to take care of my goods, for my house must come down.' I treated the advice as ridiculous, and replied, 'That was their duty, and the duty of every inhabitant, for my case was theirs; I had only the power of an individual. Besides, fifty waggons could not have carried off my stock in trade, exclusive of the furniture of my house; and if they could, where must I deposit it?' I sent, however, a small quantity of paper to a neighbour, who returned it, and the whole afterwards fell a prey to rapine.

All business was now at a stand. The shops were shut. The town prison and that of the Court of Requests were thrown open, and their strength was added to that of their deliverers. Some gentlemen advised the insurgents assembled in New Street to disperse; when one, whom I well knew, said, 'Do not disperse, they want to sell us. If you will pull down Hutton's house I will give you two guineas to drink, for it was owing to him I lost a cause in the Court.' The bargain was instantly struck, and my building fell.

About three o'clock they approached me. I expostulated with them. 'They would have money.' I gave them all I had, even to a single halfpenny, which one of them had the meanness to take. They wanted more, 'nor would they submit to this treatment,' and began to break the windows, and attempted the goods. I then borrowed all I instantly could, which I gave them, and shook a hundred hard and black hands. 'We will have some drink.' 'You shall have what you please if you will not injure me.' I was then seized by the collar on both sides, and hauled a prisoner to a neighbouring public-house, where, in half an hour, I found an ale-score against me of 329 gallons.

The affrighted magistrates were now sitting at the Swan in Bull Street, swearing constables, whom they ordered to rendezvous in St. Philip's Churchyard, 'where they would meet them.' Here the new-created officers, armed with small sticks, waited with impatience, but no magistrates came. They then bent their course without a leader, to New Street, attacked the mob which had been with me most furiously, and in a minute dispersed it. As my house was in the utmost danger, they ought to have stayed to protect it, instead of which they went to guard Mr. Ryland's, nearly burnt down. Here the mob came upon them with double force, took their weapons, totally routed them, maimed several, and killed Mr. Thomas Ashwin.

My son wishing to secure our premises, purchased the favour of Rice, one of the leaders, who promised to preserve his person and property, and assured him that his men would implicitly obey him. Hearing Mr. Taylor's house was in danger, they marched to Bordesley, one mile, to save it, but found another mob had begun to rob and burn it. I could assign no more reason why they attempted Mr. Taylor's property than Mr. Ryland's. No man could cultivate peace and social harmony more. His is the art of doing good by stealth. Offence was never charged against him; but alas, he was a Dissenter. The sons of plunder, and their abettors, forgot that the prosperity of Birmingham was owing to a dissenter, father to the man whose property they were destroying. He not only supplied thousands of that class who were burning his son's house with the means of bread, but taught their directors the roads to invention, industry, commerce, and affluence; roads which no man trod before him. Nay, when the Meeting Houses were fallen, and the Church was falling, even this violent outrage itself was quelled by the vigilence of a Dissenter, Captain Polhill.

Rice and my son, being too late to render any essential service to Mr. Taylor's premises, returned to save our own. But meeting in Digbeth some of our furniture, Rice declared it was too late; that he could have kept off the mob, but could not bring them off. Perhaps the instant view of plunder had changed his sentiments. Meeting a rogue near the Swan with a bundle of paper worth 5l., Rice damned him, and ordered him to lay it down. The rogue instantly obeyed. Rice sat upon it, while my son requested a neighbour to take it in, who refused. He then applied to a second, but received the same answer, and was obliged to leave Rice and the paper to secure his own person.

Rice then joined the depredators in destroying my house and its contents, and the next morning was one of the leaders in burning my house at Bennet's Hill. These facts were proved against him on his trial by the clearest evidence, and yet an alibi was admitted from one who swore he was then drinking a pot of ale with a soldier at a public-house; but, had he sworn he was drinking with the man in the moon, the oath would have been freely admitted.

About five this evening, Friday, I had retreated to my house at Bennet's Hill, where, about three hours before, I had left my afflicted wife and daughter, and had seen a mob at Mr. Jukes's house in my road. I found that my people had applied to a neighbour to secure some of our furniture, who refused; to a second, who consented; but another shrewdly remarking that he would run a hazard of having his own house burnt, a denial was the consequence. A third request was made, but cut short with a No. The fourth man consented, and we emptied the house into his house and barn. Before night, however, he caught the terror of the neighbourhood, and ordered the principal part of the furniture back, and we were obliged to obey.

At midnight I could see from my house the flames of Bordesley hall rise with dreadful aspect. I learned that after I quitted Birmingham the mob had attacked my house there three times. My son bought them off repeatedly; but in the fourth, which began about nine at night, they laboured till eight the next morning, when they had so completely ravaged my dwelling, that I write this narrative in a house without furniture, without roof, door, chimney-piece, window, or window-frame. During this interval of eleven hours, a lighted candle was brought four times, with intent to fire the house, but, by some humane foot, it was kicked out. At my return I found a large heap of shavings, chips, and faggots, covered with about three hundredweight of coal in an under kitchen, ready for lighting.

The different pieces of furniture were hoisted to the upper windows to complete their destruction; and those pieces which survived the fall, were dashed to atoms by three bludgeoners stationed below for that service. Flushed with this triumphant exercise of lawless power, the words, 'Down with the Court of Conscience!' 'No more ale scores to be paid,' were repeated. A gentleman remarked to the grand slaughterers of my goods, 'You'll be hanged, as the rioters were in 1780.' 'O, damn him,' was the reply, 'he made me pay fifteen shillings in the Court of conscience.' This remark was probably true, for that diabolical character which could employ itself in such base work, was very likely to cheat another of fifteen shillings, and I just as likely to prevent him.

Burning Mr. Ryland's house at Easy Hill, Mr. Taylor's at Bordesley, and the destruction of mine at Birmingham, were the work of Friday the 15th.

Saturday the 16th was ushered in with fresh calamities to myself. The triumphant mob, at four in the morning, attacked my premises at Bennet's Hill, and threw out the furniture I had tried to save. It was consumed in three fires, the marks of which remain, and the house expired in one vast blaze. The women were as alert as the men. One female, who had stolen some of the property, carried it home while the house was in flames; but returning, saw the coach-house and stables unhurt, and exclaimed, with the decisive tone of an Amazon, 'Damn the coach-house, is not that down yet? We will not do our work by halves!' she instantly brought a lighted faggot from the building, set fire to the coach-house, and reduced the whole to ashes.

The beautiful and costly mansion of George Humphrys, Esq., was the next victim. He had prepared for a vigorous defence, and would most certainly have been victorious, for he had none but rank cowards to contend with, but female fears overbalanced manly courage. One pistol, charged with powder, sent them away; and though they returned in greater numbers, one blunderbuss would have banished them for ever. His house was sacked, and the internal parts destroyed.

