William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

Edgbaston

formerly in Warwickshire - one of the Domesday manors of Birmingham and an ancient parish

B15 - Grid reference SP057847

Celboldestone: first record in the Domesday Book 1086

Celboldestone is a Domesday Book spelling mistake, and probably not the only one caused by the incorrect copying of a Norman scribe. William the Conqueror's survey of his kingdom was carried out for tax assessment purposes and was compiled by teams of commissioners who travelled England in seven circuits. It is unlikely that commissioners visited every manor or village, but sat primarily at county courts and hundred courts (A hundred was an Anglo-Saxon subdivision of a county). Perhaps the main landowners or their stewards came individually to give details.

The speed with which the survey was completed, just over a year, strongly suggests that existing Anglo-Saxon manorial documents provided the bulk of the information. The truth of each entry had

to be sworn by the shire reeve (sheriff), by all the barons and their Frenchmen, by the priest and the reeve (the chief manorial official), and by a jury of six villagers. The reports, which were

written in abbreviated Latin, were then taken to Winchester where the King's chief steward had them copied in handwriting that is clear enough to easily be read to this day. However, the last

section of the Domesday Book, which includes the West Midlands, appears to have been more hastily written. There was plenty of room for error.

Egebaldestone is a more likely a name than Celboldestone. There was an Anglo-Saxon personal name Ecgbeald; ecg meant 'edge' ie. 'sword', bald meant 'bold'. So this placename was Ecgbeald's tun meaning 'Ecgbeald's farm'. The original site of Ecgbeald's farm is unknown but Edgbaston Hall is known from the Middle Ages as a moated manor house off Edgbaston Park Road and is a likely site. There seems not to have been a nuclear village of Edgbaston, rather a manor of scattered farmsteads.

Interestingly, Robert Morden's 1721 Map of Worcestershire records the name as Edgbarston, which may indicate the local pronunciation at the time. The 1841 Census records it as Edgebaston.

This first settlement of Edgbaston lay along the Birmingham sandstone ridge. This geological feature runs roughly north to south from Lichfield, through Birmingham City Centre and down to Bromsgrove. Sutton Coldfield, Pype Hayes, Witton, Erdington, Birmingham and Edgbaston were other early Anglian settlements on the sandstone ridge.

The Anglians had arrived here along the valleys of the Rivers Trent and Tame and the area became part of the Anglian kingdom of Mercia c585. An incentive to settle here was that soil overlying the sandstone here was easier to plough and, where the sandstone met the clay lands to the east, there were abundant natural springs.

Although Birmingham abounds with Anglo-Saxon placenames, archaeological evidence of the period is extremely scarce. However, in 1877 a rare Anglo-Saxon find was made during sewage work, when the Edgbaston spear was unearthed in Harrisons Road. This corroded and visually unimpressive object dates from the 10th or 11th century and can now be seen in the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery.

Well worth a visit - St Bartholomew's Church.

First mentioned in 1279, the foundation of this church is certainly earlier. Now the parish church of Edgbaston, this was formerly the chapel of Edgbaston Hall. The nave is 14th-century and

stands on the site of the first building here. The north aisle and arcade are late 15th-century and were paid for by lord of the manor Richard Middlemore, and the tower of c1500 paid for by his

wife Margerie. Their son, Humphrey, became a Carthusian monk and was martyred 1535 during the Henry VIII's persecution of Roman Catholics. Stained glass in the west window of the south arcade is

a modern depiction of this.

The church building was severely damaged during the Civil War 1658-1684 when it was occupied by Parliamentary troops. The roof lead was melted for bullets, while the roof timbers and stone were used to barricade Edgbaston Hall. Ten years after the Restoration of the Monarchy, local people began to rebuild the ruined church at their own expense but were unable to finish it. In 1683 they were granted King's Letters Patent to request charitable donations from church collections in Warwickshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Leicestershire and Shropshire. Donations must have been forthcoming because the restoration of the church was subsequently completed. This, however, was only one of a series of restorations, alterations and extensions over the years.

In 1725 a new owner of the hall and manor, Sir Richard Gough of Perry Hall had the church restored at his own expense. In 1810 the nave and north aisle were given a single low-pitched roof in a

major restoration when the interior was almost totally rebuilt. In 1845 the roof was raised by two metres to allow for galleries to accommodate more of the increasing population of Edgbaston.

