William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

Birmingham City Centre

formerly in Warwickshire - a Domesday manor and ancient parish

B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 - Grid reference SP069869

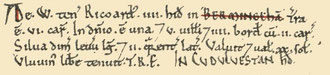

Bermingeha: first record in the Domesday Book 1086

For other City Centre places, see

The Bull Ring, The Business District, Cheapside, The Chinese Quarter, Colborne Fields, The Convention Quarter, Dale End, Deritend, Digbeth, Dudwalls, Eastside, Easy Hill, The Froggery, Gosta Green, High Town, Holloway Head, Holme Park, The Horsefair, The Inkleys, The Irish Quarter, The Italian Quarter, The Jewellery Quarter, Little Park, Paradise.

Birmingham skyline from above Centenary Square: the cylindrical Rotunda far right, Hall of Memory to the fore, black and the red rectilinear Copthorne Hotel behind with the Central Library in the centre. The clock tower of the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery and columns of the classical Town Hall are visible, as is Baskerville House, scaffolded, to the left. The tallest building visible is the tower of NatWest bank.

Image reproduced from Wikipedia - see Acknowledgements. Taken by Andy G from the Roue De Paris in 2004, revised by G-Man. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this image under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.

For a suggested walk across part of the City Centre which takes in a slice of Birmingham's history and interesting buildings, see further down this page:

- A Walk up New Street from the Markets to Centenary Square -

The origin of the City's placename

The name of Birmingham is now applied equally to the City Centre as to the whole of the Metropolitan Borough of the City of Birmingham. In the document as a whole, it usually means the latter; but in this article it generally refers to what we now call the City Centre, or to the medieval borough which effectively preceded it, the area now popularly known as Town.

The city's name translates from the Old English Beorma-ing-ham as 'Beorma's people's village'. These people may have been followers of a man called Beorma (pronounced Berma) or, more

likely, a tribe or clan called the Beormings, ie. Beorma's people. Whichever, they were almost certainly people of Anglian origin who had come southwards from the east Midlands following the

valley of the Tame to settle on the lighter soils of the Birmingham sandstone ridge. It is impossible to ascertain whether a leader called Beorma founded a settlement here, or whether it was

founded by a people named after him. The name is probably best interpreted as 'the Beormings village'.

Anglo-Saxon placenames ending in -ingham are predominantly found in East Anglia, Lincolnshire and east Yorkshire with only a scattering further west. They are therefore likely be places

named early in the Anglo-Saxon settlement. Birmingham may have been so-named by the early 7th century, possibly earlier. It is highly unlikely to have been a settlement or defined land unit

before the Anglo-Saxon period.

The development of the name is interesting. Spelling until the age of printing (and even afterwards) was a haphazard affair. However, it did represent the way that people pronounced words. It can

be seen from the following list of spellings that the city's name is equally represented with Birm- variations as with Brum- spellings. The name evolved into Birmingham and also into Brummagem,

which has been contracted to Brum since Victorian times. Why the name Birmingham finally took precedence over Brummagem remains a matter of debate.

Lords of the Manor

Before 1066 many of the manors that now make up modern Birmingham belonged to Earl Edwin, the Anglo-Saxon Lord of Mercia, and were governed by Anglo-Saxon lords of the manor. As Earl Edwin was not present at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 he was allowed by the victorious William the Conqueror to keep his lands. In 1068, however, Edwin took arms against William who consequently confiscated his holdings.

William rewarded his companions at Hastings by giving them estates confiscated from Anglo-Saxon lords. Where overlords had a number of estates, the Conqueror ensured that they well spread out across the country to prevent tthem from becoming too powerful. Ansculf of Picquigny, however, acquired some thirty estates formerly belonging to Edwin which were centred on Dudley Castle. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 these estates were owned by his son, William FitzAnsculf, Baron of Dudley who owned altogether over a hundred manors in ten different counties of England.

With the exceptions of Berwood and Sheldon, all the Warwickshire manors in modern Birmingham, plus Handsworth in Staffordshire, were held from the Middle Ages by a line of overlords descended from William FitzAnsculf. He is recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086 as overlord of Aston, Birmingham, Edgbaston, Erdington, Handsworth, Little Barr, Perry and Witton.

Subsequently FitzAnsculf's overlordships passed via female lines to the Paynel family and in 1194 to de Somerys. With the death of John de Somery in 1322 the overlordships were divided between his sisters: Birmingham, Little Barr, Perry and the Barony of Dudley went to Margaret, the wife of John de Sutton whose descendants as Suttons or Dudleys continued to hold the overlordship of Birmingham. Aston, Edgbaston and Handsworth went to the John de Somery's widowed sister, Joan Botetourt. She was succeeded by her son John and then by his granddaughter, Joyce Burnell. During the early 15th century the overlordship was split among various co-heirs who subsequently sold their interests. The last known overlord was Joan Beauchamp c1420. There is no further mention of the descent of the manors of Little Barr and Perry.

In the time of King Edward the Confessor the lordship of the manor of Birmingham was in the hands of an Anglo-Saxon lord, Ulwin/ Wulfwin. By 1086 Wulfwin's manor was held by Ricoard/ Richard

presumably a Norman follower of William FitzAnsculf.

From William Richard holds 4 hides in Birmingham. Land for 6 ploughteams. In the demesne 1 hide. 5 villeins & 4 bordars with 2 ploughteams. Woodland half a league long & 2 furlongs. The value was and is 20 shillings. Wulfwin held it freely in the time of King Edward.

This was a small manor even by local standards with a population of perhaps only fifty people and a taxable value of only 20 shillings. Much of the manor was heathland of little value at that

time for agricultural use (See Birmingham Heath).

William de Birmingham, the Steward of Dudley was lord of the manor in 1153 when he was granted free warren by Henry II, and it was his son, Peter de Birmingham who was granted the town's market

charter in 1166 (See The Bull Ring.) The de Birmingham's were very likely the descendants of the Richard mentioned in the Domesday Book. The manor then

passed down through the family, though not without complication or incident, until 1539. The last of the family to be lord of the manor was Sir Edward Birmingham. He was not only in debt to the

king but had been unjustly convicted of felony as a result of the machinations of John Dudley, later the Duke of Northumberland, who had designs on the manor. In 1545 Edward VI granted Dudley the

lordship of Birmingham valued at £50, the borough, the advowson of St Martin's Church, as well as certain lands and mills in the manor. However, he did not enjoy his ill-gotten gains for long. As

a prime mover in the unsuccessful bid to install Lady Jane Grey as queen after the death of Edward death, he was found guilty of high treason under Queen Mary and executed in 1553. The

manor thus reverted to the Crown.

In 1557 the manor and manor house were bought by one Thomas Marrow of Berkswell and were passed from father to son four times until the death of Sir Samuel Marrow c1684. His five daughters sold

their interests in the manor to Thomas, Lord Archer of Umberslade in 1746. On the death of his son, Andrew in 1778 the rights passed to his daughters. The manorial rights were bought by the

Birmingham Street Commissioners under an Act of Parliament in 1812 at a cost of £5672 for the manor house and £12 500 for tolls appertaining to the market. By 1850 the manor was held by

Christopher Musgrave of Foxcoat in Sussex, the son of Anne Elizabeth Archer, the second daughter, after which date no further trace of the descent has been found. By this time there would

have been no rights of the manor remaining other than the title.

The Gallery below is a collection of images of public buildings in 18th-century Birmingham. Most were demolished in the 19th century and none now survives.

All images are from Beilby Knott & Beilby 1830 An Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Birmingham, a work now in the public domain.

Click to enlarge the images in the Gallery.

Constant change

Since the Middle Ages the centre of Birmingham has been subject to constant change, new buildings gradually replacing their predecessors. Nothing has been discovered of the Anglo-Saxon village, but evidence of medieval houses and industry has been found below ground. The only two Tudor timber-framed survivors are the Old Crown in Deritend and its near-neighbour, the Golden Lion, the latter re-erected in Cannon Hill Park.

During the great expansion of the Georgian period many of the old half-timbered buildings were demolished or faced with brick, but none of these now survive. And little remains of the newly-built

houses of the 18th century, other than some late 18th-century buildings in the Jewellery Quarter.

