William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

A Brief History of Placenames

Angles and Saxons

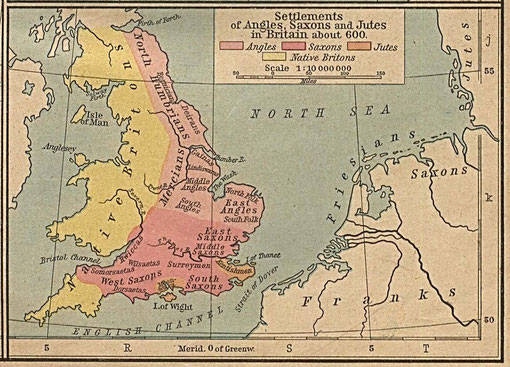

By far the greatest number of English placenames are of Anglo-Saxon origin, the oldest of which date from the 5th century. After the final departure of the Roman legions in 410 AD Germanic tribes came to England from an area centred on Frisia, a coastal region which stretched from the north-west Netherlands across north-western Germany and into south-west Denmark. Known to contemporaries as the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, they first attacked Britain for loot and pillage, but later came with the intention of and settlement. Some were already established here as mercenaries in the pay of local Romanised communities for protection against invaders from the sea.

The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had been established in the south-east by 450 AD. In most of England the Celtic language and culture seems to have been fairly rapidly replaced by that of the

Anglo-Saxons. The proportion of Celts to Anglo-Saxons has never satisfactorily been determined. It used to be thought that large numbers of Celts were driven out or chose to move west and north,

to Cornwall, Wales and the north-west of England. It is more likely that Celtic communities were taken over by Anglo-Saxon overlords, that there was considerable interbreeding and that it was the

Celtic language and culture that were lost, rather than the people.

Little archaeological evidence

Archaeology has yielded little evidence of Anglo-Saxon Birmingham. There are just two confirmed finds and a likely third. In 1877 a Victorian workman uncovered a rusty Anglo-Saxon spearhead while digging a new sewer in Harrisons Road, Edgbaston. This probably dates from the 10th century and can now be seen in the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. And at Longbridge near the Bristol Road South, was found a slender cone beaker made of glass. It is possibly of a type associated with a cemetery; however, no burial was found nearby. The Longbridge beaker is now in the British Museum, a remarkable survival of a glass object over thirteen centuries.

There is only one known site in Birmingham where archaeologists suspect surviving evidence of Anglo-Saxon occupation. Weoley Castle was occupied from Norman times as the manor house of

Northfield. By the 17th century the buildings were in ruins and the site is now maintained by Birmingham City Museums. On excavation archaeologists detected here an earth platform beneath the

12th-century building which they believed to be Anglo-Saxon. Deeper excavation is needed to confirm its age.

Intriguingly, the recent Bull Ring excavations found ample evidence of the Middle Ages, but no clues of Anglo-Saxons settlement. However, despite the dearth of archaeological evidence in

Birmingham we have a good idea of where most Anglo-Saxon settlements were and what they were called from documentary evidence. And the fact is, that most towns and villages in modern England

still bear a derivative of an Anglo-Saxon name.

Early documents

The first time that most of the Birmingham names (and indeed English ones) were written down was in 1086 when the officers of William the Conqueror recorded them in the Domesday Book. This is where the name of Birmingham itself is first to be found. Many villages had existed for 300 years previously, and further clues are to be found in Anglo-Saxon charters, the earliest of which, for Kings Norton, dates from the 7th century for our area. (Great) Barr is recorded in a charter of 957 AD as Bearre.

It is important to have on record early evidence of a placename in order to determine its original form. Many early documents have not survived and the first written records of some placenames do

not occur until the 17th century or later, by which time their original form may be unrecognisable.

Placenames: a complex study

The study of the history of placenames is complex. Names were given to settlements, to fields and to geographical features and were probably first devised locally for the practical purpose of distinguishing between the farm by the marsh, Marston, and the farm in a sheltered spot, Cofton; between the clearing in the birch wood, Bartley, and the clearing in the willow trees, Saltley; between the wood where pigs were pastured, Bearwood, and the burnt wood, Brandwood, and so on.