Similarly in 1856 J A Chatwin built a south aisle, and in 1885 a chancel paid for by Middlemore descendants, brothers William, James and Richard Middlemore. The present chapels were built, the

nave widened, the clerestory raised and new more steeply pitched roofs were built. In 1889 a second south aisle was made as the wealthy population of the district continued to grow. Apart from

late-15th-century work in the north and west walls of the north aisle and nave and the early-16th-century lower part of the tower, the church now is practically all Chatwin's work. The church is

Grade II Listed.

There are monuments here in memory of the Gough-Calthorpes, the current manorial family, and a notable wall monument by William Hollins which depicts a snake twisted round a stick and foxglove.

This commemorates William Withering, the discoverer of digitalis. A bust also by Hollins of Jean Marie de Lys, is a memorial to the founder of the Deaf & Dumb Institute. In the churchyard is

a monument to the noted Birmingham architect, J A Chatwin 1830-1907 who carried out extensive work on the building. During term time Edgbaston's eight bells are rung for services by the

Birmingham University Society of Change Ringers.

Edgbaston Mill, later Avern's Mill, lay on the River Rea just below its confluence with Bourn Brook near Edgbaston Road. This was manorial corn mill of Edgbaston and is first

recorded in 1231. The Avern family owned the mill by 1788 and still held it in the early 19th century. By 1880 the mill was no longer in use and its buildings were let as a farmhouse not now

standing. Another watermill, Over Mill took its power from the damming of Chad Brook. Two pools were then formed, known as Edgbaston Upper and Lower Pools. The mill is known to have been in there

by 1557, when it was used by the King family as a fulling mill, but by 1624 it was being used for blade making, a function it performed until the mid-19th century. During the 1850s the mill was

used by the Spurrier family for rolling gold and silver. However, the business moved in 1875 to Bournbrook Mill. This mill was no longer used and the buildings fell into disrepair. There was

visible evidence of the millhouse until the 1960s. The Lower Pool, sometimes known as Spurriers Pool, is now overgrown.

The pool and surrounding land was classified in 1986 as a Site of Special Scientific Interest SSSI and is now managed by the Birmingham Natural History Society in conjunction with Edgbaston Park

Golf Club. Water-filled areas support a wide variety of pond and swamp plants. Much of the site has been colonized by trees that favour damp sites, such as varieties of willow and alder. The

drier ground has developed into woodland dominated by oak and birch among which have been planted beech and some exotic tree species. The nature reserve, which is accessible only to members, is

also known for its bird life which includes grebes, reed warblers and woodpeckers.

Descent of the manor

After the Norman Conquest William FitzAnsculf was the first recorded overlord of Edgaston among many other local manors, with a Norman, Drogo holding the manor from him. Two Anglo-Saxon tenants Aski & Alfwy held it in the time of King Edward. Subsequent lords took the name of the manor as their surname: Henry de Edgbaston is recorded in 1284. The descent passed down through his family to Isabel who married Thomas Middlemore sometime around 1393. His family held lands in Solihull and Studley but he himself is described as being a citizen of London. The manor then descended through the Middlemores for three hundred years. However, during the Civil War Richard Middlemore was not only a royalist but also a Roman Catholic. The manor was sequestered in 1644 and handed over for Parliament to the charge of Colonel Fox, the commander of the local parliamentary garrison.

When Richard died in 1647 his son Robert petitioned for the manor. In 1651 his son Richard aged three was placed as the ward of Sir Edward Nichols of Faxton, Northamptonshire to be brought up as

a protestant. Robert was dealing with the manor in the 1670s. His daughter Mary married Sir John Gage and on her death in 1686 the manor passed to her two daughters. In 1717 they sold their

Edgbaston estates with the manorial title to Sir Richard Gough, the younger brother of Henry Gough of Perry Hall. The manor was then inherited by his son, Sir Henry, who was created a baronet in

1728. His son, also Henry, inherited and he was created Baron Calthorpe in 1796. The manor then descended with the title until the death of Augustus, the 6th Lord Calthorpe in 1910. Edgbaston

then passed to Augustus's eldest daughter Rachel who married Fitzroy Hamilton Lloyd-Anstruther, who changed his name by royal licence to Fitzroy Hamilton Anstruther-Gough-Calthorpe, 1st Baronet

Anstruther-Gough-Calthorpe of Elvetham Hall, Hampshire. The present lord of the manor is Rachel's grandson, Sir Euan, 3rd baronet.