However, a substantial part of the Victorian city still stands - take a walk up New Street and into the Business Quarter or along Corporation Street.

Post-Second World War Birmingham is still much in evidence. Many bombed sites had to be rebuilt and the construction of the Inner Ring Road and consequent demolition of many Georgian and

Victorian buildings significantly reshaped the City Centre. There was a time during the 1960s when hapless bus travellers were constantly challenged to find where their familiar bus stop has been

relocated.

The end of the 20th century and the beginning of the present century have seen major redevelopments in the Broad Street area and the rebuilding of the 1960s Bull Ring centre, with the same

consequences for bus travellers. There has probably never been a time since the Middle Ages when parts of the present City Centre were not being built or rebuilt.

A collection of photographs of surviving Victorian buildings in the City Centre.

I Can't find Brummagem

In 1828 the Birmingham comedian, James Dobbs wrote 'I can't find Brummagem', sung to the tune 'Rob Roy McGregor O!' The words could easily be adapted for any time in Birmingham over the past 500 years.

I can't find Brummagem

Full twenty years, and more, are past

Since I left Brummagem,

But I set out for home at last,

To good old Brummagem.

But every place is altered so,

There's hardly a single place I know;

And it fills my heart with grief and woe,

For I can't find Brummagem.

As I walked down our street,

As used to be in Brummagem,

I know'd nobody I did meet;

They change their faces in Brummagem.

Poor old Spiceal Street's half gone,

And the poor old Church stands all alone,

And poor old I stand here to groan,

For I can't find Brummagem.

But 'mongst the changes we have got,

In good old Brummagem,

They've made a market of the Mott [moat]

To sell the pigs in Brummagem.

But what has brought us most ill luck,

They've filled up poor old Pudding Brook,

Where in the muck I've often stuck

Catching jackbanils [sticklebacks] near Brummagem.

But what's more melancholy still

For poor old Brummagem,

They've taken away all Newhall-hill,

Poor old Brummagem!

At Easter time, girls fair and brown,

Used to come roly-poly down,

And show'd their legs to half the town,

Oh! the good old sights of Brummagem.

Down Peck Lane I walked alone

To find out Brummagem,

There was a dungil [dungeon] down and gone!

What no rogues in Brummagem?

They've taken it to the street called Moor,

A sign that rogues they get no fewer,

The rogues won't like to go there I'm sure,

While Peck Lane's in Brummagem.

I remember one John Growse,

A buckle-maker in Brummagem;

He built himself a country house

To be out of the smoke of Brummagem;

But though John's country house stands still,

The town itself has walked up hill.

Now he lives beside a smoky mill

In the middle of the streets of Brummagem.

Amongst the changes that abound

In good old Brummagem,

May trade and happiness be found

In good old Brummagem;

And though no Newhall-hill we've got,

Nor Pudding Brook, nor any Mott,

May we always have enough to boil the pot

In good old Brummagem.

Brewing up on the cut

- A Walk up New Street from the Markets to Centenary Square -

While omitting many buildings and areas of interest in the City Centre, a walk from the markets up New Street to Centenary Square gives a flavour of the history and present state of Birmingham City Centre.

See also the Bull Ring.

A walk up New Street from the Markets to Centenary Square - The Bull Ring

Situated below the junction of the High Street and New Street, the Bull Ring has long been considered the heart of Birmingham. It has often thought to have been the village green of the

Anglo-Saxon village. However, although excavations in advance of the new Bull Ring shopping centre found evidence of a Roman-period farm in Park Street, no trace was found of an Anglo-Saxon

settlement here. There was, however, ample medieval evidence in the immediate area: traces of boundary banks and ditches, houses, cattle and a variety of industries.

From the Middle Ages roads from the west converged on the Bull Ring bringing traders from Lichfield, Stafford, Wolverhampton, Dudley, Halesowen and Worcester, and from the east travellers from Coleshill, Coventry, Warwick and Stratford, and Alcester. Clear evidence that the market charter which Peter de Birmingham bought from the king in 1166 capitalised on a promising site and provided the critical stimulus the kick-start town's economy. The markets and the area around the Bull Ring were the engines that helped to drive the trade and industry of the town from the Middle Ages until the 19th century.

The problem of the markets area was its own success. By the end of the 18th century, both wholesale and retail market traders vied with one another for space here and spilled out along the High

Street. By 1801 the Board of Street Commissioners began the demolition of the illegally encroaching houses and shops to create an an open space around St Martin's Church for the retail markets.

In 1835 the Street Commissioners opened the Market Hall, a massive neo-classical style building over 100 metres in length and almost 20m in height with accomodation for 600 stalls.

During the Second World War the hall was directly hit by a German bomb. The outer walls remained standing, but the building was left unrepaired until the early 1960s when the new Bull Ring Shopping centre was built.

After the war the area round the Bull Ring was completely rebuilt. The open market was retained north-west of St Martin's Church, but the Market Hall and the surrounding buildings were replaced

by the Bull Ring Shopping Centre, the country's first indoor shopping mall. There was a bus station and the indoor market underneath and the centre was linked via an enclosed footbridge

across the Inner Ring Road to the shopping centre above the newly-rebuilt New Street Station. The shopping centre suffered a serious decline in popularity by the early 1980s and a new development

was mooted.

The present Bullring shopping centre is designed around the open space in front of St Martin's Church and the pedestrian access to it from the High Street. Opened in 2003 the shopping centre

comprises an East and a West Mall on several levels linked underneath the pedestrian walkway. Debenham's department store takes up the west end of the site, while at the east end is the

controversial Selfridges store, a massive curving building covered with 15 000 shiny aluminium discs. While not universally admired in the city, it is a distinctive and unusual landmark.

Just below St Martin's Church in Moat Lane stood the medieval manor house. The hall stood on a moated site probably dating from the 12th century and was occupied by the de Birmingham family until

Sir Edward's departure c1545. The house was rebuilt about 1730 but demolished by the Street Commissioners in 1816 to make way for increased wholesale market space.

Click to enlarge the images in the Bull Ring Gallery below.

A walk up New Street - St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring

'The Mother Church of Birmingham' may date from the time of Peter de Birmingham's Market Charter in 1166 when he developed the 'new town' of Birmingham. A small amount of material evidence found during the rebuilding of 1873 dates the building to the 12th-century, although the earliest recorded mention is 1263.

The earlier building was replaced by a new church made of local red sandstone at the end of 13th century but by 1690 the soft stone had worn badly and, except for the spire, the whole building

was encased in brick in a neo-classical style. The spire was rebuilt in 1781.

By 1872 enough money had been raised to make a start of the restoration of the church to its gothic past. However, it was alleged by the architect, J A Chatwin that the building was in such poor

condition that, but for the tower and spire, a complete rebuild, said Chatwin, was the only option. The new church was built in 14th-century decorated gothic was reconsecrated on in 1875 by the

Bishop of Worcester.

For more information on the Church of St Martin-in-the-Bull Ring, see the Bull Ring.

A walk up New Street - The Rotunda

One of the oldest streets in Birmingham is Le (the) New Street, mentioned in a deed of 1296. The insertion of 'the' implies that this may have been a description of the recently cut street rather than its name. It may have been laid out as a more satisfactory route from the centre of the town at the Bull Ring to the junction of the Dudley Road and the Halesowen Road (now Broad Street and the Hagley Road) at what is now Victoria Square. (The route to the Birmingham markets was formerly via Pinfold Street, Dudley Street and Edgbaston Street). However, the laying out of the street would also have enabled the lord of the manor to lay out more burgage plots for rent, as the existing streets of the town were by then crammed with buildings.

At the junction of New Street with the High Street stands the Rotunda, a 20-storey cylindrical office block. Designed by James A Roberts as part of the 1960s Bull Ring development, it was completed in 1964. Its demolition was proposed at the end of the 1980s as part of the new Bull Ring redevelopment and met with widespread and successful calls for its retention. In 2000 The Rotunda was made a Grade II Listed building and subsequently refurbished as an appartment block.

On the evening of 21 November 1974 IRA terrorists exploded a bomb in the Mulberry Bush, a public house which used to be on the ground floor of the Rotunda on the side nearest to New Street

Station. Almost simultaneously another bomb was exploded at the nearby Tavern in the Town, a basement pub in New Street, now The Yard of Ale. 21 people were killed and 182 were injured, many

seriously. The innocent dead are remembered by memorial in the churchyard of St Philip's Cathedral.