The next sacrifice was the house of William Russell, Esq., at Showell Green. He had prepared men, arms, ammunition, and a determined resolution for defence; but, finding his auxiliaries rotten, he gave up his house and its contents to the flames.

The house of Thomas Russell, Esq., and that of Mr. Hawkes, at Moseley-Wake Green, were the next attacked. They were plundered and greatly injured, but not burnt. To be a Dissenter was a crime not to be forgiven, but a rich Dissenter merited the extreme of vengeance.

Moseley Hall, the property of John Taylor, Esq., and inhabited by Lady Carhampton, mother to the Duchess of Cumberland, was not to be missed. Neither the years of this lady, being blind with age, nor her alliance to the Crown, were able to protect it. She was ordered by the mob to remover her furniture, and told, if she wanted help, they would assist her; but that the mansion must not stand. She was therefore, like Lot, hastened away before the flames arose, but not by angels.

As riches could not save a man, neither could poverty. The mob next fell upon a poor, but sensible Presbyterian parson, the Rev. John Hobson, of Balsall Heath, and burnt his all.

From the house of Mr. Hobson, the intoxicated crew proceeded to that of William Piddock, at King's Heath, inhabited by an inoffensive blind man, John Harwood, a Baptist; and this ended their work on Saturday the 16th, in which were destroyed eight houses, exclusive of Mr. Coates's, which was plundered and damaged.

Some of the nobility, justices, and gentlemen arrived this day, sat in council, drank their wine, harangued the mobs wished them to desist, told them what mischief they had done, which they already knew; and that they had done enough, which they did not believe; but not one word of fire-arms, a fatal proof that pacific measures were adopted. To tell a mob 'They have done enough,' supposes that something ought to have been done. A clear ratification of part at least of their proceedings.

On this day some curious advertisements appeared. I shall insert one or two for the dastardly spirit they exhibit; another for its singular composition.

'Birmingham, July 16, 1791.

'FRIENDS AND FELLOW COUNTRYMEN, - It is earnestly requested that every true friend to the Church of England, and to the laws of his country, will reflect how much a continuance of the present proceedings must injure that church and that King they are intended to support, and how highly unlawful it is to destroy the rights and property of any of our neighbours. And all true friends to the town and trade of Birmingham, in particular, are intreated to forbear immediately from all riotous and violent proceedings, dispersing and returning peaceably to their callings, as the only way to do credit to themselves and their cause, and to promote the peace, happiness, and prosperity of this great and flourishing town.'

'Birmingham, Sunday, July 17, 1791.

'Important Information to the friends of Church and King.

'FRIENDS AND BROTHER CHURCHMEN, - Being convinced you are unacquainted that the great losses which are sustained by your burning and destroying of the houses of so many individuals will eventually fall upon the county at large, and not upon the persons to whom they belonged, we feel it our duty to inform you that the damage already done, upon the best calculation that can be made, will amount to upwards of One Hundred Thousand Pounds! The whole of which enormous sum will be charged upon the respective parishes, and paid out of the rates. We therefore, as your friends, conjure you immediately to desist from the destruction of any more houses, otherwise the very proceedings of your zeal for showing your attachment to your church and King will eventually be the means of most seriously injuring innumerable families, who are hearty supporters of government, and bring on an addition of taxes, which yourselves and the rest of the friends of the Church will feel a very grievous burthen.

'This we assure you was the case in London, when there were so many houses and public buildings burnt and destroyed in the year 1780, and you may rely upon it will be the case on the present occasion.

'And we must observe to you that any farther violent proceedings will more offend your King and country than serve the cause of him and the Church.

'Fellow Countrymen, as you love your King, regard his Law, and Restore Peace.

'GOD SAVE THE KING.'

Inquiries were made every moment, 'When will the military arrive to defend us?' but not one thought occurred of defending ourselves. Such is the infatuation of the mind, and such the consequence when mobs are masters.

With regard to myself, I felt more resentment than fear; and would most willingly have made one, even of a small number, to arm and face them. My family, however, would not suffer me to stay in Birmingham, and I was, on Saturday morning, the 16th, obliged to run away like a thief, and hide myself from the world. I had injured no man, and yet durst not face man. I had spent a life in distributing justice to others, and now wanted it myself. However fond of home, and whatever were my comforts there, I was obliged, with my family, to throw myself upon the world without money in my pocket.

We stopped at Sutton Coldfield, and as we had no abode, took apartments for the summer. Here I fell into company with a clergyman, a lawyer, a country squire, and two other persons, who all lamented the proceedings at Birmingham, perhaps through fear, they being in its vicinity, and blamed Dr. Priestley as the cause. I asked what he had done? 'He has written such letters! Besides, what shameful healths were drank at the hotel.' As I was not at the dinner, I could not speak of the healths; but I replied, 'If the Doctor, or any one else, had broken the laws of his country, those laws were open to punish him, but the present mode of revenge was detested even by savages.' We left our argument, as arguments are usually left by disputants, where we found it.

I asked the people at the Castle Inn whether they knew me. They answered in the negative. I had now a most painful task to undergo. 'Though I have entered your house,' said I, 'as a common guest, I am a desolate wanderer, without money to pay or property to pledge.' The man who had paid his bills during sixty-eight years must have been sensibly touched to make this declaration. If he had feelings, it would call them forth. Their countenance fell on hearing it. I farther told them I was known to Mr Robert Bage, a gentleman of the neighbourhood, whom I would request to pay my bill. My credit rose in proportion to the value of the name mentioned. Myself, my wife, son, and daughter passed the night at the Castle at Tamworth. We now entered upon Sunday, the 17th. I rose early, not from sleep, but from bed. The lively sky and bright sun seemed to rejoice the whole creation, and dispel every gloom but mine. I could see through the eye of every face that serenity of mind which I had lost.

As the storm in Birmingham was too violent to last, it seemed prudent to be near the place, that I might embrace the first opportunity of protecting the wreck of a shattered fortune. We moved to Castle Bromwich.

Ranting, roaring, drinking, burning, is a life of too much rapidity for the human frame to support. Our black sovereigns had now held it nearly three days and nights, when nature called for rest; and the bright morning displayed the fields, roads, and hedges, lined with friends and brother Churchmen dead drunk. There were, however, enough awake to kindle new fires. On Sunday, the 17th, they bent their course to Wharstock, a single house, inhabited by Mr. Cox, and licensed for public worship, which, after emptying the cellar, they burnt.

Penetrating one mile farther, they arrived at Kingswood Meeting House, which they laid in ashes. This solitary place had fallen by the hand of violence in the beginning of George the First, for which a person of the name of Dollax was executed, and from him it acquired the name of St. Dollax, which it still bears. He was the first person who suffered after passing the Riot Act.