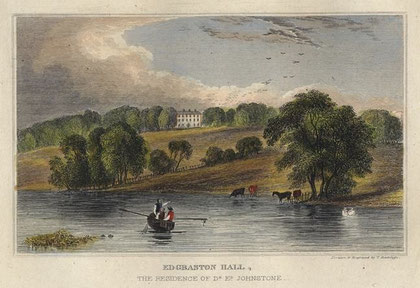

Edgbaston Hall was the medieval manor house which was built within a moat of which no trace now survives. In the 15th century the Middlemores, lords of the manor from the 1400s to the 1700s built a new timber-framed hall to replace it just south of the original site. During the Civil War in 1644, as Roman Catholics and royalists, they had their home seized in a raid by Colonel 'Tinker' Fox with sixteen parliamentary troops who were reinforced by two hundred Birmingham metal-workers. The roof timbers of neighbouring Edgbaston church were used to barricade the hall, the roof lead was used for making bullets and the bell metal sold. Both church and hall were held until the end of the war as a fortified base for raids on royalist north Worcestershire.

Tinker Fox disappeared without trace after November 1646; local legend had it that he was the masked executioner of King Charles I, although there is no evidence to support this.

The hall was burned in the anti-papist riots of 1688 on the accession of William & Mary. After the Middlemores sold the estate, the hall was completely rebuilt in neo-classical style in 1718

for Sir Richard Gough to its present appearance. The park was landscaped by Lancelot Capability Brown for Sir Henry Gough c1776. After the removal of the Gough-Calthorpes to the south of England,

the hall was let to various wealthy Birmingham people: William Withering, the discoverer of digitalis lived here 1786-1791, and its last occupant in 1896 was the City's first Lord Mayor, Sir

James Smith.

Following King James II's Declaration of Indulgence which allowed Roman Catholics freedom of worship, the church of Ste Marie Magdelene was erected in 1688 in Masshouse Lane in the town. It was

the first Roman Catholic church to be built in England after the Reformation. But only two months later it was destroyed by an anti-papist mob, and Roman Catholics came to worship at Masshouse

Farm in Pritchatts Road, Edgbaston. The register here of Roman Catholic baptisms, marriages and deaths is the oldest surviving post-reformation register in England, and is now housed in the

Oscott College Museum. Services continued here until 1786 when St Peter's opened in Broad Street on the site where the International Convention Centre now stands. The present Masshouse is a

17th-century timber-framed building originally built as a farm house.

Take a look at the Edgbaston Guinea Gardens which are occasionally open to the public. Situated off Westbourne Road these are the last example of 18th-century working-class allotments which were to be found all around the outskirts of the town. The annual rent was traditionally one guinea ie. £1. 1 shilling. By 1878 most of these gardens had disappeared underneath the expanding town.

This site, a little further away from the centre than most of the others, survived, although it was previously much bigger. Land was lost to the railway in 1840, to houses in Westbourne Road 1860-1880, to Edgbaston Lawn Tennis Club 1918-1939, and to Edgbaston High School in the 1950s. Some of the original lay-out was also destroyed by the BBC who used part of it to create the world's first television garden with Percy Thrower. In the 1970s the City Council demolished the original summer houses and sheds.

The Guinea Gardens, which are Grade II Listed on the English Heritage Register of Historic Parks and Gardens, lie within the Edgbaston Conservation Area and are a unique survival in Birmingham vigorously defended by a tenants' committee.

Take a look. Opened in 1815, the Worcester & Birmingham Canal cuts directly though the Gough-Calthorpe's Edgbaston estate. The Calthorpes had protested vigorously at this intrusion on their land, canals then being viewed much as motorways are now.

Eventually the canal was permitted to cross the Calthorpe Estate in a cutting with no access points, wharves or commercial buildings. Although the family could have profited from such development, they may have taken a longer-term view that more money could be made from high-class residential development.

The canal cut through Edgbaston has long been known to boatmen as 'the Garden Reach'. The Edgbaston Tunnel runs for 95 metres beneath Church Road. Twenty-three years in the building, the canal leaves Gas Street Basin for Worcester and giving Birmingham access to the River Severn and the Bristol Channel.

Coal and industrial products were sent south, and grain, farm produce and building materials were brought north to Birmingham. An important cargo from the 1830s on this line was salt from Droitwich and Stoke Prior, and from the 1880s Cadbury's brought their raw ingredients to the wharf at Bournville.

Well worth a visit - the Botanical Gardens.

The influence of the Calthorpe family is everywhere in Edgbaston. Birmingham Botanical Gardens in Westbourne Road, laid out on the site of Holly Farm in 1832, were supported with financial help from the Calthorpes. The gardens cover more than 7 hectares and were designed by the famous landscape gardener, John Loudon, most of whose initial lay-out remains.

