William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

A Brief History of Birmingham

Georgian Birmingham

1714 - 1837

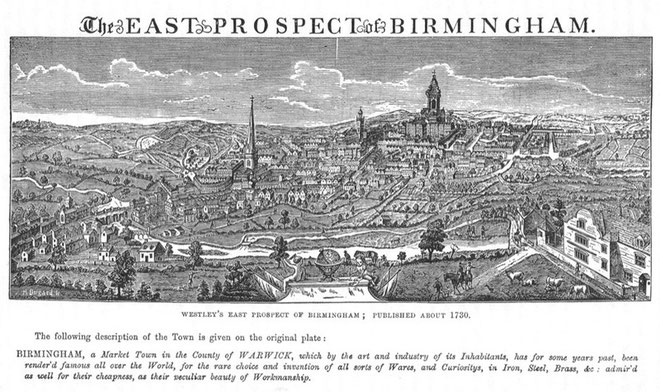

Image above: Westley's East Prospect of Birmingham c1730 reproduced in Dent 1880 'Old & New Birmingham' courtesy of Sally Lloyd on flickr. For a link to her Parishmouse website see Acknowledgements.

Georgian Birmingham saw a great expansion of industry in the town especially in the iron trades and in 'toy' making. Trade was encouraged by improvements in the national road network and by the building of canals; and the town grew rapidly. Thanks to the innovation and enterprise of industrialists and business people Birmingham became the first manufacturing city in the world. The effects were also felt in the rural hinterland where agriculture and industry became increasingly focussed on the densely populated town. Wealthy industrialists began to move out of the industrial centre to large houses in country estates in the surrounding area.

The 1660 population of 5 500 rose to over 23 000 by 1731 and to some 31 000 by 1770. During the 18th century Birmingham became the third most populous town in Britain after London and Bristol.

While the national population increased by 14%, the population of Birmingham increased by 900%. There was an enormous expansion of building within and at the edges of the town. Existing

timber-framed houses were given neo-classical facades or were demolished and rebuilt. In contrast to the old timber-framed buildings, the new houses were neo-classical in style and brick-built,

often with three storeys instead of two as previously. With few exceptions which include parts of the Jewellery Quarter and a handful of late-Georgian buildings, all of this development was

demolished during the 19th century. An important 18th-century survival, however, is the network of canals in the City Centre.

Up to c1700 most new building had been carried out between Edgbaston Street and New Street. After 1700, however, ambitious landowners began to lay out fashionable new estates on the fringes of

the built-up area. Building began on former Priory land around St Philips Church which was built from 1711; and the Pemberton estate was laid out during the first two decades of the century with

The Square, now Old Square, and surrounding streets consisting of high-quality Georgian houses for wealthy industrialists and gentlemen of independent means. In 1730 the Weaman estate was laid

out around Whittall Street. But the new residential developments which were aimed at the increasing middle class and artisan class, were not immune from the proximity of industry the profits of

which had caused them to spring into being in the first place: Kettle's Steel Houses had been built on the street named after them by 1731. Much of this district was soon to develop into the Gun

Quarter with other central districts becoming increasingly packed with dark dense courts.

The Jennens family were the first to realise the attraction of having a new church built at the centre of their estate. They paid for the construction of St Bartholomew's in 1749 at the junction

of Masshouse Lane and Bartholomew Street. Others followed their example: St Mary's in Whittall Street was built for the Weaman estate in 1774, St Paul's on the Colmore estate was built in 1779

and St James the Less was built in 1789 just outside the town on the Ashted estate.

The Colmore estate was laid out from Colmore Row around the family's New Hall between Summer Hill and Constitution Hill. Plots of various sizes on 120-year leases were aimed at small craftsmen,

especially manufacturers of jewellery and toys, who were required to build substantial houses here. (See The Jewellery Quarter.)

The Gooch estate, originally lands of the lord's demesne, around Sherlock Street was laid out from 1766. The Holte estate at Gosta Green was initially let to extract clay for brick-making in 1744; the extent of the quarry can still be seen east of Woodcock Street. It was not until the first quarter of the next century that streets were laid out here for housing. The Bradford estate around the street of the same name had been laid out by the end of the century (See Cheapside.).