Three hundred yards beyond, they arrived at the parsonage-house, which underwent the same fate.

Perhaps they found the parish of King's Norton too barren to support a mob in affluence; for they returned towards Birmingham, which, though dreadfully sacked, yet was better furnished with money, strong liquors, and various other property. King's Norton is an extensive manor belonging to the king, whose name they were advancing upon the walls, whose honour they were augmenting by burning three places of worship in his manor, and by destroying nine houses, the property of his peaceable tenants.

The Wedensbury colliers now assembled in a body, and marched into Birmingham to join their brethren under Church and King; but, finding no mob in the town, they durst not venture upon an attack, but retreated in disappointment. As they could not, however, return with a safe conscience without mischief, they attacked Mr. Male's house, at Belle Vue, six miles from the town; but he, with that spirit which ought to have animated us, beat them off. While I was hidden at Castle Bromwich, a gentleman sent up his compliments and requested admission. We appeared personal strangers. He expressed a sorrow for my misfortunes, and observed, in the course of our conversation, 'that as I was obliged to leave home abruptly, and had uncertainty before me, perhaps I was not supplied with a sufficiency of cash; that he was returning from a journey, and had not much left, but that what he and his servant had was at my service, and tomorrow he would send him with whatever sum I should name.' Surprised at so singular a kindness, which I could neither merit nor expect, I requested the name of the person to whom I was indebted for so benevolent an act. He replied, 'John Finch, banker, of Dudley.' Those generous traits of character fictitiously ascribed to heroes of romance were realized in this gentleman. With sorrow I read in the public papers, in December following, the death of this worthy man, whom I never saw before or after. I could not refrain from going to take a view of my house at Bennet's Hill, above three miles distant from Castle Bromwich. Upon Washwood Heath I met four waggons, loaded with Lady Carhampton's furniture, attended by a body of rioters, with their usual arms, as protectors. I passed through the midst of them, was known, and insulted, but kept a sullen silence. The stupid dunces vociferated, 'No popery! Down with the pope!' forgetting that Presbyterians were never remarkable for favouring the religion of that potentate. In this instance, however, they were ignorantly right; for I consider myself a true friend to the roman catholic, and to every peaceable profession, but not to the spiritual power of any; for this, instead of humanizing the mind, and drawing the affections of one man towards another, has bound the world in fetters, and set at variance those who were friends.

I saw the ruins yet burning of that once-happy spot, which had for many years been my calm retreat - the scene of contemplation, of domestic felicity - the source of health and contentment. Here I had consulted the dead, and attempted to amuse the living. Here I had exchanged the world for my little family.

Perhaps fifty people were enjoying themselves upon those ruins where I had possessed an exclusive right, but I was now viewed as an intruder. The prejudiced vulgar, who never inquire into causes and effects, or the true state of things, fix the idea of criminality upon the man who is borne down by the crowd, and every foot is elevated to kick him. My premises, laid open by ferocious authority, were free to every trespasser, and I was the only person who did not rejoice in the ruins. It was not possible to retreat from that favourite place without a gloom upon the mind, which was the result of ill-treatment by power without right. This excited a contempt of the world.

Returning to Castle Bromwich, the same rioters were at the door of the inn, and I durst not enter. Thus the man who, for misconduct, merited the halter, could face the world; and I, who had not offended, was obliged to skulk behind hedges. Night came on. The inhabitants of the village surrounded me, and seemed alarmed. They told me it was dangerous to stay among them, and advised me, for my own safety, to retreat to Stonnal. Thus I found it as difficult to procure an asylum for myself as, two days before, I had done for my goods. I was avoided as a pestilence; the waves of sorrow rolled over me, and beat me down with multiplied force; every one came heavier than the last. My children were distressed. My wife, through long affliction, ready to quit my own arms for those of death; and I myself reduced to the sad necessity of humbly begging a draught of water at a cottage! What a reverse of situation! How thin the barriers between affluence and poverty! By the smiles of the inhabitants of Birmingham I acquired a fortune; by an astonishing defect in our police I lost it. In the morning of the 15th I was a rich man; in the evening I was ruined. At ten at night on the 17th I might have been found leaning on a mile-stone upon Sutton Coldfield, without food, without home, without money, and, what is the last resort of the wretched, without hope. What had I done to merit this severe calamity? Why did not I stay at home, oppose the villains at my own door, and sell my life at the dearest rate? I could have destroyed several before I had fallen myself. This may be counted rash; but unmerited distress like mine could operate but two ways - a man must either sink under it or become desperate.

While surrounded by the gloom of night, and the still greater gloom which oppressed the mind, a person seemed to hover about me who had evidently some design. Whether an honest man or a knave gave me no concern; for I had nothing to lose but life, which I esteemed of little value. He approached nearer with seeming diffidence, 'Sir, is not your name Hutton?' 'Yes.' 'I have good news. The light-horse, some time ago, passed through Sutton, in their way to Birmingham.' As I had been treated with nine falsehoods for one truth, I asked his authority. He replied, 'I saw them.' This arrival I knew would put a period to plunder. The inhabitants of Birmingham received them with open arms, with illuminations, and viewed them as their deliverers.

We left the mob towards evening on Sunday the 17th returning from King's Norton. They cast a glance upon the well-stored cellar, and valuable plunder, of Edgbaston Hall, the residence of Dr. Withering, who perhaps never heard a Presbyterian sermon, and yet is as amiable a character as he who has. Before their work was completed, the words lighthorse sounded in their ears; when this formidable banditti mouldered away, no soul knew how, and not a shadow of it could be found.

Exclusive of the devastations above-mentioned, the rabble did numberless mischiefs. The lower class among us, long inured to fire, had now treated themselves with a full regale of their favourite element. If their teachers are faithful to their trust, they will present to their idea another powerful flame in reversion.

Next morning, Monday the 18th, I returned to Birmingham to be treated with the sad spectacle of another house in ruins. Every part of the mutilated building declared that the hand of violence had been there.

My friends received me with joy; and though they had not fought for me, they had been assiduous in securing some of my property, which, I was told, 'had paved half the streets in Birmingham.'

Seventeen of my friends offered me their own houses; sixteen of them were of the Established Church, which indicates that I never was a party man. Our cabinets being rifled, papers against Government were eagerly sought after; but the invidious seeker forgot that such papers are not in use among the Dissenters. Instead, however, of finding treasonable papers I mine, they found one of my teeth wrapped in writing paper, and inscribed 'This tooth was destroyed by a tough crust July 12, 1775, after a faithful service of more than fifty years. I have only thirty-one left.' The prize was proclaimed the former property of a king, and was conducted into the London papers, in which the world was told, 'that the antiquaries had sustained an irreparable injury; for one of the sufferers in the late riots had lost a tooth of Richard the Third, found in Bosworth Field, and valued at 300l.'