Original buildings include the entrance hall, the tropical house and the palm house all of which are Grade II Listed buildings. Many trees planted in 1840 still thrive as well as older field trees from the hedgerows of Holly Farm. The gardens are listed in the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.

Urbanisation

An impression of Edgbaston is given by the Birmingham Daily Mail journalist Eliezer Edwards, who came here from Kent in 1837. He wrote of his initial forays around the town and its suburbs:

Beyond Five Ways there were no street lamps. The Hagley Road had a few houses dotted here and there, and had, at no distant time, been altered in direction, the line of the road from near the present Francis Road to the Highfield Road having at one time curved very considerably to the left, as anyone may see by noticing the position of the frontage of the old houses on that side.

All along the straightened part there was on the left a wide open ditch, filled, generally, with dirty water, across which brick arches carried roads to the private dwellings. 'The Plough and Harrow' was an old-fashioned roadside public house. Chad House, the present residence, I believe, of Mr. Hawkins, had been a public house too, and a portion of the original building was preserved and incorporated with the new portion when the present house was built.

Beyond this spot, with the exception of Hazelwood House, where the father of Rowland Hill, the postal reformer, kept his school, and some half-dozen red brick houses on the right, all was open country. Calthorpe Street was pretty well filled with buildings. St. George's Church was about half built. Frederick Street and George Street, for they were not 'Roads' then, were being gradually filled up. There were some houses in the Church Road and at Wheeleys Hill, but the greater portion of Edgbaston was agricultural land.

Sir Richard Gough had bought the Edgbaston estate and manor from the Middlemore family in 1717. For nearly one hundred years the estate passed down the generations and was run as a traditional

estate of the landed gentry. There was no nucleated village in the manor other than a small concentration of cottages by the Chad Brook ford on Harborne Road at Good Knaves End.

During the 18th century the family, who lived at Edgbaston Hall, was elevated to the peerage and through marriage took the name Calthorpe. Their first foray into leasing land for building was for

a small number of plots at Five Ways between the Hagley Road and Harborne Road. But it was to be George, 3rd Lord Calthorpe in the late-18th century who began to develop the estate into the

spacious tree-lined quality district that it still is. The first of the family not to live at Edgbaston Hall, he worked closely with his land agent, John Harris.

Calthorpe saw that there were a large number of wealthy entrepreneurs in Birmingham who would welcome the chance to buy a house of quality in semi-rural surroundings amongst people of their own

class. Development started nearest the town at Five Ways and worked outwards. The quality of the estate was maintained by selling not freehold plots but leaseholds on large sites with strict

conditions as to the style of housing to be built. There would be no industry, nor even any shops.

Edgbaston's population grew from about a thousand residents in 1801 to almost 4000 in 1831. Building continued along the Hagley Road and Harborne Road to reach Portland Road by 1863. In the years

to the end of the century the rest of Edgbaston was gradually developed but always with the same principles regarding the spaciousness of the plots and the quality of the housing permitted to be

erected on them. Edgbaston quickly became the home of Birmingham's rich and famous: R L Chance, R W Dale, George Dawson, Joseph Gillott, and members of the Avery, Barrow, Cadbury, Chamberlain,

Kenrick, Martineau, Pemberton, Ryland and Sturge families lived here.

There is such a variety of so many houses of good quality in Edgbaston that it is possible here to highlight only a few examples. On the Bristol Road a large number of houses are Grade II Listed

which lie within Edgbaston Conservation Area; some are very substantial and have service wings and coach houses dating from the 1830s' early development of the Calthorpe Estate: No.249 Park Grove

House and stable block is an early Calthorpe house of 1814 set at the end of a long carriage drive. It was gothicised c1840, c1850 and c1880 with iron pointed windows and internal oak panelling

and extended c1870 to the rear by the service wing. There was formerly a chapel on the ground floor. The stable block was added c1850. The house now forms part of the Priory Hospital.

Lee Crescent consists of terraces of more modest middle-class houses in Regency style which date from the 1830s: Nos.30-58 consecutively are Grade II Listed buildings and form the Lee Crescent Conservation Area.

In Ampton Road Nos.1 & 2 are early stuccoed houses in italianate style with coach houses which also date from c1830 and lie within the Edgbaston Conservation Area. No 8 has a Birmingham Civic Society blue plaque commemorating the birth of the modern game of lawn tennis by solicitor and sportsman Major T H Gem.

