William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

The Bull Ring

B5 - Grid reference SP072865

le Bulrynge: first record 1552, The Bull Ring 18th century, Bullring 2000

The market in the Bull Ring has played a crucial role in the development of Birmingham from the 12th century until the present day. The most obvious feature here is the church of St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring.

In front of St Martin's Church was a roughly triangular open space. From at least the 16th century this was the Corn Cheaping. Deriving from the Old English ceapan meaning 'to buy', the

name meant 'corn market'. Part of it was known as the Bull Ring, a name which probably refers to bull-baiting. The practice in this country dates from Roman times, but it became especially

popular from around 1200. Most towns had a bull ring: it is argued whether this described the place, the arena (cf. boxing ring) or the metal ring to which a bull was tethered. The bull was set

on by dogs with spectators betting upon the outcome. The sport was enjoyed at all levels of society: Queen Elizabeth I was a particular enthusiast. It was popularly believed that baiting a bull

before slaughter tenderised the meat. The practice was banned by Parliament in 1835.

Birmingham's first historian, William Hutton writing in 1781 explained the origin of the name a little differently:

A John Cooper, the same person who stands in the list of donors in St. Martin's church, and who, I apprehend, lived about two hundred and fifty years ago, at the Talbot, now No. 20, in the

High-street . . . this John Cooper, for some services rendered to the lord of the manor, obtained three privileges,

- That of regulating the goodness and price of beer,

consequently he stands in the front of the whole liquid race of high tasters;

- that he should, whenever he pleased, beat a bull in the Bull-ring, whence arises the name;

- and, that he should be allowed interment in the south porch of St. Martin's church.

His memory ought to be transmitted with honor, to posterity, for promoting the harmony of his neighbourhood, but he ought to have been buried in a dunghill, for punishing an innocent animal.

Birmingham Market Charter 1166

The Bull Ring as a market place may well have originated with the charter granted in 1166 by Henry II to the lord of the manor, Peter de Birmingham.

Henry, King of England and Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine and Duke of Anjou to Archbishops, Bishops, Earls, Barons, Justices, Sheriffs, Ministers and all his faithful French and English of all England, Greetings.

Know that I have given and granted to Peter FitzWilliam the Sewer of Dudesley [ie. steward of the Lord of Dudley] in fee and inheritance and to his heirs that he may have a market on Thursdays at his Castle of Burmingeham with thol [tolls] and theam, and soc and sac and infangenethel [feudal rights as lord of the manor, including the right to levy tolls from traders coming into the town] and with all liberties and free customs.

Wherefore I will and firmly command that the same Peter and his heirs shall have a market at the aforesaid castle freely and quietly and honourably on the day aforesaid. Gervase Pagnell [Lord of Dudley and tenant-in-chief over Peter de Birmingham] granted this same to him in my presence.

Witnesses: William Malet the Sewer, John the Marshall, William de Beauchamp, Geoffrey de Ver, Hugh de Perreres, Walter de Dunstanvill. At Fekiha [Feckenham?]

(The original is in Latin.)

Peter's 'castle' was not a castle as such, but rather the moated manor house on the former site of the Wholesale Market in Moat Lane, Digbeth. It may be that a market had already developed here

and that the charter confirmed to him the right to take tolls every Thursday at his 'castle'. From Peter's point of view the issue was that only outsiders had to pay tolls; Birmingham townspeople

did not. Merchants and traders were thus encouraged to live in the borough of Birmingham and so pay rent to the lord at a rate many times greater than he would get from renting the land for

agriculture. All over England medieval lords began to set up markets at this time, but Peter's was the earliest market charter in Warwickshire and on the Birmingham plateau. The charter was

confirmed by Richard I for Peter's son, William now at his 'town', not at his 'castle', of Birmingham. The king was raising funds to finance an imminent crusade to the Holy Land.

It is likely that either Peter or William had now laid out Birmingham as a new town with building plots for rent, and that the High Street end of New Street dates from this time. This may have

been the first time that there was a 'proper' village round a village green where the market took place. (Before this 'Birmingham' would have been an area of scattered settlements rather than a

nucleated village.)