A walk up New Street - A diversion along the High Street

The High Street is one of the town's original thoroughfares which, as a local and regional route, may actually predate the town itself. The High Street has had various names along its length. In

the 18th century the hill from the Bull Ring up to the junction with New Street was High Town; up to Carrs Lane was the English Market, Beast Market or Rother Market ('rother' was a medieval term

for any 'horned animals', but more usually cattle); around the junction of Bull Street was the Welsh Cross or Welch Cross where drovers brought their cattle for sale from Wales; from there to the

road out of the town was Broad Street, at the end of which was Dale End, the end of town overlooking a dale or valley where Coleshill Street headed out to Saltley, Castle Bromwich and Coleshill.

The High Street is now pedestrianised and one of Birmingham's most important shopping streets with major stores and a shopping mall, the Pavilions which was built in 1988 after the economic

recession of the 1970s.

Click to enlarge the images in the High Street Gallery below.

A walk up New Street - Lower New Street

By the beginning of the 19th century the High Street and New Street were developing as retail shopping streets. At this end of New Street by the mid-19th century there were offices, cafés and

pubs, a dentist's and an optician's practice, newspaper offices, an auctioneers & estate agent, a photographic studio, and shops selling hats and shoes, clothes, suitcases, sweets, tobacco

and cigars, household, fancy goods and furniture, haberdashery and carpets, jewellery, clocks and watches. The density and variety is repeated on the High Street and up the length of New Street.

The Big Top at the corner of New Street and the High Street completed in 1959, was Birmingham's first purpose-built shopping centre. Shops front New Street and the High Street, with arcades

taking shoppers through to Corporation Street and Union Street. Above it stands the City Centre House office block which at the time was the city's tallest. The site had been devastated by German

bombs during World War 2 and after the war was used as a circus venue, hence its name.

Other than cinema buildings there is little Art-Deco architecture in Birmingham. The former Times Furnishing store on the High Street is an exception. Designed by architects Burnett & Eprile

in 1938, it is now a Waterstones book shop.

The lower stretch of New Street up to Corporation Street was largely rebuilt before World War 2. This section of the street is completely pedestrianised, as is the High Street.

The Guild of the Holy Cross seems to have been founded by 1392 by four wealthy Birmingham men. A chantry chapel was established in St Martins-in-the-Bull Ring and two priests supported by the income of land in Birmingham and Edgbaston. The Guild was a mutual body set up to support the religious and temporal needs of its members. The prime function of the priests was to conduct masses for the souls of deceased Guild members in the chantry chapel, which was dedicated jointly to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Holy Cross, St Thomas and St Catherine. The Guild also seems to have made itself responsible for the maintenance of roads and bridges in the town.

The guild built a meeting hall on the south side of New Street which would have been a timber-framed building probably similar to the Old Crown in Deritend. When Henry VIII suppressed not only the monasteries but also religious guilds, a number of Birmingham men were able to set up a school attached to the guild. So, although the guild itself ceased to exist, the school, known as The Free School, now Kings Edward VI Grammar School, was set up in 1552 in the former guild hall. This building was replaced with a neo-classical building in 1707 which was itself replaced in 1838 with a large building Tudor gothic design by Charles Barry, architect of the Houses of Parliament. Barry's building was demolished just before the outbreak of the Second World War when the school moved to its present site in Edgbaston. The Grammar School site is now occupied by the Odeon cinema, which opened as the Paramount in 1937, and King Edward's House, also built in 1937, a large office block in a vague classical style with shops on the ground floors.

Below centre right: Now known as King Edward's School, New Street. Architect Charles Barry. Demolished. The spire in the distance (right) is Christ Church, in what is now Victoria Square - from Robert Kirkup Dent 1894 The Making of Birmingham: Being a History of the Rise and Growth of the Midland Metropolis, a work in the public domain because its copyright has expired. Picture downloaded from Wikimedia Commons with a GNU Free Documentation License.Picture uploaded by Oosoom to Wikimedia.

Below right: Image 2004 uploaded to Wikipedia by G Man and declared to be in the public domain.

A walk up New Street - New Street Station

New Street Station was officially opened in 1854. The station replaced the earlier Curzon Street stations which were considered to be too far away from the town centre. Built on 3 hectares

of the low-lying Froggery slums jointly by the London & North-Western Railway LNWR and the Midland Railway, it was actually two parallel stations with Queens Drive in between. At the

time it had the biggest single-span roof in the world at 212 feet, c65 metres. Trains from London and Liverpool entered the station through the 245 metre-long South Tunnels underneath

Moor Street; trains to Wolverhampton passed through the 700m North Tunnel.

The original entrance to the station was at the junction of Navigation Street and Lower Temple Street. At the bottom of Stephenson Street was the Queens Hotel built for the LNWR in an Italianate style by William Livock. Birmingham was, and is, a major national interchange and the hotel's success led to its enlargement in the early 1880s with further extensions in 1911 and 1917. The hotel was demolished with station in the mid-1960s.

The Midland Railway side of the station was extended in 1885 and the station has been extended and altered several times subsequently. By 1900 New Street had more trains and connections to more destinations than any other station in Britain and this is still the case. The station was hit by German bombs a number of times during World War 2 and was completely rebuilt in the late 1960s. Above the station was an innovative 4ha indoor shopping centre, now called the Pallasades, which stands on some 200 reinforced concrete columns. The centre is linked by an enclosed walkway over Smallbrook Ringway to the Bull Ring Shopping Centre. 12 below-ground platforms cater for c600 trains and c60 000 passengers a day. Another major reconstruction of the station is due to be completed by 2013.

New Street's new signal box, built by architects Bicknell & Hamilton in Navigation Street, replaced 64 manual signal boxes and covers 85 route miles. It is a noted example of Brutalist architecture and a Grade II Listed building. Stephenson Place, named after the great railway engineer who built the London line, was taken at this time as the centre of Birmingham, road distances being measured from here. (Prior to this the centre of Birmingham was reckoned as the Bull Ring, firstly at the Old Cross, and then at Nelson's statue.)

A walk up New Street - A diversion up Corporation Street

The creation of Corporation Street was an expensive and lengthy undertaking which was pushed through by the vision of Birmingham's mayor, Joseph Chamberlain. He seized the opportunity offered

provided by the Artisans and Labourers Dwellings Improvement Act of 1875 to rid the town centre of the crowded and insanitary area of slums between the High Street and New Street, and to create a

'Parisian boulevard' lined with shops and offices.

Birmingham was the first and, because of the financial implications, one of the few local authorities to take advantage of the Act. The street runs from New Street close to New Street Station for ¾ mile to Aston Street to join the road to Sutton Coldfield and Lichfield. The shopkeepers in New Street and on the High Street protested vigourously that the street would draw away their customers and the economist group on the Council complained about the unwarranted waste of public money, almost £1.5 million. The sale of leases was expected to recoup much of that and in the longer term the project was commercially a great success which opened up the centre of the town and whose impact remains to the present day.

The scheme entailed the demolition of some 600 buildings, which included the homes of nearly 17 000 residents, mostly very poor tenants. The property owners were paid for their inconvenience, but

the Artisans and Labourers Dwellings Improvement Act did not live up to its name and made no provision for councils to rehouse those displaced. It was not until the Housing of the Working Classes

Acts of 1885 and 1890 that councils were empowered to make housing available.

Demolition and rebuilding began at the New Street end of Corporation Street in 1878 and four years later had reached Old Square. However, it was not until the beginning of the 20th century that the far end of the street was completed. Towards the end of the project, Birmingham historian, Robert K Dent wrote approvingly:

Gradually the line of Corporation Street began to be built upon, fine buildings of real architectural merit taking the place of the mean and dingy houses of the eighteenth century, and as a

result of the formation of the new street the standard of shop architecture in Birmingham has been infinitely raised. One of the distinctive features of the new thoroughfare is that the buildings

in it exhibit a pleasing variety of angle, height, and architectural style, in marked contrast to the dull uniformity which prevails in some of the great thoroughfares in other

cities.