In Arthur Road No.1 Aston House is a 2-storey Grecian-style stuccoed villa of c1840. The imposing central entrance is decorated with a scrolled acanthus design and has a large

pediment above; it boasts a 2-storey coach house.

Wellington Road has a large number of Grade II Listed houses dating from the 1840s: Spring Cottage has crenellated Folly Tower and was probably a reconstruction of an existing 18th-century cottage or farmhouse. No.12 Ampton Road is a significant Grade II* Listed. building. Built by Birmingham architect John Henry Chamberlain in 1855 as his own house; it is a large fine building in Victorian gothic; his monogram, JHC may be seen on the front of the house.

No.16, the Calthorpe Estate Office in Norfolk Road was built c1860 in the Edgbaston neo-classical style. It has a coach house and stables and additions of c1870. The interiors date from the time

of the 1870 extensions include dark woodwork, Jacobean-style mahogany staircase, carved fireplaces and panelled doors. It is a Grade II Listed building. J H Chamberlain built No.24 Priory Road in

1893 for the editor of the Birmingham Post, the well-known as a Birmingham historian, John Thackeray Bunce. This red-brick gothic house with stone dressings and a prominent chimney stack is now

part of Priory Hospital. W H Bidlake's The Garth on Edgbaston Park Road of c1900 is designed in a Tudor-cum-Jacobean style and is a good example of this architect's domestic design. Bidlake

designed the house for Ralph Heaton of the Birmingham Mint; it belongs now to Birmingham University.

The only Grade I Listed domestic building in Birmingham is in Yateley Road. No.21 was designed by the influential Arts & Crafts architect, Herbert Tudor Buckland as his own house. Buckland

1869-1951 was born in Wales but educated at King Edward VI School, Birmingham and at the Birmingham School of Art. He trained under the Castle Bromwich architect, C E Bateman, and set up in

independent practice in 1897. He followed William Martin as architect to the Birmingham School Board in 1901 and was responsible for designing the Elan Valley model village. Yateley Road boasts a

number of Buckland's Arts & Crafts houses, of which his own, No.21 home in 1899 is the best. It retains its original interior and has a Gertrude Jekyll garden.

Although some large houses were replaced by small developments in the second half of the 20th-century, Edgbaston remains a high-class Victorian suburb with a great number of Listed buildings and

includes the conservation areas of Edgbaston and St Augustine's.

See also Rotton Park.

Click to enlarge the images in the Gallery of Edgbaston domestic architecture below.

Well worth a visit - the Oratory.

On the Hagley Road stands the Oratory, from 1852 the headquarters of the English Congregation of the Oratory of St Philip Neri founded by John Henry Newman at Maryvale in 1848.

The first church building was rebuilt in 1903 as a memorial to Cardinal Newman who had died in 1890. It was consecrated as the Church of the Immaculate Conception in 1920.

Standing back from the Hagley Road and hidden behind St Philip's Grammar School, the church is accessed via a vaulted passage beneath part of the school building which opens onto to a cloistered

courtyard.

The church was designed by E Doran Webb in a Renaissance style and has a distinctive copper-clad a dome on a drum with large rectangular windows which stands above the crossing. Inside the nave is tunnel-vaulted Corinthian colonnades separating the narrow side aisles with their side chapels in shallow bays. There are shallow north and south transepts and a short apsidal chancel.

In contrast to the rather plain exterior of limestone ashlar, the interior of the church is very ornate and decorated with coloured marbles and mosaic. The high altar is based on that at the

Certosa di Pavia in Italy; and the tabernacle is based on that in St Peter's in Rome. The altar of the Lady Chapel in the north transept is from the church of Sant Andrea della Valle in Rome.

Altars beneath the choir gallery and in the chapel of St Charles Borromeo are from the old church. Cardinal Newman's remains were transferred from the cemetery of the Oratory's Rednal Retreat to

this latter chapel in 2008. St Phillip's chapel on the south side dates from additions made to the old church by John Hungerford Pollen in 1858. The shrine of St Philip Neri in the north-east

chapel, by G B Cox, is based on that in the Chiesa Nuova in Rome and was added c1930.

Facing the Hagley Road is the Oratory Priests' House. This 3-storey 5-bay building in red brick in an Italian Renaissance style was home Cardinal Newman's home from 1852 to 1890 and his rooms

have been preserved in their original condition. Alongside is the original building of St Philip's Grammar School, now St Philip's Sixth Form college, which was built in 1859 by Henry

Clutton.