Birmingham Fair

Fairs were important occasions both commercially and socially. They drew large numbers of people from the local area as well as from further afield and enabled commerce to be conducted between

merchants. In 1250 Henry III granted William de Bermingham the right to hold a four-day fair starting on the Eve of the Feast of the Ascension (Ascension Day is 40 days after Easter). The

following year permission was also given to hold a two-day fair beginning on the Eve of the Feast of St John the Baptist, 24 June. The dates were later found to be too close together and by 1752

the fairs had been moved to Michaelmas, 29 September when half-yearly rents were due, and to Whit Tuesday, seven weeks after Easter, or two weeks after Whitsun (Pentecost) if Easter fell early.

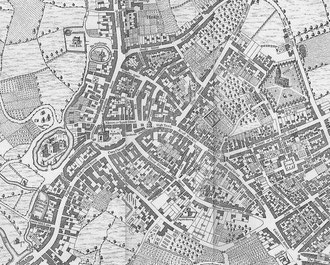

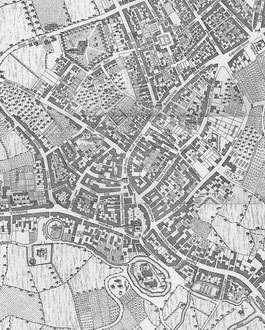

The map (part) below was made by William Westley in 1731 and is the first map of the town. Westley oriented his map with North on the right-hand side of the map. The second map has been turned following the modern convention so that North is roughly at the top. Click to enlarge the maps.

Westley's map shows the moated manor house to the south of St Martin's Church, Mercer Street across the west side of the church, Corn Cheaping across the east end, the two streets converging north of the church to form a triangular market area. By 1731 the open space had been encroached on, initially by temporary stalls being made into permanent ones, and later gradually replaced by full-scale buildings. The north-eastern end of the triangle was known as The Shambles. The word derives from shameles, a Middle English term effectively meaning a 'market stall' but later used specifically with reference to a row of butchers' shops. The animals at that time would have been slaughtered on site. By the 1700s Mercer Street was known as Spicer Street, later Spiceal Street. A spicer in medieval parlance was a dealer in spices, and more generally a grocer.

By 1801 Birmingham's Street Commissioners began to buy and demolish the houses and shops encroaching on the open space around St Martin's Church and to regularise all market activity here. Within

ten years the area had been cleared and all the buildings along The Shambles, and Corn Cheaping had gone. In order to develop the Bull Ring primarily into retail market for the town, the

wholesale markets were moved elsewhere: livestock from 1817 and fruit and vegetables from 1883 to the purpose-built Smithfield Market, the corn market to a new Corn Exchange in Carrs Lane in

1848.

Where Spiceal Street and Corn Cheaping met the High Street (or High Town) stood the High Cross. Also known as the Old Cross to distinguish it from the Welsh Cross, a two-storey

building was erected here in 1702 with the pillared ground floor open for covered trading. William Hutton writing in 1783 described it as,

the first upon that spot, ever honoured with a roof: the under part was found a useful shelter for the market-people. The room over it was designed for the court leet, and other public business, which during the residence of the lords upon the manor, had been transacted in one of their detached apartments.

The Old Cross or Market Cross, which at that time was reckoned as the centre of Birmingham, also earned the nickname of The Butter Cross as it became the place where farmers and their wives sold their butter, cheese and eggs. The building was demolished by 1784 to allow easier access from the High Town to the markets' area.

Birmingham's market day had been Thursday from at least 1166 when Henry II granted the market charter to Peter de Birmingham. However, such was the growth of the town during the 18th century that

some markets were held on other days besides. This is Charles Pye, writing in 1818:

Although there is not any shelter for the country people, yet in the most stormy weather this town is abundantly supplied with provisions of all kinds, every Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. This being the grand mart, the fertile vale of Evesham pours forth its fruit and vegetables in great profusion; and as auxiliaries, the vicinity of Tamworth and also of Lichfield send hither great quantities; in short, whatever provisions of a good quality are brought here, the market is never overstocked.

Seventy years later, Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham reckoned that

Tuesday and Saturday besides [Thursday] are now not enough; in fact, every day may be called market day.