Robert K Dent 1894 The Making of Modern Birmingham

Most of the buildings were sold on 75-year leases after which time they reverted to the Council, Dent quotes Chamberlain as saying,

This will make Birmingham the richest borough in the kingdom sixty or seventy years hence. It is the only occasion for which I wish to live beyond the ordinary term of human life, in order to see the result of this improvement, and hear the blessings which will then be showered upon the Council of 1875, which had the courage to inaugurate this scheme.

One of the effects of the arrangement, together with City Council's redevelopment policies, was the demolition of buildings during the 1960s which might now have been thought worth saving. Add to this the destruction wrought by German bombs during the Second World War and Corporation Street is only half the Victorian street it was. Nonetheless, important buildings survive in the street which are well worth a look.

There is a good run of buildings on the north-west side of the street from New Street to Cherry Street most of which were built between 1880 and 1885. Above the shop fronts can be seen a variety

of styles including French Renaissance and Flemish, gothic and Ruskinian gothic. The building at the junction with New Street was named Queens Corner in commemoration of Queen Victoria's visit in

1887; a commemorative inscription can be seen high up on the corner building opposite the former Midland Bank.

Old Square was first laid out in 1697 surrounded by high-status Georgian houses. Most of them were demolished as part of the Corporation Street Improvement Scheme. With the exception of the former Lewis's department store of 1925, the Square is surrounded by 1960s development.

The central public area was refurbished in 1998 as part of the project to break through the Inner Ring Road when the elevated section of Priory Queensway was dismantled. A large relief panel of 1967 depicting the history of the Square was restored by the artist, Kenneth Budd in 1998.

A 4m-high bronze statue stands in the Square of the Birmingham comedian, Tony Hancock who was born in Southam Road, Hall Green. Created by Bruce Williams in 1996 the statue is pierced throughout with glass beads to give the impression, in the right light conditions, of an old TV picture.

Beyond Old Square, on the south-east side are the former (Birmingham) Gazette Buildings. Built as lawyers' chambers in Italianate style in 1886 and the adjacent Crown Inn in a French style completed two years later. On the opposite side of the street stands Pitman Chambers, a good Arts & Crafts building in blue brick which is Grade II* Listed. Designed by J Crouch & E Butler in 1896, a buff terracotta frieze by the Birmingham sculptor, Benjamin Creswick, runs across the below the first-floor windows and depicts carpenters at work and diners being served at table. The building was commissioned by the furniture shop of A R Dean and by Pitman's Vegetarian Hotel & Restaurant. Above the main gable Creswick placed a free-standing group of three allegorical figures: the central female represents the City of Birmingham and holds one hand aloft, though whatever she was holding is now missing; the flanking male figure is similar to that shown on the City's coat-of-arms and formerly held a hammer now also missing; the flanking female, who represents industry, holds a distaff and stands before a spinning wheel.

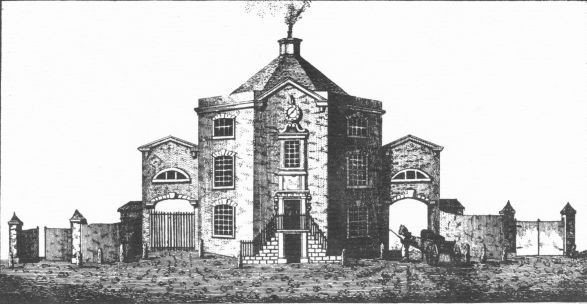

On the site of the Pitman Chambers stood the first Birmingham Workhouse. This remained until the new workhouse in Winson Green was opened on the Dudley Road in 1852. William Hutton wrote of the Workhouse in 1783:

Though the poor were nursed by parochial law, yet workhouses did not become general 'till 1730: that of Birmingham was erected in 1733, at the expence of 1173l. 3s. 5d. and which, the stranger would rather suppose, was the residence of a gentleman, than that of four hundred paupers. The left wing, called the infirmary, was added in 1766, at the charge of 400l. and the right, a place for labour, in 1779, at the expence of 700l. more.

On the corner of Newton Street is the Grade II Listed County Court designed by James Williamson in 1882, two storeys in stone in a neo-classical renaissance-palace style. Built five years before the Victoria Law Courts, its simplicity contrasts remarkably with its large flamboyant neighbour.

The Victoria Law Courts were designed by the London architects, Aston Webb & E Ingress Bell in competition with 133 other designs. It was the first major public building in Britain to have a frontage faced entirely with red terracotta and was built by the Balsall Heath firm of John Bowen. Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone in 1887 during her nationwide Jubilee tour and the building was opened 1891 by the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII. On the same site were magistrates' courts and adjacent at the rear is Steelhouse Lane police station, still in use. The use of red terracotta on such a prestigious building much boosted the use of the material as a local style, a material particularly suitable to the industrial as its very hard nature was a good defence against the polluted city atmosphere.

The building is almost symmetrical with a central porch flanked by gothic towers, two storeys and gables and a high-pitched roof; it is in eclectic late 19th-century gothic with a great deal of intricate Arts & Crafts detail. Webb described the style as French Francois I and he considered it to be his best work. Above the entrance porch is a statue of Queen Victoria by London sculptor Harry Bates; the Queen is seated in full royal regalia beneath an elaborate canopy and is intended be the personification of Justice. Beneath is a statue of St George killing the dragon, and around her are personifications of Patience, Mercy, Truth and Temperance to the designs of Walter Crane. Higher up flanking the clock are reliefs of Time and Eternity; in the gables are figures representing Art, Modelling, Design, Craft, Gun-making, Pottery.

The central gable has the royal coat-of-arms and above a traditional free-standing figure of Justice by Frith, blindfolded and holding scales. It is a building of the most intricate detail. The great hall with its timber-framed roof is of sandy terracotta and has stained glass by Walter Lonsdale showing scenes of Birmingham's history and industry. This is a Grade I Listed building within Steelhouse Lane Conservation Area and with the Methodist Central Hall forms part of a nationally important group of Victorian terracotta buildings.

A 1960s block of shops and offices replaced the 19th-century buildings between Union Street and Priory Queensway. Part of this was redeveloped in 2001 and there are proposals to redevelop the

remainder. Corporation Street will change yet again. In 1888 Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham looked forward to the street's completion:

When Corporation Street is finished, and its pathways nicely shaded with green-leaved trees, it will doubtless be not only the chief business street of the town, but also the most popular promenade. At present the gay votaries of dress and fashion principally honour New Street, especially on Saturday mornings. Hagley Road, on Sunday evenings, is particularly affected by some as their favourite promenade.

A Gallery of buildings in Corporation Street from south to north. Click on the images to enlarge them.

A contemporary glimpse of the City Centre in the 1930s is provided by Louis MacNeice, a young lecturer at Birmingham University, his first appointment after studying classics at Oxford. Belfast-born MacNeice had been writing poetry while studying at Oxford, but considered his first real poems to be those of his first published collection of 1935. He believed the first purpose of poetry was to be honest and wrote of the 1930s as a 'low, dishonest decade'. It is easy to imagine MacNeice composing his poem, Birmingham, at the corner of New Street and Corporation Street:

Birmingham Louis MacNeice

Smoke from the train-gulf hid by hoardings blunders upward, the brakes of cars

Pipe as the policeman pivoting round raises his flat hand, bars

With his figure of a monolith Pharaoh the queue of fidgety machines

(Chromium dogs on the bonnet, faces behind the triplex screens).

Behind him the streets run away between the proud glass of shops,

Cubical scent-bottles artificial legs arctic foxes and electric mops,

But beyond this centre the slumward vista thins like a diagram:

There, unvisited, are Vulcan's forges who doesn't care a tinker's damn.

Splayed outwards through the suburbs houses, houses for rest

Seducingly rigged by the builder, half-timbered houses with lips pressed

So tightly and eyes staring at the traffic through bleary haws

And only a six-inch grip of the racing earth in their concrete claws;

In these houses men as in a dream pursue the Platonic Forms

With wireless and cairn terriers and gadgets approximating to the fickle norms

And endeavour to find God and score one over the neighbour

By climbing tentatively upward on jerry-built beauty and sweated labour.