Some of the rioters absconded. A thousand might have been taken if taking had been the fashion, but the taker had every obstacle to encounter. As their crimes glared in the strong light of the sun, or rather the fire, the actors were generally known, and the proofs full. Fifteen were committed. Their trials were a mere farce, a joke upon justice and truly laughable. It is a common remark, that 'a man will catch at a twig to save his life;' but here the culprit had no need to seek for a twig, he might be saved by a straw, a thread, or even by the string of a spider. Every assistance was thrown out, and every one was able to bring a rioter out of danger.

The Solicitor of the Treasury was sent from London to conduct the trials of the rioters. He treated me with civility, and said, 'If Mr. Ryland and I would go to his lodgings at Warwick next Sunday morning at ten, he would show us a list of the jury, and we should select twelve names to our satisfaction.' I thanked him, and took the journey accordingly. Upon perusing the list, I was surprised to find they had but ONE sentiment. I returned the paper with an air of disappointment. 'They are all of a sort,' said I, 'you may take which you please.' At that moment John Brooke, the true blue church and King's man, and the attorney employed against the sufferers, entered, and as silently as if he had listened behind the door. He had, no doubt, fabricated the list. We instantly retreated.

Rice's case has been mentioned. Another was saved, because he went to serve the sufferer. Whenever the offender procured a character, and one may be picked up in every street, he was sure to be safe. The common crier rang his bell while Mr. Ryland's house was in flames, to call on the mob; but at the trial 'he did it to call them off.' Another was charged with 'pulling down and destroying,' but as the house was afterwards burnt, it was wisely inferred 'he could neither pull down nor destroy that which was burnt.'

It was proved against Hands, 'that he tore up Mr. Ryland's floor and burnt it;' but he got clear by another attesting that there was no floor. Careless stole the pigs, which every one believed, but he was acquitted by his sister swearing that 'he drove them out to save them.' Watkins escaped, because the evidence could not tell the number of the rioters. Four witnesses, perfectly clear and consistent, accused Whitehead, but he was acquitted by the evidence of one only, James Mould, who denied all they had said, and observed, 'that Whitehead did all he could to save my property.' The real fact was, I hired Mould, with nine others to guard my house at Bennett's Hill, on Friday night. When the riots were over, he was the man who informed against Whitehead as a ringleader, described his person, name, trade, and place of abode; consequently was the sole cause of his being taken. If, however, he swore him into danger, he was allowed to swear him out. How the Court looked, and how the jury felt when facts were set aside, and oaths and characters too their place, I leave to those who were present to decide. . . .Three criminals were executed; Cook for destroying the house of Mr. Russell; Field for that of Mr. Taylor; and Green for Dr. Priestley's. Mr. Russell would have solicited a pardon for Cook, but found his character so notoriously bad, that there was no ground for his plea. Those of Field and Green are better known to others than myself; they were represented as infernals let loose among men. The world will be apt to draw this conclusion, None were executed for the riots.

Although the public are in possession of the toasts drunk at the hotel, I shall subjoin them, that the people both in and out of Sutton may judge how far they were shameful. The company, out of respect to monarchy, had procured from an ingenious artist three figures, which were placed upon the table. One, a fine medallion of the king, encircled with glory, on his right an emblematical figure, representing British Liberty; on the left, another representing Gallic Slavery breaking its chains. These innocent and loyal devices were ruinous; for a spy, whom I well know, was sent into the room, and assured the people without, 'that the Revolutionists had cut off the king's head, and placed it on the table.' Thus a man with a keen belief, like one with a keen appetite, is able to swallow the grossest absurdities.

1. The King and Constitution.

2. The National Assembly and Patriots of France, whose virtue and wisdom have raised twenty-six millions from the meanest condition of despotism, to the dignity and happiness of freemen.

3. The majesty of the People.

4. May the Constitution of France be rendered perfect and perpetual.

5. May Great Britain, France, and Ireland unite in perpetual friendship; and may their only rivalship be the extension of peace and liberty, wisdom and virtue.

6. The rights of man. May all nations have the wisdom to understand, and courage to assert and defend them.

7. The true friends of the Constitution of this country, who wish to preserve its spirit by correcting its abuses.

8. May the people of England never cease to remonstrate till their parliament becomes a true national representation.

9. The Prince of Wales.

10. The United States of America; may they for ever enjoy the liberty which they so honourably acquired.

11. May the revolution in Poland prove the harbinger of a more perfect system of liberty extending to that great kingdom.

12. May the nations of Europe become so enlightened as never more to be deluded into savage wars by the ambition of their rulers.13. May the sword never be unsheathed but for the defence and liberty of our country; and then, may every one cast away the scabbard till the people are safe and free.

14. To the glorious memory of Hampden, Sidney, and other heroes of all ages and nations, who have fought and bled for liberty.

15. To the memory of Dr. Price, and all those illustrious sages who have enlightened mankind in the true principles of civil society.16. Peace and goodwill to all mankind.17. Prosperity to the town of Birmingham.

18. A happy meeting to the friends of liberty on the 14th of July, 1792.

The sum total of the above toasts amounts to this, a solicitude for the perfect freedom of man, arising from a love to the species. If I were required to explain the words freedom and liberty in their full extent, I should answer in these simple words, that each individual think and act as he please, provided no other is injured.

We have now taken a concise view of the rise and progress of a species of punishment inflicted on innocence, which would have been insufferable for the greatest enormities; and with a tear I record the sorrowful thought that there appeared afterwards no more repentance on one side than there had been faults on the other.

End of the narrative of the riots of July, 1791.

Written in August that year.

The Riots at Birmingham, July 1791 - a Pamphlet

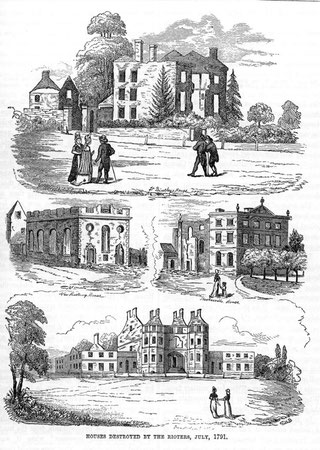

For the images above, see the descriptions at the bottom of this page.

PREFACE

The present work consists of an exact Reprint of a Pamphlet published shortly after the Riots; also of Witton’s Views of the Ruins, with their accompanying descriptions. The Views have been transferred to stone, (by Mr. FREDERICK GREW, of Birmingham,) from the original mezzotint plates, which are still preserved; and for the free use of which the Publisher is indebted to H.W. TYNDALL, ESQ.