The Market Hall

With the Bull Ring area cleared of encroachments and the relocating of the wholesale markets in hand, the Street Commissioners laid plans to build an indoor market hall. The project was to be

self-financing by the sale of land adjacent to the site which lay north-west of St Martin's Church. Designed in a neo-classical style by Charles Edge the hall was built by 1835. This was an

imposing building, whose principal entrances comprised tall round arches flanked by large Doric columns. The hall was a very large building some 365 feet long, 180 feet wide and 60 feet tall

(112m x 5m x 18.5m) with room for 600 stalls, the roof held up internally by two rows of slender cast-iron columns. It was more than twice the size of the Town Hall which Edge was also involved

in building and was described in The Penny Magazine 1835 by the Society for the Distribution of Useful Knowledge as 'one of the finest structures of the kind in the kingdom'. Lit by gas,

trading in the hall was able to continue into the hours of darkness, a boon especially during the winter months.

The Market Hall was gutted in 1940 during the Second World War by a German incendiary bomb, but the walls remained standing and the building left unrepaired until it was demolished in the early

1960s when the Bull Ring Shopping Centre was built.

Click on the images below to enlarge.

The Bull Ring Shopping Centre

During World War 2 Birmingham was the most heavily bombed city in the country outside London. The City Council after the war was faced with a massive amount of reconstruction across the city but also in the City Centre.

The area round the Bull Ring was to be completely rebuilt. The open market was to be retained north-west of St Martin's Church, while the Market Hall was to be replaced by the country's first indoor shopping mall with the indoor retail market underneath and indoor parking for 500 cars. This would be linked via a wide enclosed footbridge across the Inner Ring Road, Smallbrook Ringway to the indoor Birmingam Shopping Centre above New Street Station, later known as The Pallasades, now the known as Grand Central.

The Government stipulated that the opportunity should be taken here to separate people and traffic following the recommendations of Professor Colin Buchanan's Traffic in Towns of 1963. A new landmark building would be the cylindrical Rotunda.

The outdoor market with 150 stalls was opened first in 1962; Prince Philip officially opened the indoor Bull Ring shopping centre in 1964. The whole project was completed by 1967, was widely praised and so popular that it drew complaints from shops elsewhere in the City Centre that it was draining their trade.

However, the subjugation of pedestrians to cars, which was the opposite of what Buchanan had proposed but which was cheaper to implement, became increasingly unpopular. And the concrete buildings, which had little external attraction, had weathered badly.

By the 1980s all the main high-street stores had all moved out of the declining Bull Ring Centre and towards the end of the decade moves were again being made to redevelop the site.

Bullring

The City Council's brief was to create a wide pedestrian street, roughly following the route of the old Spiceal Street, from the High Street to St Martin's Church, in front of which there would be an open square. The project was to cover a rather larger area than its predecessor and included the renovation of Moor Street Station and the demolition of the Rotunda. The latter proposal raised such a popular furore that the building was Listed as a Birmingham icon and has since been renovated for use as apartments.

Demolition of the old shopping centre began in 2000 and three years later the new indoor shopping centre, known as 'Bullring' opened. All the markets had moved to Edgbaston Street, the Indoor Market at the corner of Pershore Street, the Rag Market and the Open Market south of St Martin's Church. The open space, St Martin's Square, around three sides of the church takes advantage of the rising ground to the High Street and effectively takes the form of an arena with the church centre stage.

The bronze statue of Admiral Lord Nelson by Richard Westmacott was Birmingham's first public monument and the first to the great national hero to be erected in Britain. Nelson

visited Birmingham in 1802 to great acclaim after his victories at the Battle of the Nile and Copenhagen. He visited Matthew Boulton and the Soho Manufactory to arrange the striking of the medal

for the Battle of the Nile. The statue, which was paid for by public subscription, has now been replaced close to its original 1809 site and overlooks St Martin's Square.

Well worth a visit - Bullring shopping centre comprises the East and West Malls on several levels which are linked underneath the pedestrian walkway. The external facades of the

malls are designed in a vague post-modern neo-classical style and faced with warm yellowish stone and the walkway is bordered with open-air cafes and restaurants. Guarding the entrance to the

West Mall is a massive bronze bull by sculptor Laurence Broderick which must surely now be the most photographed location in Birmingham.