The lunch hour: the shops empty, the shopgirls' faces relax

Diaphanous as green glass, empty as old almanacs

As incoherent with ticketed gewgaws tiered behind their heads

As the Burne-Jones windows in St. Philip's broken by crawling leads;

Insipid colour, patches of emotion, Saturday thrills

(This theatre is sprayed with 'June') - the gutter take our old playbills,

Next week-end it is likely in the heart's funfair we shall pull

Strong enough on the handle to get back our money; or at any rate it is possible.

On shining lines the trams like vast sarcophagi move

Into the sky, plum after sunset, merging to duck's egg, barred with mauve

Zeppelin clouds, and Pentecost-like the cars' headlights bud

Out from sideroads and the traffic signals, creme-de-menthe or bull's blood,

Tell one to stop, the engine gently breathing, or to go on

To where like black pipes of organs in the frayed and fading zone

Of the West the factory chimneys on sullen sentry will all night wait

To call, in the harsh morning, sleep-stupid faces through the daily gate.

Above left: The former headquarters of the Midland Bank, now Waterstones's book shop, New Street at the junction with Stephenson Street.

Above right: Midland Bank doorway. My thanks for the use of this photograph to Shutterspy of Birmingham Daily photo blogspot. This image is ‘All Rights Reserved'.

Back to the walk up New Street - Upper New Street

On the north side after Corporation Street is the former Daily Post building designed in 1864 for John Feeney by the architect of the Council House, Yeoville Thomason. These were the offices and printing works of the newspaper which moved to a purpose-built block at Colmore Circus in 1960. In 1997 the whole block between New Street, Corporation Street, Fore St and Cannon Street was rebuilt the exisiting facades.

Opposite is the former Midland Hotel, now the Burlington, built in 1875 to cash in on the booming railway trade. Cannon Street retains some 19th buildings which replaced the previous generation

of 18th houses. When the street was cut by the Guest family through their cherry orchard in 1733, most of this end of New Street was still rural. Newton Chambers 43 Cannon Street and 41-42a New

Street is a buff-terracotta office block with shops by Essex, Goodman and Nicol 1899. This was the Kardomah, an Art & Crafts coffee house which still contains murals and decorative tiles and

which was refurbished in 1998.

Needless Alley itself retains evidence of an agricultural past. It takes the shape of an elongated reverses letter S and was very likely a fordrough, a farm track between the medieval fields. The

S shape is caused by the way the plough-team swung round near the end of the field to make the turn. It is a common medieval field feature.

Eliezer Edwards was a journalist on the Birmingham Daily Mail. In 1877 he collected a series of his newspaper articles and published them as Personal Recollections of Birmingham

& Birmingham Men. Here he describes how the vestiges of rural past impinged on the contemporary development of Birmingham.

Between Needless Alley and the house now occupied by Messrs. Reece and Harris, as offices, were three old-fashioned and rather dingy looking shops, of which the late Mr. Samuel Haines

acquired the lease of these three houses, which had a few years to run. The freehold belonged to the Grammar School.

Mr. Haines proposed to Messrs. Whateley, the solicitors for the school, that the old lease should be cancelled; that they should grant him a fresh one at a greatly increased rental; and that he

should pull down the old places and erect good and substantial houses on the site.

This was agreed to; but when the details came to be settled, some dispute arose, and the negotiations were near going off. Mr. Haines, however, one day happened to go over the original lease

- nearly a hundred years old - to see what the covenants were, and he found that he was bound to deliver up the plot of land in question to the school, somewhere, I think, about 1860 to 1865,

'well cropped with potatoes.' This discovery removed the difficulty, the lease was granted, and the potato-garden is the site of the fine pile known as Brunswick Buildings.

A walk up New Street - Temple Street and Birmingham Cathedral

Contemporary with Cannon Street, Temple Street was laid out before 1731 on agricultural land to take advantage of the expanding town. Local landowners, William Inge and Elizabeth Phillips had

already sold the land on which to build St Philip's Church which would be an attraction to the well-to-do to buy houses on their new estate. None of these now survive and the street is made up of

mid-19th-century, early and late 20th-century buildings. 18th Birmingham was far from the city crowded with buildings we know now. These were houses with large gardens on the edge of the open

countryside. Robert Dent wrote of an advert he had found in Birmingham's Gazette newspaper promoting the sale of a house in Temple Street in 1743:

To be Sold and entered upon at Lady-day next, a Large Messuage or Dwelling House, situate in Temple-Street, Birmingham, in the Possession of Mr. Charles Magenis, containing twelve Yards in the Front, four Booms on a Floor, sashed and fronted both to the street and Garden, good Cellaring and Vaults, Brew-house and Stable with, an entire Garden walled, and the walls covered with Fruit Trees, the Garden 12 Yards wide, and 50 Yards long from the Front of the House, and extending 22 yards wide for 26 Yards further, together with a pleasant Terrace Walk, and Summer-House with Sash'd Windows and Sash'd Doors, adjoining to the open Fields, and commanding a Prospect of four Miles Distance, and all necessary conveniences.

Likewise another House in the same Street in the tenure of Mr. George Orton, with large Shops, Gardens, and Summer-House, pleasantly situated, commanding a good Prospect; and set at nine Pounds

and ten shillings per annum.

Robert K Dent 1894 The Making of Birmingham

At the top of Temple Street stands St Philip's Church, Birmingham Cathedral since 1905. Designed by Thomas Archer of Umberslade Hall and built between 1711 and 1725, this is one of only a few churches in the English baroque style. It was built in brick but faced with sandstone from Archer's own quarries. At the suggestion of Sir Richard Gough, King George I donated £600 to complete the tower in 1725. The gilded boar's head weathervane derives from the Gough family crest in recognition of Gough's efforts to get the tower completed. At the time of its building the church was surrounded to the north and west and east by fields and orchards. These would soon make way for the elegant town houses of the wealthy were moving from the lower part of the industrial town.

William Hutton, in his 1783 History of Birmingham, wrote of his first impression of the church when he arrived in Birmingham:

When I first saw St. Philip's, in the year 1741, at a proper distance, uncrowded with houses, for there were none to the north, New-hall excepted, untarnished with smoke, and illuminated by a

western sun, I was delighted with its appearance, and thought it then, what I do now, and what others will in future, the pride of the place.

If we assemble the beauties of the edifice, which cover a rood of ground; the spacious area of the church-yard, occupying four acres; ornamented with walks in great perfection; shaded with trees

in double and treble ranks; and surrounded with buildings in elegant taste: perhaps its equal cannot be found in the British dominions.

The Umberslade sandstone ashlar did not weather well and the church was refaced in 1869 with sandstone from Hollington in Staffordshire by the Birmingham architect J A Chatwin, the tower being

completed by P B & A B Chatwin in 1958. In 1884 the church was enlarged by Chatwin and by the extending the chancel in anticipation of its becoming a cathedral. The extensions were carried

out in the original neo-classical style. The original shallow apse was replaced by a full chancel and Archer's full-height pilasters were continued by Chatwin with free-standing Corinthian

columns.

A number of memorials inside are worthy of note, including work by Peter Hollins and Williams Hollins. The state flag of Maryland USA was presented 1922 to commemorate the work done in that state

by Dr Thomas Bray of Sheldon founder of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Of especial importance are the magnificent east and west stained-glass windows by William Morris from

designs by Edward Burne-Jones: the Ascension 1884, the Nativity and the Crucifixion 1887, and the Last Judgement 1897.

A small bell was cast for the new church by Joseph Smith of Edgbaston and probably hung in a temporary belfry until the tower was finished in 1725; a second was bought that same year. Two years later Smith was given an order to build a frame for eight bells. By 1750 there were ten bells all by the same bellfounder, but at that date some were unringable and the ring was out-of-tune. The churchwardens ordered a new set from Thomas Lester of London. Three of these were recast in the following years.

In 1893 James Barwell of Hockley refurbished and rehung the bells in the existing frame and bellringing was revived in the tower until the City Surveyor judged them to be unsafe in 1906. The bells were rung occasionally during the years following but were considered to be out of tune.

