William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

Digbeth

B5 - Grid reference SP076864

Dygbath/ Dyghbath: first record 1533

Digbeth is the name of the road north of the Rea crossing, which runs up to the Bull Ring. It subsequently also became the name of the district around the road. From at least the 12th century the market town of Birmingham was clustered around the Bull Ring on the sandstone ridge overlooking the Rea valley.

Digbeth was part of an important regional route which brought travellers and trade from towns to the east, notably Coventry, the pre-eminent Warwickshire town at that time. Other roads joined the Coventry Road below Camp Hill, from Alcester, from Stratford (for London) and from Warwick, the county town.

But travellers had to negotiate the floodplain of the River Rea to get to Birmingham. There was a ford here probably from Anglo-Saxon times, but at some medieval date this was supplemented by a

bridge, almost certainly built by one of the de Birmingham family. This was done to enable better access to the Bull Ring market, for the river flooded frequently in winter and at best the

valley was wide and marshy. As lords of the manor, the family profited from tolls paid by market traders from outside the borough. Also at some point a raised causeway was built to the bridge.

The meaning is of the placename is not clear. It seems to include the Anglo-Saxon word dic. In Old and Middle English, as in modern English, the word 'dyke' can either mean an

artificially-dug ditch or the embankment made alongside the ditch. By the 16th century there were watermills on each side of Digbeth, leats had been made across the road, and the course of the

river had been altered. The reference to a dyke may be to any one of these features, or to the causeway which led to the bridge.

Baeth was the same word used by the Anglo-Saxons to describe a Roman bath, though there is no Roman connection here. It may be that the placename means 'dyke pools' ie. pools at the

side of the causeway, though the implication of the word is related to bathing or bathing. However, paeth was the Old English word for 'path' and sometimes for 'course' as in

watercourse. Perhaps the name may best be interpreted as 'dyke path'.

Early industry

From the Middle Ages Digbeth became Birmingham's first industrial district, a time when the sounds and smells of the leather tanneries and the iron foundries filled the air (See Deritend). In 1588 William Smith wrote in his Particular Description of England:

Bromicham (commonly called Bermicham) is a proper town, with a high steple spyre, where a great store of knyves are made, ffor almost all the townes men are cutlers, or smithes.

By Tudor times there were perhaps two hundred houses in the town of Birmingham squeezed into a fairly small area. The town was centred on the Bull Ring and comprised the streets Digbeth and Deritend in the valley of the Rea, and on higher ground, Edgbaston Street, High Street, Moor Street and the lower end of New Street. All the buildings would have been timber-framed, but only the Old Crown in Deritend and the more typical Golden Lion in Cannon Hill Park now survive.

Industry and ostentatious housing were always close neighbours in this small town. By 1663 iron master John Jennens owned a very large Queen Anne-style house on the High Street and paid tax on

twenty-five hearths, while less then a quarter of mile down the hill in Digbeth there were as many as a hundred smithies belching out smoke. The lower parts of the town, Digbeth and Deritend

became increasingly working-class and industrial. As early as 1586 William Camden had written:

Bremicham, swarming with inhabitants, and echoing with the noise of Anvils, for here are great numbers of Smiths. The lower part is very watery. The upper rises with abundance of handsome buildings.

The tanyards and the foundries, and by the 1960s and 70s the residential population had gone, but this remained a thriving industrial area close to the City Centre. In the 21st century

redevelopment in this area has focussed on it becoming part of the expanded City Centre with a new mixed-use area due to replace the relocated Wholesale Market, hotels and residential on the

corner of Park street and Digbeth and extensive development as a consequence of the HS2 railway station at Curzon Street due to open in 2030.

The Battle of Birmingham 1643

During the Civil War the Battle of Birmingham was fought up into the town through Digbeth on Easter Monday 3 April 1643. A contemporary account gives a description of the events:

It was about three of the clocke on Munday in the afternoon, he [Prince Rupert] had with neere two thousand horse and foot set against the towne, playing with his ordnance, and endeavouring to force his way, with foote and horse, were twice beaten off with our musqueteers at the entrance of Derrington [Deritend], at which many of their men fell, the townes-men held them in play above an houre, we had not above one hundred and fourtie musquets and having many entrances into the towne they were many too few.

A Troope of horse of Master Perkes commanded by Captaine Greaves being in the Towne, not fit for that service, made escape when the adversaries began to incompasse the Towne, and force the waies over the meadows, and fired the Towne in two places, and so by incompassing them that did defend the out-worke, caused them to draw inward, to other workes there in Digboth, which worke they defended to the adversaries losse, but being the enemy brake in at the Millone [Mill Lane] they were forced to leave that worke also, and so put to shift for themselves, with breaking through houses, over garden waies, escaped over hedges and boggy medowes, and hiding their arms, saved most of them, the enemy killed none, some with their armes defended themselves stoutly till death.

They pursued the rest in fields and lanes, cutting and most barbarously mangling naked men to the number of fifteen men, one woman, another being shot, and many hurt, many men sore wounded, and

Mr. Tillam the surgeon standing in his dore to entertaine them, was most cruelly shot, having his leg and thigh bones broken.

They pillaged the Towne generally, their own friends sped worst, and on tuesday morning set fire in diverse places of the Towne, and have burnt neere a hundred dwellings, many other fires they

kindled, but they did not burne, they left kindled matches with gunpowder also in other places, intending nothing lesse then utterly to destroy the Towne, but by Gods providence they whose hurt

they chiefly intended by Gods hand is much prevented.

The Cavaliers have lost thirty men at least, of which there be three or foure chiefe men Earles and Lords, thirty are said to be buried and many carried away wounded.