The following additional particulars may perhaps be interesting.

OLD MEETING HOUSE – This, most likely, was the first Dissenting place of worship erected in Birmingham. The congregation probably dates as far back as the Act of Uniformity; but, being illegal, their devotions had to be performed in secret, and we have no record of them until 1672, when, in consequence of an indulgence, they were allowed to have a licensed room, - the situation of which is now, however, unknown. The first Meeting House (of which the small View at the head of this Preface is a representation) was built in the year 1689, the date of the passing of the Toleration Act. On July 16th, 1715, a mob, said to be inflamed by the eloquence of that zealous and fiery bigot, Dr. SACHEVERELL, attacked the Meeting House and destroyed nearly the whole of the interior by fire; as also the Meeting Houses at West Bromwich, Dudley, Oldbury, Cradley, and Bradley. In 1743, a portion of the congregation, adopting Calvinistic principles, separated from their fellow worshippers and built themselves a Meeting House in Carr’s Lane, a spot now rendered memorable by the 54 years’ pastorate of the Rev. J. A. JAMES. The Old Meeting congregation remained undisturbed till the Riots of 1791; their quaint and humble place of worship having lasted more than 100 years. The present Building was commenced 1792 and completed 1796.

Ministers of the Old Meeting House: - W. Turton, 1686 to 1716; D. Greenwood, 1700 to 1730; E. Broadhurst, 1714 to 1730; D. Mattock, 1732 to 1746; J. Wilkinson, 1739 to 1756; W. Howell, 1746 to 1770; S. Clark, 1756 to 1769; R. Scholefield, 1772 to 1799; N. Nichols, 1779 to 1784; J. Coutes, 1785 to 1801; R. Kell, 1801 to 1821; J. Corrie, 1817 to 1819; S. W. Browne, 1819 to 1821; H. Hutton, 1822 to 1850; C. Clarke, 1850 present Minister.

NEW MEETING HOUSE – In 1692 the second Presbyterian Meeting House was opened, under the name of the Lower Meeting House, by some of the Members of the Old Meeting Congregation, who separated in consequence of doctrinal differences, in a spot still bearing the name of the Meeting House Yard. Like the other it was attacked in 1715; the mob, however, sparing the walls, on a promised being made by the landlord (it was not the property of the congregation) that it should be put to other uses. The building, of which a portion yet remains, has since been used as a workshop. The congregation, thus compelled to removed, purchased in 1727 for £40 a piece of land about 32 yards by 20, situated on the northern side of a narrow lane now called New Meeting Street; here by erected the New Meeting House, which was opened April 1732. In 1764 the Trustees purchased, for £225, the three houses and land which were between the building and Moor Street; the houses were removed, and an open space obtained in front of the Meeting House. The celebrated Dr. JOSEPH PRIESTLEY was appointed a pastor of the place in 1780, and remained so till 1791, when he was driven away by the disgraceful proceedings of that year. During the re-building of the Old and New Meeting Houses both congregation worshipped together in a Chapel in Livery Street, (on part of the site now occupied by Billing’s Printing Office,) which they designated the Union Meeting House. The register of the New Meeting House having been lost, the Society could not recover damages from the Hundred; but, after much delay, obtained £2,000 from the Government towards the erection of the new building, which was opened July 22nd, 1802, to accommodate 1,200 persons. The strip of land in New Meeting Street adjoining the Meeting House was purchased in 1808, for a term of 500 years, for £400; here the school buildings were subsequently erected. Some of the members of the congregation desiring the place of worship and the schools to be removed nearer Edgbaston, several meetings were held in 1857 and 1858 to decide upon the subject; and in this latter year, on October 12th, at a meeting of the seat-renting members, held at Twelve o’clock at noon, it was determined that the “chapel and schools” should be “removed” to Broad Street. By a very small majority the resolution was carried – “That the Trustees be requested to take such measures for disposing of the present chapel, schools, and property in New Meeting Street as may appear to them expedient; and that the Committee now appointed be authorized to give such consent, on the part of the Congregation, to all legal measures for effecting such sale, or for appropriating the purchase monies to accrue therefrom, towards the new chapel and schools, as may be deemed necessary by the Trustees, or by the Court of Chancery, if it shall be found expedient to apply to that Court.”

The New Meeting House was privately sold to a Roman Catholic congregation in or about August, 1861, for £3,500; and the last Unitarian Service was conducted there on Sunday, December 29th, 1861. The site in Broad Street, previously referred to, consists in the right of building over the canal at the corner of St. Peter’s Place; and there an elegant Gothic church and school rooms have been built, which were duly opened on New Year’s Day, 1862, under the name – “Church of the Messiah.” To this building the memorial tablets of Priestley and others have been removed. The closing and sale of the New Meeting House caused much regret to many members of the congregation. Its central situation, large size, and the populous neighbourhood in which it situated, combined to make it a most desirable place for a mission chapel and schools; while is associations with Priestley rendered the area in front of it the most fitting site for a statue of that noble man, - noble alike for his learning, his religion, and his moral virtues, - of whose unflinching devotion to what he believed to be the truth of God, we feel assured, Birmingham will yet make a public recognition.

Ministers of the New Meeting House: - Sillitoe, 1692 to 1794; Thomas Pickard, 1705 to 1747; Samuel Bourn, 1732 to 1754; Samuel Blyth, 1747 to 1791; William Hawkins, 1754 to 1780; Joseph Priestley, LL.D., 1780 to 1791; John Edwards, 1791 to 1802; David Jones, 1792 to 1795; John Kentish, 1803 to 1853; Joshua Toulmin, D.D., 1804 to 1815; James Yates, M.A., 1817 to 1825; John Reynall Wreford, 1826 to 1831; Samuel Bache, 1832, present Minister of the Church of the Messiah.

Every obstacle was place in the way of the sufferers from the Riots claiming redress. The loss of some persons was much greater that their claim, and, to add to the injustice of the case, two years were suffered to elapse before the sums awarded were paid over. The following are the amounts claimed by and allowed by each: -

John Taylor, Esq. – Claim, £12,670 9s. 2d.; allowed, £9,902 2s. Thomas Russell, Esq. – Claim, £285 11s. 7d.; allowed, £100. William Piddock – Claim, £556 15s. 7d.; allowed, £300. John Harwood – Claim, £143 12s. 6d.; allowed, £60. Thomas Hawkes – Claim, £304 3s. 8d.; allowed, £99 15s. 8d. – Cox – Claim, £336 13s. 7d.; allowed £254. Parsonage House – Claim, £267 14s. 11d., allowed, £200. St. Dallax – Claim, £198 8s. 9d.; allowed, £139 17s. 6d. William Russell, Esq. – Claim, £1,971 8s. 6d.; allowed, £1,600. John Ryland, Esq. – Claim, £3,240 8s. 4d.; allowed, £2,495 11s. 6d. Old Meeting – Claim, £1,983 19s. 3d.; allowed, £1,390 7s 5d. George Humphreys, Esq. – Claim, £2,152 13s. 1d.; allowed, £1,855 11s. Dr. Priestley – Claim, £3,628 8s. 9d.; allowed, £2,502 18s. Thomas Hutton – Claim, £619 2s. 2d.; allowed, £619 2s. 2d. William Hutton – Claim, £6,736 3s. 8d.; allowed, £5,390 17s. Total Claims, £35,095 13s. 6d. Total allowed, £26,961 2s. 3d.