Placenames often showed who owned the land: Bordesley was Bord's clearing, Camp Hill was originally Kemp's Hill, and Druids Heath Drew's Heath. The use of a name such as Dud's farm might

vary depending on the circumstances: it could mean Dud's farmhouse, or the farmhouse and its nearby hamlet, or the farm and all its farmland. Subsequently, the name of an individual settlement

might be transferred to an area, to a manor or a parish. Dud's farm has come down to us as Duddeston. This mixed usage is still found in the present. A shopper going to the City Centre speaks of

going 'into Birmingham'; however, someone living on Castle Vale would equally say that they 'lived in Birmingham'; indeed people living beyond the city boundary, in Hollywood for example, might

also tell an outsider that they came from Birmingham.

Names may be transferred from local features to settlements. The name Balsall Heath was not originally a settlement name. It was the name of a geographical feature describing open scrubland

immediately around the Moseley Road north of Edgbaston Lane. However, from the end of the 18th century, as building development gathered pace, the name was gradually adopted for the whole

residential area between Ladypool Road and the River Rea.

Sometimes long-established placenames fall out of use. The sub-manor of Lindsworth is recorded as early as 705 and again in the Domesday Book; it survived into the 19th century as a farm name,

but is not used as a modern district name. Before 1800 Good Knaves End was a small settlement on Chad Hill around the junction of Westbourne Road and Harborne Road. The name is now unknown to

local residents. The placename, Tenchley predates that of Acocks Green by some 700 years but the name had fallen out of use by the end of the 18th century, to be replaced by that of Acocks Green,

named after a local family.

The locations to which placenames refer may change with time. From Anglo-Saxon times Stichford was a tiny settlement at the Cole river crossing, until the railway station opened in 1844. A

misspelling of the station name, Stechford was adopted and the focus of the locality moved to the station. As housing developed in the 19th century, Stechford 'village' moved to the top of Albert

Road. Stechford is also the name for a large district between Glebe Farm and Yardley whose focus is now along Station Road by the swimming baths.

Placenames: spoken not written

When most Anglo-Saxon settlements were named, the Old English language was not a written one. And as the language changed with time, the understanding of placename meanings also may have changed. Northfield derives from Anglo-Saxon nord feld. Feld did not originally mean a field in the modern sense, but open land as opposed to forest, possibly land already cleared when the Anglo-Saxon settlers arrived. The meaning changed during the Anglo-Saxon period to mean a large open field divided into strips worked by different individuals. From the Middle Ages as strips were consolidated and blocks of land were enclosed by individuals, the word began to take on its present meaning as a area of land demarcated by hedges or ditches and used as a single unit for animals or crops. In urban areas now the word is generally used to refer to grassland where sports are played. So the name of Northfield apparently makes sense to us now, but it is not the same sense that it made to people a thousand years ago.

Sometimes, names changed as the language changed and kept their original meaning. It is possible that Gravelly Hill had an Anglo-Saxon equivalent using the word greot which means gravel.

As the language changed so did the name, and its meaning today is still clear. However, the name of Greet, also derived from greot, can no longer be understood. Placenames may be altered to make

something meaningful out of a name whose meaning was lost, thus changing the original meaning. Hall Green was originally Hawe Green, named after common pasture near the medieval hall of the Hawe

family; it is easy to conjecture that after the Hawe family had gone, it made more sense to locals to name the green after the hall which still stood.

The earliest placenames

It may or may not now be possible to determine the original form of placenames. However, using a knowledge of the Anglo-Saxon language and of the way in which speech and spelling change over the years, by examining the earliest written examples of a placename, it is often possible to make an intelligent guess as to its original form and meaning.

The earliest names may have been topographical, names that described features of the local environment, such as 'red hill' or 'muddy stream'. Names with ing meaning 'the tribe of' and

ingaham, 'the home/ village of the tribe' may also be very old.

Much of the Birmingham area, especially to the east, was heavily forested in Anglo-Saxon times. Forests are not and never were made up of solid tree cover. There have always been natural

clearings caused by underlying soil conditions or fire or made by human hands. Field placenames signify 'open land' and may suggest land already cleared when the first settlers arrived.

Often trees had to be cleared to make way for agriculture, and names ending with ley, 'forest clearing' are common. Perhaps the term was used loosely to mean 'farmland in a forest area'.