The bells were recast by Gillett & Johnston of Croyden as a 12 in 1937 ready for the Coronation of King George VI and hung in a new cast iron bell frame with an additional frame above. Work on the frame was carried out by Taylor's of Loughborough in 1985 and the Whitechapel foundry refurbished and rehung the bells in 2004. With a ring of 12 whose tenor weighs over 31 cwt (Only St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring has a heavier bell), St Philip's is one of the country's premier ringing towers.

The churchyard was formerly enclosed by walls and railings with several entrance gates. Believed to hold some 60 000 bodies, it was closed to all but family burials in 1859 and laid out as a garden in 1910. When the grounds were again relaid in 2001, the railings were replaced.

Most of the upright gravestones have been removed from the churchyard to open it up as a public open space. However some monuments remain. A bronze statue at the west end made by Stirling Lee in

1914 depicts the first Bishop of Birmingham, Bishop Gore 1905-1911 and was raised during Gore's lifetime. A stone obelisk with a relief portrait commemorates Frederick G Burnaby who was killed

while attempting to rescue General Gordon in 1882; a plain marble obelisk is a monument by Peter Hollins to Lt Col Thomas Unett who was killed in 1855 at the Battle of Sebastopol; a memorial to

John Heap aged 88 and William Badger killed during Town Hall construction 1833 is the base of a column made by them and which crushed them to death when a pulley block broke. The iron Angel

Fountain set on a stone screen beneath a neo-classical pediment made c1850 was transferred from the front of Christ Church, New Street on its demolition in 1899. It was restored 1988 and is

inscribed with words of Jesus:

Whosever drinketh of this water shall thirst again but whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give shall never thirst.

The church became the cathedral of the new diocese of Birmingham 1905. It is the smallest cathedral in England and the only cathedral in the country built in the English Baroque style. It is a Grade I Listed building.

A walk up New Street - Bennetts Hill

On the south side of New Street the Piccadilly Arcade owes the slope of the footway through it to the fact that it was built as a cinema in 1910, the screen being at the Stephenson Street end. The building is in Baroque style with a large round arch across the first and second floors. The cinema closed in 1926 and was converted into a shopping arcade which was refurbished in 1989. The ceiling is decorated with intriguing trompe l'oeil paintings by Paul Maxfield.

Opposite, in contrast, is the plain 10-storey Woolworth Building of 1961 and 1964, its frontage much enlivened by the addition of a protruding glass lift in 1990. It stands on the site of the Birmingham Theatre, later the Theatre Royal.

On the west corner of Bennetts Hill is Grosvenor House, one of the first buildings to be built in the City Centre after the Second World War. Completed in 1953 the front of this unusual building

is zig-zag in profile with zig-zag projections above and below each row of windows.

Bennetts Hill was part of the estate of the related Inge and Phillips families. Bennetts Hill Close was one of a number of fields which were let in 1698 on the condition that they remain farmland

for 120 years. As the leases expired in 1818 building began at the New Street end of the estate. Bennetts Hill developments began in the early 1820s with a variety of elegant town houses, banks

and commercial premises.

Some of the earliest buildings here survive: Nos.1-5 are 2-bay early Victorian houses in a plain neo-classical style probably by Charles Edge and are Grade II Listed, No.6 is a symmetrical 5-bay house and is a Grade II* Listed building. These are rare residential survivals in the City Centre and were probably designed with shops on the ground floor. While the facades have been retained, most were rebuilt internally during the late 20th-century. Bennetts Hill is part of the Colmore Row Conservation Area. Nos. 11-12 are the site of the home of artist Edward Burne-Jones; a Birmingham Civic Society plaque marks the spot.

At the junction with Waterloo Street are two handsome bank buildings. On the west side is the former National Provincial Bank of 1870, now a wine bar. The earlier bank of 1833 was rebuilt in a neo-classical style by John Gibson in 1869, as can be seen inscribed on a frieze across the top of the building. The free-standing coat-of-arms with its male and female supporters representing the arts and industry above the main entrance by Samuel Lynn is based on the arms of the city, but before the arms were officially granted. There are carved stone reliefs in the semi-domed porch with a coffered ceiling are also by Lynn which represent Birmingham industries - metal working, metal plating, glass blowing and gun making. The bank is designed following the Corinthian order, with semi-circular-headed windows and symbolises the strength of Birmingham banking in the 19th century. The bank was extended in 1890 and in 1927 along Waterloo Street and Bennetts Hill respectively. The interior was refurbished by C E Bateman in 1927 in a subdued neo-Greco/ Egyptian/ Art Deco style.

On the south-east side of the corner is the Birmingham Banking Company building, until recently a Midland, later HSBC bank. Designed by the Rickman & Hutchinson partnership in 1830, this was

the Birmingham Banking Company's headquarters. It is a neo-classical building whose two ranges of free-standing columns with Corinthian capitals may be modelled on the temple of Vesta at Tivoli.

Yeoville Thomason extended the building round the corner in 1868 and built the new entrance flanked by Corinthian pilasters.

Click to enlarge the images in the Bennetts Hill Gallery below.

Back to the walk up New Street

88-90 New Street on the corner of Ethel Street was built as a masonic hall in 1869 by Edward Holmes, his classical design being the winner of a competition. The building was converted in to one

of the early cinema in 1908 as the the Theatre de Luxe. It was bought by the ABC chain in the 1920s and completely refitted in 1930 to hold an audience of over 1200. Renamed the ABC New Street in

1961, the cinema closed showing the film, ET in 1983.

On the opposite side is the former 10-bay Lyons Corner House of 1927 and the former Royal Birmingham Society of Artists building by Rickman & Hutchinson in 1820. The Birmingham Society of

Artists, one of the oldest art societies in the country, was founded in Peck Lane, now the site of New Street Station 1809, having developed out of local artist, Samuel Lines Academy of 1807. It

moved in 1814 to Union Street, and to the Panorama in New Street 1821. This was a circular building where very large circular panoramic paintings were displayed. It is from this date that the

society took the title of the Birmingham Society of Artists. The building was designed by Rickman & & Hutchinson in 1829 with a Corinthian portico projecting over the pavement. Queen

Victoria patronised the society 1868 when it became the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists RBSA.

During the later 19th century the RBSA exhibitions were considered second only to those of the Royal Academy. The RBSA played an important part in the Pre-Raphaelite movement; John Everett Millais, Edward Burne-Jones, Lord Leighton and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema were all presidents of the Society. Rickman's building was demolished in 1913 and the new one rebuilt with a small first-floor gallery to a faience design of Couch & Butler. The society moved to new premises in 1999 at Dakota House at Brook Street, St Pauls Square in the Jewellery Quarter 1999. The society moved to in St Paul's Square near the Jewellery Quarter c2000.

Click to enlarge the images below.

A walk up New Street - Victoria Square

Victoria Square marks the end of New Street, but our walk through the City Centre continues a little further through Victoria Square, Chamberlain Square and into Centenary Square on Broad Street.

Victoria Square, the heart of the civic centre of Birmingham, is now the place from which distances to the city are measured. First into view on the approach from New Street is a statue known as

The Iron Man by Antony Gormley. Cast in Willenhall in 1993 and paid for by the Trustee Savings Bank which then occupied the former General Post Office headquarters, the statue represents

the metal-bashing skills of Birmingham and the Black Country.

Worth a look - The General Post Office was designed by Sir Henry Tanner in French Renaissance chateau style 1890; it has steeply pitched roofs, chimneys and urns on top of little cupolas. Its

threatened demolition in the early 1970s led to a successful campaign by the Victorian Society in Birmingham to save it and subsequently to preserve the Victorian heritage of the city. It was

refurbished and the stonework cleaned by Trustee Savings Bank as their head office c1990. The bank relocated to Bristol but a Post Office counter still remains in the building, which is Grade II

Listed.

Christ Church Passage betrays the former location of Christ Church, now demolished. It was built in 1805 by public subscription to alleviate the shortage of free seats in the town - seats in most churches at that time were rented, leased or even held freehold. All the ground-floor seats were free with only the galleries reserved for rent. Known as the Free Church, this was one of only a few Birmingham churches in neo-classical style.

The body of the church being free to all description of persons, is fitted up with benches for their accommodation; but rent being paid to the clergyman for kneelings in the galleries, they are finished in a style of elegance, with mahogany, supported by light pillars of the doric order. . . .