The Debenham's department store takes up the west end of the site while at the east end the controversial Selfridges department store is difficult to describe other than as a giant slug covered with 15,000 aluminium discs. Contrasting dramatically with the neo-gothic of St Martin's Church, the Selfridges building is a distinctive and unusual landmark in the same way as the Market Hall and the Rotunda were in their time. The Bullring is one of Europe's largest city centre shopping malls and attracts over 30 million visits a year.

Well worth a visit - The Markets

Demolition of the old shopping centre began in 2000 and the market traders, not without protest, moved temporarily to the Rag Market in

Edgbaston Street. Three years later the new indoor shopping centre, known as 'Bullring' opened. All the markets had moved to Edgbaston Street, the Indoor Market at the corner of Pershore Street,

the Rag Market and the Open Market south of St Martin's Church. The open space, St Martin's Square, around three sides of the church takes advantage of the rising ground to the High Street and

effectively takes the form of an arena with the church centre stage.

Click to enlarge the images below.

St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring

Well worth a visit - St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring, a Grade II* Listed building, is known as 'the Mother Church of Birmingham'. It is not known whether there was a church here in Anglo-Saxon times. When the new town of Birmingham was developed at the time of the Market Charter it is possible that Peter de Birmingham also moved his manor house to the Moat Lane site and built St Martin's as a new church close by.

During the 1873 restoration evidence was found of the 12th-century building. Although the earliest recorded mention is 1263, it is fairly certain that a small church existed here at the time of the Market Charter; some ancient stonework survives rebuilt into the walls of the Guild Chapel.

The presumed earlier building was replaced by a new church of local red sandstone at the end of 13th century by one of the de Birmingham family.

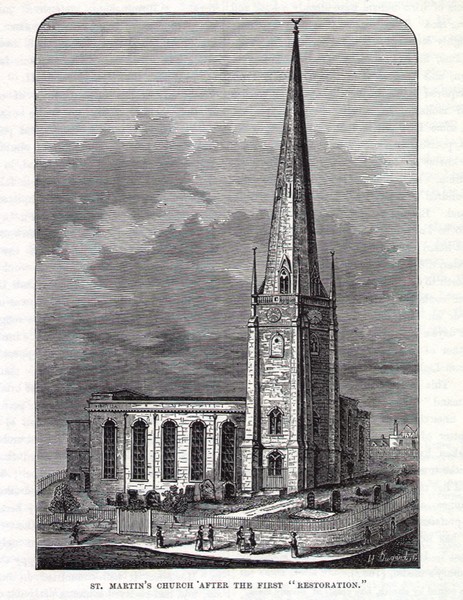

By 1690 the sandstone was badly worn and, but for the spire, was then encased in three layers of brick in a neo-classical style. The spire itself was rebuilt in 1781 in stone by John Chesshire

when internal galleries were also added. In the mid-19th century the rector, Dr John Miller launched an appeal to restore the church. Funds were not forthcoming and only the tower and spire were

restored, the final stone being placed in the presence of Prince Albert in 1855.

A restoration or a rebuilding?

In 1872 the rector, Dr William Wilkinson began to raise funds for a complete rebuilding, and although only half the money had been raised by 1873, the whole church, except for the tower and spire, was taken down to be the rebuilt by the Birmingham architect, J A Chatwin. The avowed intention had been to restore the church to what was thought to have been its gothic original, a stone church in early 14th-century decorated style. Chatwin expressed the wish to preserve what he could of the medieval building. However, the structure was too badly decayed: the ends of the chancel beams were rotten and gallery pillars were built without foundations and close to crumbling vaults. Careful demolition ensured that as much as possible was learnt about the church before evidence was destroyed and the new choir stalls were made of wood salvaged from the medieval roof timbers.

The hammer-beam roof resembles that of Westminster Hall which Chatwin had worked on under Barry and Pugin. The barrel-vaulted chancel roof rests on corbels carved as minstrels and there is a good floor of Minton tiles.