Topographical names often related to features with economic significance. Woodland was an important resource and many names are found including the elements wudu or holt meaning

'wood', or hurst which means 'a wooded hill'. Holm or hole denoted 'flood meadows', and more or moor was boggy land along a stream both of which were used as

rich summer pasture.

Green is a common name. It usually indicated unenclosed rough grazing where local people had rights of pasture; squatters would often settle around the edges of the green and a

settlement would become established. Wicks, 'dairy farms' were pastures for cattle near rivers. They were set up to supply the main farm or village but eventually became villages in

their own right. Names with north, south, east or west were also villages to belonging to a main settlement some distance away. Aston seems to mean east farm, but it is uncertain which settlement

it was east of. Hays meaning 'enclosures' were farms with fields enclosed by fences or hedges, 'crofts' and are later Anglo-Saxon names.

The Anglo-Saxon period was a long one, over 600 years. Placenames may date from the earliest settlements in the 5th century or from after the Norman Conquest and well into the Middle Ages.

Celtic survivals

The majority of placenames in Birmingham are Anglo-Saxon, but a very small number of older Celtic names survive near Birmingham.

As the West Midlands seems to have been settled relatively late by the Anglo-Saxons, it is surprising how few Celtic names remain. Was it that the area was sparsely populated, or that many Celts

deserted the area as the new settlers advanced? It may be that the Anglo-Saxon occupation was late, but that when it came was very thorough.

Barr (as in Great Barr and Perry Barr): This is an Ancient British Celtic word, barr which means 'hill top'. Barr Beacon is such a prominent geographical feature that it must have always been a landmark and was perhaps also a place of special significance in Celtic times and earlier. It is easy to imagine the first Anglo-Saxon settlers pointing up at Barr Beacon and asking the locals what it was called. In Celtic, they replied, 'Hill.'

Bredon Hill: This derives from Ancient British, bre meaning 'hill' plus Anglo-Saxon dun meaning 'hill' plus 'hill'.

Penn: Pen is Ancient British for 'hill'. It seems likely that these Anglo-Saxon placenames containing Celtic elements were given early in the Anglo-Saxon settlement of the area.

Walsall: This is an Anglo-Saxon placename which refers to the Celts. Walas is an Anglo-Saxon word which means Welshman ie. Celt; ho means 'ridge'. Walsall thus means 'Welshman's

ridge.' This one reference to a single Celt suggests that this is likely to be a later name; but it nonetheless seems to point to the fact that at least one of the Ancient British had survived

and was in possession of land here.

There are two doubtful examples:

Deritend This may derive from Celtic dwr meaning 'water' + Anglo-Saxon geat meaning 'gate'. However, the name may derive from Anglo-Saxon deor geat meaning 'deer/ wild animals

gate'.

Monyhull Another possible Celtic survival from monadha meaning 'hill' + Anglo-Saxon hyll meaning 'hill'; or it could derive Anglo-Saxon Manna's (or Munda's) hyll meaning 'Manna's Hill'.

Two of Birmingham's rivers have Celtic names:

Cole: The Celtic name of this river means 'hazel trees'.

Tame This name too seems to be Celtic, but its meaning is uncertain: possibly 'dark' (river) or simply 'river'. The name derives from the same word as Thames and may pre-date the Celts.

(Rea derives from Anglo-Saxon aet thaere ea meaning simply 'at the water.')

The River Arrow near Lickey is a very unusual survival and appears to predate even the Celts. Its meaning is unknown. Nearby Tardebigge is similarly inexplicable.

Arden: The Forest of Arden which covered much of Warwickshire until the Middle Ages may have meant in Celtic 'high ground'. It may derive from the same word as the Franco-Belgian Ardennes.

The significance of these surviving Celtic names lies in the fact that they clearly show contact between post-Roman Celtic Britons and the incoming Anglo-Saxons. It has long been popularly believed that the invading Anglo-Saxons drove the Celts into hilly areas such as Wales and Cornwall. The perpetuation of these names under Saxon rule suggests a surviving Celtic presence.

The Vikings

From the 790s AD small Viking armies began to make annual raids on Britain. After 870 the Viking Great Army was resident in England and during the summer months moved around the country at will. By the 870s England was divided roughly along Watling Street, north and east of which was the Danelaw, south and west of which was English Mercia and Wessex.