As Edgbaston was urbanised during the 19th century three new churches were built. St George's church at the junction of Westbourne Road and Calthorpe Road was originally a small church with a nave and aisles in 1838 and paid for by Lord Calthorpe. Built in stone, it was designed in an early English gothic style by J J Scoles. A chancel was added in 1856 by C Edge. The church was much enlarged in 1885 with a new nave and chancel with elaborate details by Birmingham architect J A Chatwin, the new part completely dominating the original. This Grade II Listed church has a single chiming bell.

At the corner of Elvetham Road and St James Road St James' Church was built in 1852, with all building costs being met by Lord Calthorpe. Designed by S S Teulon in a French

gothic style, this stone-faced church was built to house a large congregation. There broad aisleless nave with the transepts make a wide centralised preaching space much in the Georgian manner.

There are rose windows in the transepts and a south-east tower with an internal buttress typical of Teulon and a low spire. There was a single tolling bell. This Grade II Listed church is now

closed and converted into dwellings.

St Mary & St Ambrose at Raglan Rd on the Pershore Rd was originally a mission of St Bartholomew Edgbaston. A new red brick and red terracotta decorated gothic church by J A

Chatwin was consecrated in 1898 on a site given by Lord Calthorpe. There is an apsidal baptistery and a north-west spired tower in which hangs a set of 8 tubular bells almost certainly installed

by Harrington, Latham & Co of Coventry in 1899. The building is Grade II Listed. The original wooden building of St Agnes, Wake Green survives here as a church hall.

Click to enlarge the images below.

Take a look - The County Ground, Edgbaston

For many people across the world the name of Edgbaston is synonymous with cricket. It is known that cricket was being played in Birmingham in the mid-18th century and was a popular sport often based around pubs and churches. By c1880 Birmingham schoolmaster, William Ansell had formed the Birmingham Association of Cricket Clubs to co-ordinate matches between local teams.

A team calling itself the Warwickshire Cricket Club was in existence in Wellesbourne, Warwickshire in 1826, but this was a grand title rather than a representative county club. Subsequently other

clubs also used the name. However, in 1882 William Ansell arranged a meeting in Coventry to discuss the formation of a proper county club, and later that year the Warwickshire County Cricket Club

was formally set up at Leamington Spa.

It was agreed, though not unanimously, to establish the county ground at Birmingham. The team initially played at Aston Lower Grounds, subsequently the home of Aston Villa FC. In 1885 this site,

a five hectare ‘meadow of rough grazing land' alongside the River Rea on the fringe of Edgbaston was given by Lord Calthorpe and initially used for a variety of sports. The first cricket

match at the County Ground took place in 1886 against the MCC. In 1902 the ground was designated one of the country's six test grounds.

Dr Harold Thwaite, president of the club unveiled the Thwaite Memorial Scoreboard to the memory of his late wife in 1950. It is one of the few distinctive features of the ground. The memorial

gates at the club were dedicated in 1952 to Harold Thwaite himself.

Major improvements to the ground were made in 1950s, again during the 1990s and more are currently planned.

Well worth a look -

The University of Birmingham

In 1825 Balsall Heath surgeon, William Sands Cox began lectures in his father's town house on Temple Row in town. He convinced fellow medics that a medical school should be established in Birmingham similar to those in London, and three years later he was instrumental in setting up the Birmingham School of Medicine, first in a new building in Brittle Street on what is now the site of Snow Hill Station, and situated from 1834 in Paradise Street on land opposite the Town Hall which was given by Cox's father.

The school became the Royal School of Medicine and Surgery in Birmingham in 1836 when William IV became its patron, so too Queen Victoria after her ascension to the throne the following year.

Students hitherto had gained practical experience at the Workhouse Infimary in Lichfield Street. However, the medical school urgently needed its own teaching hospital and in 1839 an appeal was

made to raise funds. It was so successful that sufficient money was raised within one year, not only from local benefactors but from wider afield, including a generous donation from the Dowager

Queen Adelaide. With Queen Victoria's patronage the new teaching hospital on Bath Row became The Queen's Hospital and was the first provincial teaching hospital in England.

In 1843 the medical college became by royal charter, The Queen's College. From that year the college was situated in a new purpose-built Gothic Revival building designed by Drury & Bateman,

which stood opposite the Town Hall between Paradise Street (the main entrance) and Swallow Street, where a chapel was built dedicated to St James. The college had a large lecture theatre,

laboratories, anatomical rooms, a dining hall and apartments for seventy students, and by 1855 taught not only medicine but had departments of arts, law, engineering, architecture and general

science. It was partly due to the financial cost of this rapid expansion that was to lead to the college's undoing.