The altered condition of the buildings and the changes in the names of places render it difficult for those not well acquainted with the localities to discover the sites of the houses wholly or partially destroyed at the Riots. The following particulars will perhaps help the curious in this matter: -

Old Meeting House, Old Meeting Street, rebuilt. New Meeting House, now called St. Michael’s Roman Catholic Church, corner of Moor Street and New Meeting Street, rebuilt. Dr Priestley’s House, Sparkbrook, very little altered. Moseley Hall, much altered. Mr Humphrey’s, Sparkbrook, very little altered. Mr Hutton’s Town House, Hutton Place, 25, High Street, much altered. Mr Hutton’s Country House, Saltley, little altered. Bordesley Hall, (John Taylor, Esq.) Regent’s Park, Bordesley, pulled down, no remains. Baskerville House, (John Ryland, Esq.) Attwood’s Passage, Easy Row, top of Great Charles Street, the house itself little altered externally, but the surroundings very much so. Mr Russell’s, Showell Green, no remains. Edgbaston Hall, rebuilt, much altered. The Rev. Mr. Hobson’s, at Balsall Heath, internally destroyed, but restored. Mr Harwood’s (the property of Mr Piddock,) in the lane leading from the road between Moseley and Moseley Wake Green to King’s Heath, totally destroyed, but rebuilt. Dollax Chapel (now called Kingswood Chapel) and Parsonage, Kingswood Green, Hollywood, Alcester Road, rebuilt.

FREE CHRISTIAN SOCIETY – A large number of the Teachers of the late New Meeting Boy’s Sunday School, impressed with the importance of continuing their work in the populous and ignorant neighbourhood, where for upwards of 70 years they and their predecessors had done a large amount of good, determined, on the announcement of the removal, to remain working in that locality; more especially as the school buildings in St. Peter’s Place would not accommodate many more than two-thirds of the number of pupils then attending the New Meeting Schools. An effort to retain the old building proved unsuccessful. The Teachers then formed themselves into a body, called for the sake of distinction, “The Free Christian Society” and on September 7th, 1861, after a liberal Subscription among themselves, they issued a public appeal for aid to enable them to establish a Sunday School, as near as possible to the old place. Their appeal has been so far responded to, as to justify them in renting a convenient house at 117, New Canal Street, which was opened on January 5th, 1862, for the purposes of a Sunday School, (now attended by upwards of 150 pupils,) public religious worship, lectures, tract distribution, &c., &c., in all of which God has given them abundant success. Further help is yet needed, especially to provide a larger room for the services, lectures, &c., and for a girls’ school. Any profits arising from the sale of the present publication will be devoted to this object.

November 1862

AN AUTHENTIC ACCOUNT OF THE DREADFUL RIOTS IN BIRMINGHAM, OCCASIONED BY THE CELEBRATION OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION,

On the 14th July, 1791, WHEN THE PROPERTY OF THE INHABITANTS WAS DESTROYED TO THE AMOUNT OF Four Hundred Thousand Pounds.

CONTAINING

Extracts from a Number of Private as well as Public Letters. A faithful Copy of Dr. PRIESTLEY’S Letter to the Inhabitants of Birmingham; also of the Hand Bill signed and distributed under the Direction of LORD AYLESFORD and several of the Inhabitants; of the Inflammatory Hand Bill distributed previous to the Revolution Dinner; and a Letter from W. RUSSELL, Esq. wherein is a more accurate Relation of the Proceedings at the Hotel, than is given in any other Account whatever.

London: Published by H. D. SYMONDS, No. 20, PATER-NOSTER-ROW. 1791. [Price One Shilling]

THE EDITOR’S ADDRESS TO THE PUBLIC.

IN whatever Light the late Proceedings in Birmingham may be viewed, whether as a Struggle to preserve from Danger the Privileges of the Church, or as an envenomed Mob, enraged by the party Spirit of the Times, it is of the most serious and alarming Consequence to the Inhabitants of this Country. If, in the first Instance, it be viewed as tending to preserve unmolested the Rights and Privileges of the Church, it must naturally strike every reasonable Mind, that the Proceedings of a Mob could not in any manner effect that Purpose; nor is it a rational Thought that a Religion so pure as that of the Church of England can admit of any Persecution: and if it be taken upon the latter Ground, every one must be convinced, that, had a more speedy Exertion been adopted, in procuring the Military, the Ravages committed would, in some Measure, have been prevented much earlier than they were by the Mode pursued.

The Editor, not bigotted to either Party, hopes the following Pages will meet with the Satisfaction of the Readers, as he has selected them with the utmost impartiality, and introduced those Accounts only which he conceives are of undeniable Authenticity. He has only to add, that he does not in any Manner wish to pass his Opinion upon Political Differences, but wishes every man to follow the Dictates of his own Conscience, and sincerely hopes that Birmingham may continue in that Peace and Tranquillity, Unity and Prosperity, for which it has been distinguished so considerable a Time. The Editor therefore humbly submits the following Pages to the perusal of a free People.

London, July 25, 1791.

AN AUTHENTIC ACCOUNT OF THE RIOTS AT BIRMINGHAM ON THE 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th of JULY, 1791.

ANNIVERSARY meetings, in commemoration of the French Revolution, have been declared to be highly dangerous to the peace of this country, the inhabitants of which differ, in point of constitutional ideas, as widely from the democrates of Paris, as it is possible for contrariety of opinion to separate into two distinct forms of Government.

Flushed with the spirit of republicanism, and the victory which democracy had gained over monarchy in France, the too warm friends of that Revolution, in this country, entertained an idea that there was a probability of setting the people of England against their Sovereign, and of overturning the Constitution of the Empire.

For this purpose the most inflammatory pamphlets and advertisements have been dispersed throughout every part of Great Britain, and agents employed to ripen the lower orders of the people into an open aversion to the present system of government; and, to crown the whole, it was determined to have public feasts on the 14th of July, 1791, in the metropolis, and in the most populous and flourishing towns of the kingdom, as marks of veneration for, and approbation of, the Revolution in France.