Birmingham's first historian, William Hutton arrived in Birmingham at the age of 17. It is clear from his autobiography that his first impression of the town never left him.

Upon Handsworth heath, I had a view of Birmingham. St. Philip's Church appeared first, uncrowded with houses, untarnished with smoke, and illuminated with a Western sun. It appeared in all the pride of modern architecture. I was charmed with its beauty, and thought it then, as I do now, the credit of the place.

I had never seen more than five towns; Nottingham, Derby, Burton, Lichfield, and Walsal. The out-skirts of these were composed of wretched dwellings, visibly stamped with dirt and poverty. But

the buildings in the exterior of Birmingham rose in a style of elegance. Thatch, so plentiful in other places, was not to be met with in this.

I was surprized at the place, but more at the people. They possessed a vivacity I had never beheld. I had been among dreamers, but now I saw men awake. Their very step along the street shewed

alacrity. Every man seemed to know what he was about. The town was large, and full of inhabitants, and these inhabitants full of industry. The faces of other men seemed tinctured with an idle

gloom; but here with a pleasing alertness. Their appearance was strongly marked with the modes of civil life.

Edited

The 18th century saw a huge expansion in the range and size of Birmingham's industries. By the end of the century Birmingham was the world's major supplier of steam engines from Boulton & Watt; it was the first and retained its status as the foremost manufacturing city in the world throughout the following century.

The town continued to build on its success in small metal industries especially in cutting tools and blade-making after the Civil War. Birmingham is poorly situated for transport: the town is

built on a plateau, it is 20 miles from a navigable river, and has few natural resources. However, the development of turnpikes and canals greatly improved Birmingham's ability to import raw

materials and to export manufactured goods. By specialising in small products using a high degree of skill and by taking full advantage of water power from small rivers and streams, enterprising

manufacturers successfully branched out into gun-making, brassware and glass-making. Many watermills converted to metal working and windmills were built to grind the corn.

There is little surviving evidence of earlier gun-making, but in the wars against the French from the 1690s to 1713 the industry was able to supply 40 000 flintlocks to the government. By 1750

gunmakers Farmer & Galton were exporting 12 000 guns a year to Africa alone. During the Napoleonic wars 1803-1815 Birmingham gunmakers supplied two thirds of the guns used by the British army

as well as large numbers of swords and cutlasses for both the army and navy. Most gun-making was carried out in small workshops in the Gun Quarter on the Weaman estate around St Mary's Church

Whittall Street near the present St Chad's Cathedral. Sketchley's 1767 Directory of Birmingham lists some 62 workshops involved in gunmaking. (See The Gun

Quarter.)

Brass assumed increasingly greater importance for the town and was used especially for small fashionable items known then as 'toys', items such as buckles, buttons, door handles, snuff boxes

ornaments and jewellery. About 1680 Birmingham toys were referred to disparagingly as 'Brummagem ware' after counterfeit groats made here, but increasingly Birmingham products gained a name for

innovation and quality. Much of this reputation was directly attributable to Matthew Boulton. By the 18th century gold and silver and a variety of alloys were in use for toy-making and jewellery

was made on the Colmore's Newhall estate, now the Jewellery Quarter. By 1759 there were 20 000 people were employed in Birmingham toy-making whose products were traded widely in Britain, in

mainland Europe and in America.

However, iron was Birmingham's foremost industry. Returns for Birmingham's Warwickshire manors made in 1683 show that Birmingham had 202 smithies (about half of them in Digbeth and Deritend),

Bordesley had 20 (mainly in Deritend), Erdington 15, Castle Bromwich 13, and Little Bromwich, now Ward End had 6 smithies. An enormous variety of iron products was made and traded throughout the

British Isles and the world: tools, household fittings, kitchenware, door handles and hinges, knives and forks, etc. Much iron manufacture and trade was in the hands of the Jennens family who

worked both Aston Furnace and Bromford Forge, owned much woodland in Warwickshire to supply wood for charcoal and also had a trading base in London. In 1663 John Jennens owned a very large Queen

Anne style house on Birmingham High Street and paid tax on 25 hearths.

William Dargue 18.04.09