The building was given a new buff-coloured terracotta and brick front in 1904. The entire building to the rear was demolished at the end of the 20th century, with the Grade II listed façade

retained and incorporated into an office and residential block, known as Queen's Chambers. Nothing now remains of the original building.

Meanwhile in 1851 the General Hospital set up its own highly successful college, first in St Paul's Square, later in Summer Lane. This was also primarily a medical college but it too had

departments of classics and mathematics. By the 1860s Queen's was floundering. There were mounting debts, bitter disputes between departments and between staff and management. In 1867 the college

was effectively closed and reopened under a new charter. The medical school and the teaching hospital were to become separate entities. The following year Sydenham College dissolved itself to

amalgamate with Queen's and the reformed college went from strength to strength.

In 1875 the Birmingham pen millionaire, Josiah Mason founded Mason Science College which was housed from of 1880 in an imposing red-brick and terracotta neo-gothic building on the site of the

present Central Library. Its science facilities were so much superior to those of Queen's College that in 1882 the departments of botany, chemistry and physiology transferred to the Science

College, followed shortly afterwards by the departments of anatomy and physics. With the transfer of the Medical School to Mason College as the Queen's Faculty of Medicine, moves were made to

incorporate the institution as a university college. As a result of an act of 1897 it became Mason University College on 1st January 1898, with Joseph Chamberlain as President of the Governors.

A small Anglican theology department remained in the Queen's College building, and this moved in 1923 to the former Bishops Croft in Somerset Road, Edgbaston, becoming the present Queen's

College. A residential block in neo-Georgian style was designed by Holland Hobbiss shortly afterwards. Hobbiss's chapel, which opened in 1947, is designed in Romanesque style and was the first

English church with an altar placed away from the east wall to allow the celebrant to stand behind it and facing the congregation. In 1970 Queen's became Britain's first ecumenical theological

college sponsored by the Church of England, the Methodist Church and (later) the United Reformed Church.

Thanks to Chamberlain's tireless advocacy the University College was granted a Royal Charter by Queen Victoria in 1900 to become the University of Birmingham. The Calthorpe family offered some 10

hectares of land in Edgbaston and with the financial support of the Scottish philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie, building began on this out-of-town greenfield site. The university buildings there

were opened by Edward VII in 1909, the first red-brick university.

The original campus is arranged around the Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower, 'Old Joe', which commemorates the university's first chancellor and which is visible for miles around.

Measuring over 100m in height it is one of tallest free-standing clock towers in the world and even now is the third highest building in the Birmingham.

Unusually, the tower was built from the inside without scaffolding - and probably as a result of that it needed repointing by 1914. The clock made J B Joyce of Whitchurch was paid for by the main builder of the university Thomas Rowbotham; the dials measure 17' 6" in diameter. Rowbotham also paid for the five chiming bells cast by Taylor of Loughborough. They were rehung by Taylor's in 1981.

The campus was designed by the London partnership of Aston Webb and Ingress Bell, particularly known in Birmingham for the design of the Victoria Law Courts. The Chancellor's Court was designed in a D-shape with the central Great Hall opposite Old Joe flanked by 6 domed blocks on the curved side. The plan was never completed. However, on the centenary of the opening of the Aston Webb building and the Edgbaston Campus by Edward VII in 1909, planning approval was given for a sixth dome to complete the symmetry. Designed to modern standares but in sympathy with the original buildings, it will house the University's music department.

The Guild of Students building designed by Holland W Hobbiss and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts by Robert Atkinson were built just before the Second World War. The art gallery at the Barber is

well worth containing as it does works by many well-known artists including Bellini, Botticelli, Degas, Delacroix, Gainsborough, Gauguin, Holbein, Ingres, Magritte, Manet, Matisse, Monet,

Picasso, Poussin, Rembrandt, Rodin, Rossetti, Rubens, Veronese, Turner, Van Dyck, van Gogh and Whistler.

After the Second World War properties and land was bought from the Calthorpe estate to build a residential area around an artificial lake at The Vale. However, the first hall was not opened until

1964. Extensive redevelopment has recently taken place on this site.

During the 1960s the university went through a period of considerable expansion and a new plan of building was drawn up for the campus which effectively ignored Webb & Bell's original design.

Sir Hugh Casson and Neville Conder placed new buildings so as to create semi-enclosed squares. While Casson & Conder designed the Refectory and Staff House, other buildings were by a number

of different architects and very much in the style of the period.