Chatwin's sandstone reredos stretches across the full width of the east window. Made up of seven panels under elaborate gothic arches with 45 figures in alabaster, it shows scenes of Christ entering Jerusalem, Christ casting out the money-lenders, the Last Supper, the Garden of Gethsemane, the Betrayal by Judas Iscariot. Figures of the Apostles and of Moses and Aaron appear along the top and sides.

The new church, which was reconsecrated on 20 July 1875 by Bishop Henry Philpott of Worcester, was held to be a fitting mother-church for the town. However, the editor of The Birmingham Daily Post, J T Bunce was realistic about what had been done:

Properly speaking, there has been no restoration at all, but an absolute demolition of an inconvenient and unsightly building, destitute of any single feature of interest, and the substitution for it of a new and larger church, on a different plan, and in a different style of architecture. The fact that the word 'restoration' has been adopted and accepted as properly describing such a work affords a curious illustration of the very wide meaning which has now become attached to that word.

Badly worn effigies inside the church are early members of de Birmingham family: Sir John de Birmingham c1400, Sir William de Birmingham c1325, Sir Fulk de Birmingham c1370 all of whom must have been buried inside the building. There is also an effigy of an unknown priest c1500.

The medieval-style stone statues on the north and west fronts were designed by Chatwin and sculpted by Robert Bridgeman's of Lichfield. They depict King Richard I in commemoration of his visit

c1189 confirming the market charter, and St Martin of Tours giving his cloak to a beggar. Above the south porch a series of six roundels following the curve of the arch show scenes from the life

of St Martin with a statue Saint Martin in bishop's garb at the apex. The external stonework was cleaned during the redevelopment of the Bull Ring 2002-2003.

During the Second World War a German bomb damage caused serious damage at the west end of the building on 10 April 1941. All the Victorian stained glass was destroyed with the exception of

Burne-Jones' south transept window which had been stored in a place of safety that same day by W E Barnes, the Bishop of Birmingham, despite the decision of the parochial church council that the

window should not be removed as it could be replaced if damaged. The war damage was restored by 1957 and a new parish hall was also added designed by Chatwin's son, P B Chatwin, also in red

sandstone but in a sort of Tudor style, a little incongruous with the unity of the rest of the building.

There were four bells here in 1552, six in 1682 and eight in 1751. When St Philip's increased theirs to a 10-bell ring, St Martin's brought theirs up to 12. A number of the bells were recast and rehung over the years, all 12 being recast in 1928 by Mears & Stainbank of the Whitechapel foundry. The rivalry with St Philip's continued, and in 1991 this became the only church in the world with 16 bells capable of English change-ringing. This ring cast by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry has the heaviest full-circle tenor in the diocese weighing 39cwt 3qr 19st. St Martin's is the mother-church of the Birmingham diocesan guild, St Martin's Guild of Church Bellringers for the Diocese of Birmingham which was established in 1755.

Burials must have taken place here from the Middle Ages; the burial registers date from 1554. As the only church of a rapidly expanding parish, the graveyard was extremely full by the late 18th

century and extended. William Hutton in 1783 described the problem with his usual wit:

From the eminence upon which the High-street stands, proceeds a steep, and regular descent into Moor-street, Digbeth, down Spiceal-street, Lee's-lane, and Worcester-street. This descent is broken only by the church-yard; which, through a long course of internment, for ages, is augmented into a considerable hill, chiefly composed of the refuse of life.

We may, therefore, safely remark, in this place, the dead are raised up. Nor shall we be surprised at the rapid growth of the hill, when we consider this little point of land was alone that hungry grave which devoured the whole inhabitants, during the long ages of existence, till the year 1715, when St. Philip's was opened.

The curious observer will easily discover, the fabric has lost that symmetry which should ever attend architecture, by the growth of the soil about it, causing a low appearance in the building, so that instead of the church burying the dead, the dead would, in time, have buried the church.

The graveyard was closed in 1848 when Park Street Burial Ground opened, except for burials in family graves which continued until 1915. The churchyard was laid out 1880 as a public park. The

crypt was excavated by Birmingham Museum 1974 and found to be two thirds full of disarticulated human bones.

St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring - Gallery

William Dargue 15.10.2008/ 09.11.2020