An act so prejudicial to the constitution, and so subversive of the happiness and welfare of the public, became the subject of general animadversion; and as the great body of the people loved their King, it was natural to suppose that some decisive indignation would manifest itself against such measures; and sorry are we to add that, by accounts from Birmingham, it appears, that the loyal spirit of the numerous inhabitants of that great manufacturing town broke forth with the greatest violence, and fell with uncommon fury on those who were celebrating the anniversary of the new Government in France.

A public meeting, it seems, had been announced to commemorate the 14th of July at the Hotel in Temple Row, Birmingham, to which a number of persons repaired.

The consequence of this was, that in the evening every window in the hotel was smashed to pieces, but not before the company, in defence of their lives, had withdrawn in the best manner they could. It was in vain that the magistrates and peace officers attempted to stop the fury of the public, such feeble resistance only served to add vigour to their conduct, and push them forward to greater vengeance. They proceeded from the Hotel to Dr. Priestley’s conventicle, in powerful force, and having first torn down the pulpit, they then gutted the building, and setting fire to its furniture, made a triumphant bonfire of the whole. Not content, however, with reducing the desks, seats, pews, & c. to ashes, they demolished the building, and left not a stone of it unturned.

Whilst this was going forward, a detachment proceeded to the Doctor’s dwelling house at Fair Hill, which they razed to the ground, burning all his philosophical apparatus, his library and furniture. Fortunately the Doctor had made his escape a few minutes before their arrival, which so incensed the people (who certainly meant to sacrifice him) that they had an effigy made as nearly to resemble his figure, as the time would permit, and after hanging it up in the most ignominious manner, it was burned to ashes, amidst the shouts and acclamations of near then thousand people.

The old Meeting House was also burned, and the walls fell in about eleven o’clock; and at that time the New Jerusalem Meeting House it was thought would share the same fate, as well as the private houses of several of the leading revolution dinner men.

One private house, belonging to Mr Ryland, who was at the dinner, was pulled down. It was the house formerly inhabited by Mr Baskerville.

During the whole of those transaction, the populace continually shouted, “God save the King.” – “Long live the King, and the Constitution in Church and State.” – “Down with all the abettors of French Rebellion – Church and King.” – “Down with the Rumps.” – “No Olivers.” – “No false Rights of Man.”

To endeavour to appease this tumult, Lord Aylesford, at the head of several hundred respectable persons, marched to Dr Priestley’s house, and prevailed upon the persons assembled there to disperse; and it was thought his Lordship, who is much respected, would be able to stop this universal destruction of the property, and perhaps the lives of those it belonged to. All was tumult; - all was apprehension. There was no knowing where the fury of an enraged multitude might stop.

Several inflammatory and treasonable hand bills, respecting the glory of the Revolution in France, were distributed on the morning of the 14th in every part of Birmingham. We have collected them for the perusal of our readers, and shall give them with the other occurrences. The following is a copy of the first and principal one that was distributed.

“My Countrymen,

The second year of Gallic liberty is nearly expired: at the commencement of the third, on the 14th of this month, it is devoutly to be wished that every enemy to civil and religious despotism, would give his sanction to the majestic common cause, by a public celebration of the Anniversary.

Remember that on the 14th of July, the Bastile, that high alter and castle of despotism, fell!

Remember the enthusiasm, peculiar to the cause of liberty, with which it was attacked!

Remember that generous humanity that thought the oppressed groaning under the weight of insulted rights, to save the lives of the oppressors!

Extinguish the mean prejudices of nations! And let your numbers be collected, and sent as a free-will offering to the National Assembly.

But, is it possible to forget that your Parliament is venal; your Minister hypocritical; your Clergy legal oppressors; the Reigning Family extravagant; the Crown of a Great Personage too weighty for the head that wears it; too weighty for the people who gave it; your taxes partial and oppressive; your representatives a venal junto upon the sacred rights of property, religion and freedom?

But, on the 14th of this month, prove to the sycophants of the day, that you reverence the olive branch; that you will sacrifice to public tranquillity till the majority shall exclaim – “The Peace of Slavery is worse that the War of Freedom! – Of that day let Tyrants beware!”

No man, of honest principles, can read this without shuddering at the dreadful scene it was meant to realize? Rebellion is featured on its countenance, and republicanism centred in its bosom. But we shall forbear to make any further comments on the unfortunate business at present, and endeavour to put the public in possession of every fact relative thereto, by giving the extracts of all the different public letter received from Birmingham, as well as the private ones communicated to the Editor, and shall commence with the following, which we conceive contains the fullest account, though not the earliest in point of date.

Extract of a Letter from Birmingham.

“Birmingham never experienced so much distress. The mob have been marking and pulling down houses the whole day, and the riot is greater than ever. Unless some soldiers arrive early to-morrow morning, we are in very great apprehension that every dissenter’s house in Birmingham will be destroyed, and with them, no doubt, many other houses which were never intended.

The following is a list of the principal houses only that have been set on fire and pulled down. This list does not include those of inferior note, which have been pillaged by the populace, the number of which amounts to near one hundred:

Old and New Meeting House.

Mr Hawkes’s, jun. Mosely.

Dr. Priestley’s, at Fair Hill.

Rev. Mr. Coutts’s, at the Five Ways.

Mosely Hall, a very magnificent building, just out of the Town, belonging to the Duchess of Cumberland.

Mr. Humphrey’s, at the Turnpike.

Mr Hutton’s Town and Country Houses.

The Town and Country Houses of –Taylor, Esq. one of the Partners of the Birmingham Bank.

Rev. Mr Hobson’s, Balfol Heath.

Mr Ryland’s, Five Ways.

Mr Russell’s, Shovel Green.

Mr Harwood’s, King’s Heath, and

Dr Withring’s.

Mr Ryland’s house, which has been burnt down, was set fire to on account of his son’s having assisted in the escape of Dr. Priestley, whom the mob have pursued in different directions. Should the Doctor not be able to elude their vigilance, it is much to be apprehended that they will murder him, as he is considered the mischievous author of all the treasonable hand bills that have been circulated about the town, and which first produced the riot.

The mob have carried on their designs with a degree of system which it is almost incredible to suppose. Had they even received regular orders for their conduct, they could not have been more systematic in their proceedings. Not a house but what belongs to a dissenter has been pulled down.

The methodists, and followers the late Countess of Huntingdon, have all been protected. In the beginning of the riots the mob went to some of their houses, and questioned them concerning the doctrines which they professed, and on their declaring for Church and King, they assured that they should remain unmolested. The church people walk about as usual, without the smallest apprehension of danger.

The hotel belonging to Dadley, where the Revolutionist dined, has been only damaged by the windows being broken, the mob refusing to pull it down, because he was a churchman.