The ascent to the galleries is by a double geometrical staircase, of stone, with ballustrades of iron, coated with brass, which appear light and produces an elegant effect; these, with the railing at the altar, were an entire new manufacture, invented by Mr. B. Cooke, whose manufactory is carried on at Baskerville House. The altar piece, designed by Mr. Stock, of Bristol, is of mahogany, above which is a painting by Mr. Barber, representing a cross, apparently in the clouds. . . . The portico and spire were both of them erected by Mr. Richardson, of Handsworth; the former at the expense of £1200 and the latter £1500, which was completed in 1816. In the year 1817, a clock was affixed in the tower, by Mr. Allport, which has four dials, and each of them both hour and minute hands. This place of worship is computed to accommodate 1500 hearers.

The erection of this free church confers great credit on the town, as the want of such accommodation was very apparent, from the increased population; and this is manifest by its being so

well attended; the congregation being considerably more numerous than can be accommodated, and they express their satisfaction by decent and orderly behaviour.

Charles Pye A Description of Modern Birmingham Whereunto Are Annexed Observations Made during an Excursion Round the Town, in the Summer of 1818

When first opened time it was much admired, though men and women sat separately in its early days, leading some wit to pen the following:

Our churches and chapels we generally find

Are the places where men to the women are joined;

But at Christ Church, it seems, they are more cruelhearted,

For men and their wives go there and get parted.

Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham 1888

The church building was not much loved in its later years, when the Gothic style held sway for church architecture. Eliezer Edwards described it in 1877 as ‘the excrescence called Christ Church,

which still disfigures the very finest site in the whole town.' Closed in 1897 and demolished two years later, the proceeds from the sale helped to fund the building of St Agatha's Church in

Sparkbrook. Burials from the catacombs beneath were church were transferred to the Church of England Cemetery catacombs in Warstone Lane, including the remains of John Baskerville. The Angel

Fountain of 1850 was moved to St Philip's Cathedral.

Well worth a look - The Town Hall

A competition was announced in 1830 to design Birmingham Town Hall, largely to house the music festivals which had been originally organised from 1768 to raise funds for Dr Ash's General Hospital

in Summer Lane. They had been held triennially from 1778 at various locations (The festivals continued until the outbreak of World War 1 in 1918.) The choice of site reflected a significant move

away from the crowded Bull Ring area, the traditional centre of Birmingham to the high town near St Philip's church. The plans of Charles Barry and Thomas Rickman, architects of great local and

national renown were rejected in favour of a plan by the young partnership of J A Hansom (later of Hansom cab fame) & E Welch. The tender submitted proved to be too low and the architects,

who were standing surety for the builder, went bankrupt in 1834. Local architect Charles Edge was commissioned to finish the hall, but due to financial constraints only completed it 1861. Hansom

is commemorated here by a Birmingham Civic Society blue plaque.

It is a building from the end of the Classical Revival and allegedly a copy of the Temple of Castor & Pollux in the Forum of Rome; standing on large rough-cut stones it is built of brick

faced with Anglesey stone. The front entrance has eight fluted columns, the sides fifteen; the original plan intended only thirteen, but Edge extended it to include the organ recess. At St

Philip's Cathedral is the memorial to John Heap and William Badger killed during Town Hall construction in 1833; it is the base of the column which crushed them when a pulley block failed.

Internally there is one large Georgian-type assembly room which was altered in 1926 to accommodate greater numbers. The first triennial music festival was held here in 1834 although the building

was not then finished. Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto in D Minor was written for the 1837 festival, his Elijah was premiered here conducted by the composer in 1846, as was Elgar's The Dream of

Gerontius 1900 (Elgar was Professor of Music at Birmingham University). The organ is by William Hill of London 1850 and has over 4000 pipes, the longest over 10 metres long.

The Town Hall was the home of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra from 1920 until 1991 when it transferred to the newly built Symphony Hall. It has also been used as a venue for a wide

variety of events: political meetings (Lloyd George escaped rioting 1901 disguised as a policeman), youth rallies (eg. Boys Brigade), music concerts (Ravi Shankar), schools drama and music, and

pop groups (eg. The Jackson Five, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Steeleye Span). The inside was used as London's Royal Albert Hall in Mark Herman's 1996 film Brassed Off. This Grade I Listed

building was closed in 1998 for refurbishment and reopened in 2007.

Click to enlarge the images in the Gallery below.

A walk up New Street - Victoria Square continued

Victoria Square has been redesigned on a number of occasions, most recently in 1993. The focal point is Indian artist, Dhruva Mistry's The River and Her Companions, a large water feature in front of the Council House. A wide paved area in front of the main entrance is the location of the upper pool on whose rim is carved is a mysterious quotation from the first of T S Eliot's Four Quartets 1935 (Burnt Norton I). Seated in a sandstone shell in the upper pool is a massive female figure in bronze weighing almost 2 tonnes, The River, representing the life force and nicknamed by the press as the The Floozie in the Jacuzzi, holds in her hands a ball from which the water sprays. The fountain is one of the largest in Europe and has a flow of 15 000 litres a minute. Water cascades down a series of steps to the lower pool where Mistry's sculpture of Youth has two smaller figures of a boy and a girl. Pedestrian steps lead down either side of the cascade; on the other side of the steps stand The Guardians, two sphinx-like animals made from the same Darley Dale stone as the Council House and symbolic protectors of the square. The work is completed with two abstract pillars with lamps, Object Variations.

The commission to design Birmingham's Council House was won in open competition by H R Yeoville Thomason with a neo-classical design despite strong support for Martin & Chamberlain's gothic entry. The foundation stone was laid 1874 by Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Mayor, and can be found near the front left-hand side of the building; construction took five years. This is a grand building in the neo-classical renaissance style of a Venetian palace designed to complement the Town Hall; a central portico faces Victoria Square flanked by classical columns, a balcony and pediment with Salviati's Venetian-style mosaic depicting personifications of Art, Commerce, Industry, Law, Liberty, Municipality, Science (Salviati was also responsible for London's Albert Memorial mosaic.). The five pediments are filled with an important series of stone carvings containing many figures, the tallest 8 metres high, designed by Thomason and carried out by Richard Lockwood, Bowton & Sons. They depict Britannia Rewarding the Manufacturers of Birmingham, Allegories of Manufacture, the Union of the Arts and Sciences, Literature, Commerce. The personifications are classically attired while the Birmingham figures are in contemporary dress.

Inside the grand staircase leads up under the dome to reception rooms and to the semicircular council chamber. In the entrance hall stands a bronze bust of the industrialist/ philanthropist/

social reformer, John Skirrow Wright who died in the Council House in 1880, a 1956 copy by William Bloye of the original 1883 statue which stood in front of the Council House and which was

subsequently destroyed. On the stairs stands a statue by John Foley 1866 of Prince Albert in Order of the Garter attire paid for by public subscription. This stood in the Art Gallery in the old

Central Library and has some discolouration caused by the 1879 fire; it was transferred to its present site in 1890. A statue by Thomas Woolner 1884 of a young Queen Victoria simply dressed, but

wearing a tiara, was paid for by money left over from the Prince Albert fund and begun by John Foley who died before its completion. On their visit in 1909 to Birmingham University, an ornate

lift was installed in the entrance hall for King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra which they reputedly refused to use; it is rarely used even now.

The Council House Clock is known as Big Brum and was installed in 1885 in a tall square tower with a pyramidal roof. The clock and bells made by Gillett & Johnstone of

Croydon were given to the city by Abraham Follett Osler. The hour bell weighs over 3 tonnes. The clock faces were originally lit by gas, but from 1937 by electric light.

A walk up New Street - A diversion along Colmore Row

Colmore Row runs from Victoria Square across the north side of the town. Some of it was built on for high- status housing from the early 1700s, but it was not fully developed until 1746 when the Colmore estate was let for building. Much of that estate was redeveloped as commercial properties when the leases expired some hundred years later. The Inge estate was developed around Bennetts Hill from 1823, initially for housing but by the end of that century many of the buildings were business premises.

Much of the eastern end of Colmore Row was rebuilt in the 1960s as part of the Inner Ring Road project and there have been extensive commercial, business and retail developments around Snow Hill

and Colmore Circus in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

For a more detailed description of Colmore Row, see The Business District.

