Weoley, Weoley Castle, Weoley Hill

B29 - Grid reference SP021821

Welegh, Weleye: first record 1264

This placename may be a rare Anglo-Saxon reference to pre-Christian paganism. In Old English weoh leah means 'temple clearing'. Thus the name may indicate either a settlement earlier than the conversion to Christianity c650, or more likely, a late survival of the old religion.

It is, however, possible that the name derives from weg hoh leah: 'road', 'ridge', 'clearing'. The road in question would have been the Roman predecessor of the Bristol Road which ran close to the present route. A hoh was a ridge of land of a particular shape and may be translated as a 'heel' or a 'spur' of higher ground. Interestingly, the word hoh may itself have pre-Christian associations: prominent hills were certainly used as pagan religious sites. Leah is a common word for a farmed clearing in a forest area. Weoley was an Anglian settlement on the more workable soils of the Birmingham sandstone ridge. It is also possible that the first element derives from the Old English word withig, 'withy' used to denote any member of the willow family. The castle site itself lies in the valley of Stonehouse Brook which fed the wide moat, an area of wet clay land around the stream where willows would naturally have thrived.

There is evidence of earlier settlers here. In 1915 a neolithic flint scraper was found by Edmund Dendy in Weoley Park Road while he was removing turf from the field next to his garden. And there

is evidence too of the Roman Empire. In Alwold Road a coin known as an antoninianus was found, and in Castle Road a coin of Gordian III (238-244).

But it is for its castle that Weoley is best known. This large and locally important building was for hundreds of years the manor house of Northfield. It is an important Birmingham site which was certainly occupied in Anglo-Saxon times though deeper excavation is needed for proof. Extensive excavations between 1955 and 1962 revealed that a wooden building had been constructed c1100-1200 on top of an earlier (Anglo-Saxon?) earth platform; remains of horizontal and vertical weather-boarding were found.

That 12th-century building burnt down, and was rebuilt and probably moated at this time. Roger de Somery of Dudley Castle had royal licence to crenellate his manor house of Weoley in 1264. Henry III, something of a conoisseur of gothic architecture and well aware of the value of publicity, was currently redesigning his royal castle to best effect. The vogue was taken up by his nobility and gentry who were willing to pay the king for licences for their own crenellations. However, it may be that Sir Roger was given the right to crenellate as a reward for supporting the king in the Barons' Wars.

Surviving sandstone foundations of walls and six towers date from this time. As early as 1273 there was a well-stocked deer park here. Its fortunes waxed and waned but in 1531 there were 100 head of deer. At its largest extent it covered an area of well over 1000 acres/ c400 hectares, a very large park in national terms. The area of the deer park is effectively now that of the modern housing estate of Weoley Castle.

Around 1380 all previous buildings were demolished and the whole castle was rebuilt again, partly in stone. Subsequently, over the years, Weoley Castle was altered and added to.

In a survey of 1432 the manor house was described as

the Castell of Weoley with a water called the mote compassing the 1st Castell, in which is a great halle with a great chambre in the upper ende, ... a Chapell set by hitselfe in the north part of the Castell covered wit lead, and a vestre adjoining the same Chapell, ... vi turrets of stone whereof the gate at the entre of the 3d Castell is one with 6 chambres and chymies in the same.

Sir William Berkeley was a resident lord who forfeited his estates in 1485 for having Yorkist sympathies. He was a supporter of Richard III who was defeated by King Henry VII at Bosworth Field. The following year Henry VII granted the castle to Berkeley's uncle, Jasper Tudor, the Duke of Bedford, but inexplicably sold it ten days later to John, Lord Dudley. Both Dudley and Berkeley petitioned the king when Bedford's end was imminent. In 1495 the king confirmed ownership of the manor to Dudley. However, on Bedford's death that same year the king himself took possession of the manor, and on the death of Sir William Berkeley granted all rights to his son, Richard Berkeley in 1501. The latter was the last resident lord of Northfield, because under a parliamentary act of 1523 Northfield was again confirmed to Dudley. He sold the manor and castle in about 1531 to Richard Jervoise, a wealthy London mercer, who subsequently leased the castle and deer park separately.

The Jervoise family were to hold the manor in absentio for almost 300 years. It is probably at this time that the castle gradually fell into disrepair. Certainly Chancery

proceedings of Queen Elizabeth's time imply that the castle was no longer lived in. However, the site was unoccupied by the 16th century, and its buildings were in ruins by the 17th. After the

castle had fallen into ruins Weoley Castle Farm was built south of the moat partly into the stone buildings of the castle. In 1900 the island on which the castle stood was the farm's kitchen

garden. A single apple tree still survives.

William Hutton was impressed by the ruins:

Four miles west of Birmingham, in the parish of Northfield, are the small, but extensive ruins of Weoley-castle, whose appendages command a track of seventeen acres, situate in a park of eighteen hundred.

These moats usually extend from half an acre to two acres, are generally square, and the trenches from eight yards over to twenty. This is large, the walls massy; they form the allies of a garden, and the rooms, the beds; the whole display the remains of excellent workmanship. One may nearly guess at a man's consequence, even after a lapse of 500 years, by the ruins of his house.

William Hutton 1783 An History of Birmingham

Archaeological finds

This is a site that has been extensively excavated and is well evidenced. Dry ditches, grassy banks and foundations can still be seen. Many finds show a high standard of living and included products from abroad: kitchen refuse including pig and deer bones, oyster and whelk shells, as well as cow, sheep, swan, heron, chicken, pike and hedgehog bones, and a wide variety of pottery. From the 13th century iron shears, a small axe, bronze netting needle, arrows, a padlock, the mouthpiece of a wooden bagpipe, a glazed Norman pitcher and a steelyard weight. From the 14th century painted glass and floor tiles from the chapel, scissors, a bone chessman and a bronze jug as well as pewter communion cruet c1325, glassware from the East Mediterranean and fine tableware from France and Spain.