Well worth a look is the Lapworth Museum in the Aston Webb Building with its fine collection of some 250 000 specimens of fossils and rocks, the best in the Midlands. Charles

Lapworth was the first Professor of Geology at Mason College and the Museum has his extensive archive of influential research spanning some 50 years. It also houses William Murdocks' mineral

collection.

Also well worth a look is Winterbourne Botanic Garden, 2.5 hectares designed in Edwardian Arts & Crafts style and Grade II Listed. The house was built in 1903 for the

industrialist John Nettlefold of Guest, Keen & Nettlefold and designed in the style of a country estate. Margaret Nettlefold designed the garden after the style of Gertrude Jekyll. The last

private occupant was John MacDonald Nicolson who developed new areas in the garden. Nicolson died in 1944 and bequeathed both house and garden to the University.

A number of other significant domestic buildings in the area have also been bought by the university for its own use.

In 1973 University station was opened on the Cross-City Line to serve the university; it is due to be rebuilt in time for the Commonwealth Games at Birmingham in 2022. Birmingham is the only

British university to have its own station. The student population now numbers some 30,000.

University of Birmingham Gallery

The photographs below were taken by Robert Darlaston in the 1990s. They are ‘All Rights Reserved’ and are used with his kind permission. The accompanying text is that of Robert Darlaston and is used with thanks.

Queen Elizabeth Hospital and the University Medical School

When the University's science and engineering departments moved to Edgbaston after 1909 the Medical School remained in the old Mason Science College. After the First World War plans were drawn up to expands hospital provision for Birmingham. The General Hospital and Queen's Hospital amalgamated in 1926 and a new hospital in Edgbaston was planned to be built adjacent to a new Medical School building. This was opened in 1939 by King George VI & Queen Elizabeth and named after the latter.

Work on a new hospital building began in 2006 west of the site to replace much of the current buildings as well as Selly Oak Hospital. The new hospital opened to patients in 2010

Another notable Edgbaston foundation also started life elsewhere. The Guild of the Holy Cross founded in 1392 effectively became King Edward's School as a result of the dissolution of the chantries in 1545. (See Birmingham.)

Standing on the south side of New Street between the High Street and Stephenson Place, the large timber-framed Guild Hall was replaced in 1707 by a neo-classical building, which was itself replaced in 1835 by a gothic building by Charles Barry, architect of the Houses of Parliament. Barry's building was demolished in 1936 and the new school, designed by Holland Hobbiss, opened four years later on the present site in Edgbaston Park Road.

Hobbiss was also responsible for building the new school's chapel. He removed the upper corridor of Barry's New Street building which linked the school and library and rebuilt it clad with brick on the new site. The chapel opened in 1952 on the occasion of the school's 400th anniversary.

King Edward's High School for Girls, founded in 1883 in the New Street building, took adjacent premises also in 1940.

William Dargue 22.03.2009/ 16.11.2020

For 19th-century Ordnance Survey maps of Birmingham go to British History Online.

See http://www.british-history.ac.uk/mapsheet.aspx?sheetid=10091&compid=55193.

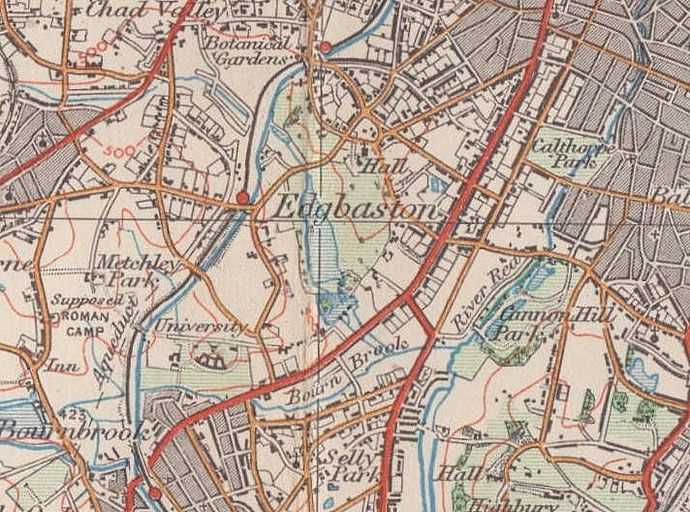

Map below reproduced from Andrew Rowbottom’s website of Old Ordnance Survey maps Popular Edition, Birmingham 1921. Click the map to link to that website.