There is no known evidence of Vikings in Birmingham. On two occasions the Great Army of the Vikings passed nearby, travelling from Shoeburyness in Essex to Buttington, Shropshire near Welshpool

in 893; and from the River Lea north of London to Bridgnorth, Shropshire in 895. Their route may well have taken them along Watling Street, the modern A5 which passes near Tamworth, through

Fazeley and close to Lichfield.

Typical Viking placename elements are:

by, village

thorpe, farm

thwaite, clearing

garth, enclosed land.

There are no Viking placenames close to Birmingham. The nearest are situated to the north and north-east of Tamworth eg. Thorpe Constantine, Appleby Magna, Appleby Parva; east of Coventry eg.

Copston, Griff, Monks Kirkby, Thurlaston, Wibtoft; and Wawen in Wootton Wawen on the A34 to Stratford is derived from Vagn, a Viking personal name. However, travel north and east of the A5

Watling Street into the Danelaw and here Viking placenames abound.

New developments

Until modern times it is probably true to say that placenames generally evolved by popular usage. However, in the 18th century deliberately planned housing developments began and names were coined for them. They were created to convey a particular impression of an estate, a practice that still happens to this day.

Ashted was an 18th-century development named after Dr John Ash, famous as the founder of the General Hospital whose estate this had been. The name of Bloomsbury was borrowed from London to add a

sophisticated urban gloss and give prestige to this 19th-century development, now Nechells Green, as was Islington to a high-class development near Five Ways.

Conversely the name of a rural feature was used for Europe's largest housing development when Chelmsley Wood was named in the 1960s. The Anglo-Saxon name of a wood that survives as a copse near

the present town centre was applied to a housing development for 80 000 people. And with post-industrial regeneration of the city at the end of the 20th century names such as Birmingham

International, Central Park, China Town and Eastside are designed to give a cosmopolitan feel to a city that derives a good deal of its income from national and international conferences and

exhibitions.

And finally,

How to Spell Birmingham

from William Hamper 1880 An Historical Curiosity: 141 Ways of Spelling Birmingham

The variety of spellings indicates that the pronunciation Brummagem had equal status with Birmingham until relatively modern times.

1086 Birmingeha;

1189 Brumingeham;

1200 Brimingham; 1214 Birminggeham; 1221 Burmingeham;

1227 Birmingham; 1227 Byrmyngham; 1235 Burmingham;

1245 Bermincham; 1247 Bermigham; 1248 Bermingham;

1256 Bremingeham; 1260 Burmincham; 1262 Burmigham;

1262 Burmungeham; 1285 Bernigeham; 1282 Byrmychiham;

1292 Birmyngham; 1292 Burmegham; 1297 Burmynchham;

1297 Bermygham;

1317 Burmicham; 1320 Birmyncham; 1320 Byrmincham;

1326 Bermyncham; 1330 Birmincham; 1332 Burmyncham;

1354 Burmincheham; 1337 Brimygham; 1377 Brymygham;

1387 Burmyngham; 1398 Bremyngeham;

1402 Brymecham; 1421 Birmyncham; 1421 Birmicham;

1424 Brymmyngham; 1438 Burmyngeham; 1440 Byrmyncham;

1457 Byrmycham; 1460 Brymygeham; 1469 Brymycham;

1476 Birmyngeham; 1486 Brimyncham; 1489 Birmycham;

1500 Brymyngham; 1504 Bromechham; 1506 Brymyscham;

1514 Brymingham; 1519 Brymmncham; 1520 Bormycham;

1520 Brymyngiam; 1522 Bremygiam; 1529 Bremycham;

1535 Bermegam; 1535 Brymmyngeham; 1537 Bremmycham;

1537 Brymedgham; 1538 Bromycheham; 1548 Bremyngham;

1549 Brymyncham; 1550 Burmycheham; 1553 Brimincham;

1573 Breemejam; 1576 Bromwicham; 1586 Bryngham;

1590 Brymicham; 1591 Bromecham; 1591 Brymigham;

1603 Bermicham; 1603 Bromicham; 1650 Bromegem;

1675 Bromwichham; 1679 Bromwicham; 1686 Brymmyngiam.

Take your pick!

William Dargue 08.04.09