Mr Humphreys, whose house at the turnpike was pulled down, offered the mob four thousand, and afterwards eight thousand, guineas, if they would desist; but they declared that money was not their object, and that they pulled down his house because they considered him as a principal person concerned in the inflammatory hand bills. He is a very principal merchant in the town, and a gentleman much esteemed in his private character.

The town was extremely quiet during church time on Sunday; but no sooner was the morning service over than the riots recommenced. About sixty more houses are marked down for destruction. Among these every meeting house in the town. Dr. Withring, a dissenter, and first physician in the town, has had his house pulled down. The mob amount to about ten thousand.

The manner in which the houses are attacked, is by first sending in boys to break open the doors, and the leader of the mob then follow. At nine o’clock it was computed that the damage already done amounted to two hundred and fifty thousand pounds. Those which we have mentioned belong only to the principle persons.

The colliers in the neighbourhood of Westerby, and other adjoining villages, joined the mob; but the latter did not seem willing to have their assistance, and drove them out of the town, giving as a reason, that theirs was a just cause, and that they would not join with any rabble whose object might only be plunder.

No business of any sort is transacted. About sixty of the mob have been killed, besides a number of people on both sides much wounded. The dissenters have all of them fled from the town in the utmost consternation.

Birmingham, Friday, July 15

Ten o’Clock in the Morning.

The meeting at the hotel yesterday, to celebrate the French Revolution, was not so numerously attended as the friends to it expected. Eighty gentlemen only dined at the hotel, all of whom departed soon after five o’clock. The mob, that had began to assemble before, now commenced hostilities, by breaking all the windows of the hotel; and from thence paraded to Dr. Priestley’s Meeting House, which they set fire to. Another party, at them same time, set fire to the Old Meeting House; and both these places were soon burnt to the ground. Some adjoining houses took fire by accident, and were also consumed.

The mob then went to Dr Priestley’s dwelling house, at Fair Hill, about a mile and a half on this side of Birmingham, which they completely gutted, burnt the inside, all his furniture, books, manuscripts, and philosophical apparatus, and drank out all his wines, & c. They are at this moment pulling the next house down.

The mob now get valiant, and swear that Priestley’s man here must come down. In short, the whole place is in the utmost confusion.

Three o’Clock in the Afternoon

Since my last, the following houses have been pulled down, and the furniture removed and burnt; viz Messrs. Ryland’s, (late Baskerville’s,) Humphreys’ and Taylor’s. All these gentlemen are dissenters, and men of great property.

The house of Mr. Humphreys, which is near Dr. Priestley’s, was admired as an elegant structure, but now is a heap of ruins.

Lord Aylesford come into town this morning, and harrangued the mob. What his Lordship said appeared at first to have a good effect, and they promised him and the magistrates that they would disperse peaceably. They did not, however, keep their words, but increased in numbers, and become more riotous. We dread the night as we have no military with us.

This instant a large party of gentlemen, on horseback, are going to endeavour to save Mr Ryland’s house, or his furniture; but it is now known they are too late.

Six o’Clock in the Evening.

The rioters being divided into parties, and mediating the destruction of several other houses, about three o’clock in the afternoon, consternation and alarm seemed to have superseded all other sensations in the minds of the inhabitants; business was given over, and the shops were all shut up. The inhabitants were traversing the street in crowds, not knowing what to do, and horror was visible in every countenance.

About half past three the inhabitants were summoned by the bell-man to assemble in the New Church Yard. Two magistrates attended in an adjacent room, and swore in several hundred constables, composed of every description of inhabitants, who marched away to disperse the rioters, who were beginning to attack the house of Mr. Hutton, paper merchant, in the High Street. This was easily effected, there being not more than half a dozen drunken wretches then assembled on the spot.

From thence they proceeded to disperse the grand body, who were employed in the destruction of Mr Ryland’s house. On entering the walls which surround the house, then all a blaze, a most dreadful conflict took place, in which it is impossible to ascertain the number of the wounded. The constables were attacked with such a shower of stones and brickbats as it was impossible to resist. The rioters then possessing themselves of bludgeons, the constable were entirely defeated, many of them being much wounded. One person was killed, but of which party it is not yet known.

Eleven o’Clock at Night.

The mob being now victorious, and heated with liquor, every thing was dreaded. Several attempts were yet made to amuse them, but in vain. They exacted money from the inhabitants; and at ten o’clock at night, they began and soon effected the destruction of Mr. Hutton’s house, in the High Street, plundering it of all its property.

From thence they proceeded to the seat of John Taylor, Esq. banker. There five hundred pounds were offered them to desist, but to no purpose, for the immediately set fire to that beautiful mansion, which, together with it superb furniture, stables, offices, green-house, hot-house, & c. are reduced to a heap of ruins.”

Birmingham, Saturday, July 16.

In the forenoon the following hand-bill was distributed:

Friends and Fellow Countrymen!

“It is earnestly requested, that every true friend to the Church of England, and to the laws of his country, will reflect how much a continuance of the present proceedings must injure that Church and that King they are intended to support; and how highly unlawful it is to destroy all the rights and properties of any of our neighbours. And all true friends to the town and trade of Birmingham in particular, are entreated to forbear immediately from all riotous and violent proceedings, dispersing and returning peaceably to their trades and callings, as the only way to do credit to themselves and their cause, and to promote the peace, happiness, and prosperity of this great and flourishing town.

God save the King!”

Aylesford,

E. Finch,

Robert Lawley,

Robert Lawley, jun,

R. Morland,

W. Digby,

Edward Carver,

John Brooke,

J. Charles,

R. Spencer,

Henry Greswold Lewis,

Charles Curtis,

Spencer Madan,

Edward Palmer,

W. Villiers.

Twelve o’Clock at Noon.

The hand-bill has not produced the salutary effects which were wished.

This moment Mr Hutton’s country house, about two miles from Birmingham, is on fire. Universal despondency has taken place. People of all professions are moving their goods, some to places of private security, others into the country. Plunder is now the motive of the rioters. No military force is nearer than Derby, and nothing but military force can now suppress them.

Eight o’Clock in the Evening.

The rioters are now demolishing the beautiful house of Mr. George Humphreys, and that of William Russell, Esq. a little further on in the Oxford road. The shops are still kept shut up, and not military are yet arrived. Dreadful depredations are expected in the course of this night! The remains of several poor wretches, who had got drunk, and were burnt to death in Mr. Ryland’s cellar, have been dug out; one so much burnt, that he was recognized only by the buckle in one of his shoes. What could be collected of his remains have been just taken away in a basket. Another has been brought from the ruins of Doctor Priestley’s house, who is supposed to have been killed by a fall of some of the buildings.