From the 15th-century keys, horse bits and spurs, tweezers, a double-row bone comb, Spanish tin-enamelled vessels, French counters and a jet die inlaid with silver. 16th-century finds include pottery from London and Nottingham, Holland and Germany. Coin finds include a John penny 1210, Henry II halfpenny 1248, Scottish penny 1298, Edward III penny 1327-70, Richard II halfpenny 1378-88, Venetian soldino 1400-1413, Henry VI groat minted in Calais 1422-1443, gold ryall Edward IV 1461-1483. The castle, a Grade II Listed Scheduled Ancient Monument, is a City museum, although the site has been closed to the public since 1995. A viewing area has recently been built and a programme of restoration work has now started from the north-east corner where the medieval garderobe or toilet was located.

What was later known as Connops Mill on Stonehouse Brook was almost certainly the Weoley Castle mill. Standing at the north end of Senneleys Park this was a corn mill from at

least the 15th century. It took its name from Benjamin Connop, miller, farmer and beer retailer here in 1873. The mill house became the Mill Inn by 1900 and was photographed externally and

internally in the 1930s, but soon afterwards all the buildings were demolished. Part of the gearing mechanism is now in the possession of the Birmingham Museum of Science and Industry.

A 20th-century housing estate

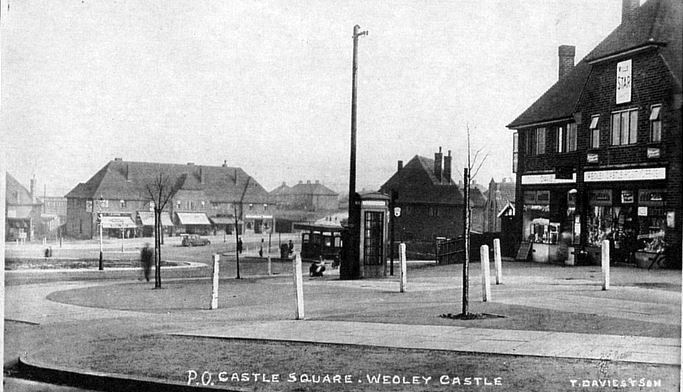

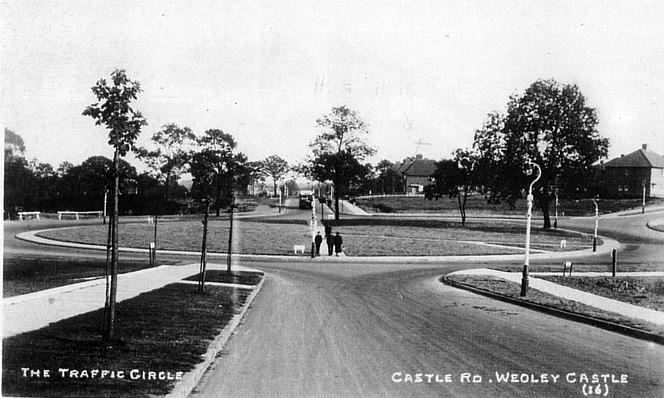

This was a rural area with no village focus until a large-scale municipal estate centred on Weoley Castle Square was laid out as something of a show estate between World Wars 1 and 2. Modelled on Bournville, almost 3000 houses were built set out with generous amounts of green and preserving many of the old trees.

Weoley Castle Square was built as a village green, a huge green roundabout, at the intersection of the estate's two main estate roads intersect as a small civic centre, with shops, banks and public buildings. However, as with many local shopping centres, this has also become the traffic hub of the district with the inevitable conflict of pedestrians and motorists. Attempts were made in 2004 to alleviate the problems.

After the Second World War the area continued to build outwards with more council housing encompassing Shenley Fields, Ley Hill and Bangham Pit.

It was at this time that St Gabriel's church was built on Shenley Lane. This is a plain rectangular building of brown brick with round-headed windows in simple romanesque style

which was consecrated in 1934.

Weoley Hill rises up from the valley of the Bourn. Around the stream has been created the Valley Parkway, a linear green corridor stretching to Bournville Park. Weoley Hill village hall, bowls club, cricket club and tennis club are on the Parkway.

After 1914 Weoley Hill Ltd was set up as a housing association to work in partnership with Bournville Village Trust to lease houses to office workers, many of whom, though not all, worked at

Cadbury's. The earliest part around Witherford Way, was built before the outbreak of World War 1. From Weoley Park Road to Middle Park Road was built from the 1920s to the outbreak of World War

2. The final part was built in the late 1950s when Cadbury's ceased sourcing milk from local farms on Cadbury land and the farmland was allocated for housing.

Our Lady & St Rose of Lima Roman Catholic Church in Gregory Avenue designed by Adrian Gilbert Scott in 1959 is a solid building said be a 20th-century interpretation of gothic. The life-size statue of St Rose on the west wall was carved by the religious sculptor, Michael Clark and depicts her traditionally, contemplating a crucifix and standing on a wreath of thorns.

The Stations of the Cross are hand-carved copies of the originals by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the father of the architect which were made for the Church of Saint Anthony of Padua, Manchester in 1904. The Angelus bell was made by Taylor's of Loughborough.

William Dargue 26.02.09/ 31.07.2010/ 18.01.2021

For 19th-century Ordnance Survey maps of Birmingham go to British History Online.

Map below reproduced from Andrew Rowbottom’s website of Old Ordnance Survey maps Popular Edition, Birmingham 1921. Click the map to link to that website.