Edited

Birmingham casualties were slight; only fourteen townsfolk were killed and some of these were royalist sympathisers. Casualties among the Royalist troops were heaviest with some thirty dead; two cartloads of bodies were carried away for burial elsewhere. In 1815 workmen digging in a garden in Floodgate Street discovered the skeleton of a soldier. He was wearing a military helmet of the Civil War period and may have been a Royalist buried in the ditch where he fell. He is likely to have been a German or Irish mercenary buried by his own side, as an English casualty local or otherwise would likely have been buried in the churchyard of St Martin's.

19th-century Digbeth

In 1837 Eliezer Edwards came from Kent as a young journalist to work on the Birmingham Daily Mail. In his book of personal recollections, First Impressions, Edwards describes his arrival in the town.

On . . . until at length the coachman, as the sun declines to the west, points out, amid a gloomy cloud in front of us, the dim outlines of the steeples and factory chimneys of Birmingham.

On still; down the wide open roadway of Deritend; past the many-gabled 'Old Crown House;' through the only really picturesque street in Birmingham - Digbeth; up the Bull Ring, the guard merrily

trolling out upon the bugle, 'See the Conquering Hero Comes;' round the corner into New Street where we pull up - the horses covered with foam - at the doors of 'The Swan.'

(The Swan was a coaching inn at the junction of the High Street with New Street.)

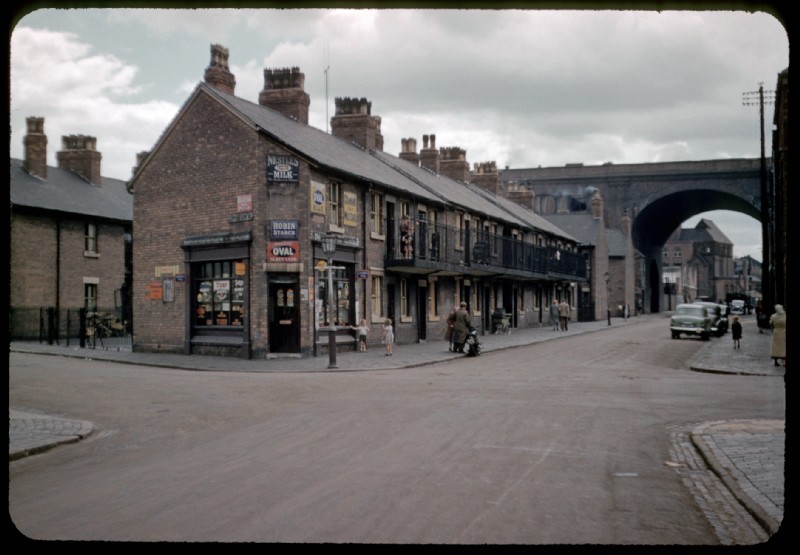

Edwards' description of Digbeth as picturesque is interesting. This district on the Birmingham side of the River Rea had been a hive of industry from the Middle Ages, and must surely have been smelly and smoky in Edwards' time.

However, on Digbeth High Street itself there were many 'quaint' timber-framed buildings some of which had been fronted with handsome brick facades in Georgian times. By the end of the 19th century when Edwards was recalling his youth, all had been demolished and replaced, with the exception of the Old Crown (See Deritend) and the Golden Lion. The latter was an early 16th-century timber-framed house which was to be demolished for road-widening. After public protests the house was dismantled and re-erected by the City Council in Cannon Hill Park in 1911 where it still stands.

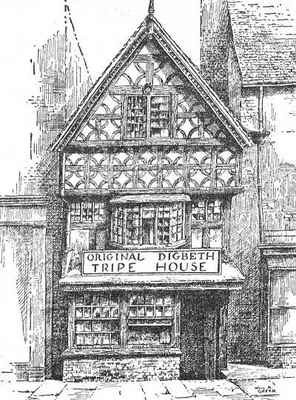

Right: The Old Tripe House, long since demolished. Drawing by William Albert Green c1930 used by with the kind permission of his son, E W Green

By the time Edwards was writing in 1877, Digbeth had become one of the poorest areas in Birmingham. Poor quality houses, many of them in courts of back-to-back tearraces, were interpersed with industry. Another journalist, J Cuming Walters described a series of Scenes in Slum-land in 1901 in The Birmingham Daily Gazette:

Court 2 Milk Street:

Its state can only be described as awful; an abomination. The unpaved, ill-drained yard was at the time of our visit half-full of water. The outhouses were disgusting. The rain was running off the roof in one part and down the wall onto a broken shed. It then trickled down and formed a filthy slop in front of a man's door.

A wash house in the corner seemed not to have been used for years, and was obviously unusable even if anyone wished to go there. It was broken down, a picture of neglect and dirt.

We entered one house, with scarcely a whole window to be seen in it, and examined the room downstairs and two rooms upstairs. The place seemed mangy and mouldy. The rotting and darkened staircase was an atrocity. It was difficult to find the way up, and hard to avoid tumbling headlong down.

The bedroom floor shook and creaked with the weight of a person walking on it . . . in these loathsome dens human beings were expected to reside, and pay 4s. or 5s. [shillings] a week for their accommodation.

The lower part of the district, built along the floodplain of the River Rea, was also prone to flash floods. Serious flooding in the lower parts of the town was recorded in 1830, 1852, 1861, and

1875. The floods affected those people least able to cope, those living in inadequate housing in the poorest parts of the town who were inundated not only with floodwater, but with industrial

pollution and human waste, as the River Rea by this time was little better than an open sewer.

Many poor quality houses were demolished when the south side of Digbeth High Street was widened again in the mid-1950s. There was further demolition during the next 10-15 years when people were

moved out of inadequate housing and the district was redefined as an industrial zone.

See also Deritend and The Bull Ring.

William Dargue 01.08.2010/ 15.11.2020