A walk up New Street - Chamberlain Square

Birmingham City Centre in 1886 looking over Chamberlain Square with the newly extended Council House and Art Gallery (in the centre), the Town Hall (the building with pillars on the right) and Christ Church between them (demolished - now Victoria Square).

The Chamberlain Memorial which is at the bottom in the centre. Centre of left margin with a rose window is the Birmingham School of Art. New Street Station and St Martin in the Bull Ring church are above the Town Hall.

St Philip's Cathedral above the square tower of the Council House. Saint Chad's Cathedral can be seen in the background in the top-left corner of the image. The gabled roof of Mason Science College occupies the lower left corner. The rounded end of the original public library occupies the lower right corner. Drawing by H W Brewer, taken from "The Graphic" 1886

Pay a visit - Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery - The first municipal art gallery opened in the Central Library in 1865 which was also made use of to display touring museum exhibitions. Donations were soon made to a permanent collection. This was moved to Aston Hall and other sites in 1878 during rebuilding work at the library. The profits of the municipal gas department soon paid for a permanent home designed by H R Yeoville Thomason to harmonise with the Council House to which it was attached.

On land originally intended for the law courts, the building comprised offices on the ground floor to the rear of the Council House with the upper floor for the art gallery and museum: this comprised only the Round Room and the present Industrial Gallery and Edwardian Tea Room. In the pediment over the main entrance is a carved allegorical group of 1884 showing the personification of Fame flanked by Painting & Architecture and Sculpture with putti; it was executed by Francis Williamson who became Queen Victoria's private sculptor. Below it is an intricate frieze made by John Roddis of Aston. The inscription 'By the gains of Industry we promote Art' is a general comment on Birmingham's industrial wealth being used towards cultural ends, but is also a direct reference to the fact that the building was effectively paid for by profits from the municipal gas company. The Museum and Art Gallery was opened in 1885 by the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.

The Council House Extension in Great Charles Street to the rear of the Museum & Art Gallery was built to provide further accommodation for council offices and for the museum. The extension is

linked to the museum on the upper floors by a bridge over Edmund Street and was designed by H V Ashley & Winton Newman in 1912 in Edwardian renaissance style has banded rustication on the

ground floor and giant pilasters on the upper floor. It was joined to the main Council House by a bridge over Edmund Street in 1919.

The museum galleries here are known as the Feeney Galleries from a bequest of local philanthropist John Feeney, founder of the Birmingham Post & Mail. Above the Great Charles Street entrance is a large relief city coat-of-arms made by William Bloye, a teacher at the Birmingham School of Art. The city's shield is flanked by two female figures representing Art and Industry (traditionally Birmingham Industry is represented by a male). There is Birmingham heraldic stained glass the window above. City Architect A G Sheppard Fidler reconstructed the Feeney Galleries in 1958 after damage by German bombs during World War II; a plaque on the stairs leading to the galleries testifies to this. The Industrial Gallery is a fine example of a High Victorian iron and glass exhibition room; it was obscured by false ceilings and used into offices and store rooms in the 1950s but restored in 1985, to celebrate the Museum's Centenary. The original galleries were re-furbished and filled with displays of Applied Art as originally intended.

Birmingham glass manufacturer Thomas Clarkson Osler realised early on that money provided by the Council would never be sufficient to establish a quality collection and set up the Public Picture Gallery Fund in 1871 with his own gift of £3000. His precedent was followed four years by Joseph Chamberlain's £1000 and Richard Tangye's £10 000 in 1881 amongst others. The Tangye family also gave their fine collection of Wedgwood china. The Natural History collection was established in 1912 and increased in 1915 by the addition of the Beale Memorial Collection of British birds mounted in natural surroundings in memory of city politician and ornithologist Charles Beale. There was also a stuffed hippopotamus and rhinoceros previously on display at Aston Hall.

The Archaeology and Textiles Gallery opened in 1933, concurrent with the introduction of a world wide antiquities collection policy. In 1945 the City Council began to pay the museum an annual sum to enable it to increase its collections; some going to augment the collection of old masters. The collection of pre-Raphaelite art is significant and includes works by Edward Burne Jones, Ford Maddox Brown, Holman Hunt, John Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, many of them donated by Birmingham businessmen and civic leaders. Joseph E Southall was a member of the Birmingham Guild of Handicraft in the early 20th century. His fresco depicting Corporation Street in 1914 is at the head of the staircase. The Gas Rates Office, The Gas Hall in Edmund Street was converted into a gallery for travelling exhibitions in 1993. The Water Hall also to the rear was similarly converted as display space for contemporary art c2001. The Museum currently has over one million visitors a year. The Council House, Council House Clock, Art Gallery & Museum and Council House Extension are all Grade II* Listed buildings.

Click to enlarge the images below.

A walk up New Street - Chamberlain Square continued

Formerly known as Ratcliffe Place, Chamberlain Square is named after Joseph Chamberlain whose memorial monument is the focus of the square. Paid for by public subscription, the Joseph Chamberlain Memorial was erected in 1880 when Chamberlain was aged 44, to commemorate his work as a Birmingham town councillor and mayor 1869-1876. It was designed by John Henry Chamberlain (no relation) in 13th-century French/ Venetian gothic style and takes the form of a 20m spire with four gabled faces and pinnacles; the arches have carved panelling by S Barfield of Leicester, mosaics of water plants by Salviati Burke of Venice and a medallion portrait of Chamberlain by the pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner. The pools were rebuilt in 1978 and the monument cleaned in 1994. It is Grade II* Listed.

On the back of the monument is inscribed:

This memorial is erected in gratitude for the public service given to this town by Joseph Chamberlain who was elected Town Councillor in November 1869, Mayor in 1873 and resigned that office in June 1876 on being returned as one of the representatives of the Borough of Birmingham in Parliament, and during whose mayoralty many great works were notably advanced, and mainly by whose ability & devotion the Gas and Water undertakings were acquired for the town, to the great and lasting benefits of the inhabitants. On the pool walls: This memorial was restored and new pools were constructed to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of the Birmingham Civic Society 1978.

Chamberlain Square became the civic centre of Victorian Birmingham, enclosed by the Town Hall, Mason College, the Liberal Club and the (old) Central Library, all of which, with the exception of the Town Hall, were demolished during the late 1960s. The Chamberlain Memorial is all that remains.

With the building the Central Library which opened in 1974, the square was redesigned and the pools around the monument removed. However, in 1978 the Birmingham Civic Society paid for them to be rebuilt in celebration of their Diamond Jubilee.

Overlooking the square on tall plinths are statues of Joseph Priestley and James Watt. The statue of Priestley by Francis Williamson 1874 was originally in carved in white marble but was recast in bronze in 1951. It shows Priestley experimenting to produce oxygen; he directs sunlight through a lens onto mercury oxide in a crucible over which he holds an inverted test tube. The statue was originally on the east side of the Town Hall and moved to its present position alongside James Watt in 1980.

The move to erect a statue of James Watt was suggested by the Institute of Mechanical Engineers and paid for by public subscription. Watt is shown with a pair of compasses and with his hand resting on a steam engine cylinder. The statue was carved in marble 1868 by Alexander Munro who is noted for his carvings on Charles Barry's Houses of Parliament.

A bronze statue of Thomas Attwood by Sioban Coppinger and Fiona Peever of 1993 sits on the steps to the rear of the Town Hall with scattered bronze pages around him. A curve of the steps up to the library forms a semi-circular amphitheatre making the square ideal for public events.

Birmingham Central Library opened in 1865; the Shakespeare Library in 1868. Also housing Birmingham Reference Library it stood in Ratcliffe Place west of and between the present library and the Town Hall. It was joined to E M Barry's Italianate Birmingham & Midland Institute BMI building of 1857 with J H Chamberlain's 1881 gothic BMI extension along Paradise Street. The library was designed by E M Barry and the commission carried out by the architectural practice of Martin & Chamberlain.

After a disastrous fire in 1879 in which some 50 000 books and many irreplaceable medieval documents were lost. Of these only the illuminated Gild Book of Knowle was saved. The library was rebuilt on the same site still to J H Chamberlain's plan and opened by John Bright MP in 1882.